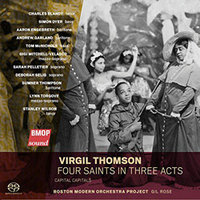

A pioneering work of avant-garde music theater—and one of the most famous collaborations ever undertaken between two Library of America authors—returns to stirring life this fall in the Boston Modern Orchestra Project’s new complete recording of Four Saints in Three Acts, the opera Virgil Thomson composed to a libretto by Gertrude Stein in 1927–8.

A succès de scandale at its February 1934 premiere at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut and an unlikely Broadway hit soon thereafter, the plotless, abstract Four Saints in Three Acts attracted a public that might not ordinarily have been expected to respond to the work of two Paris-based modernists. While the unprecedented use of an all-black cast (playing Catholic saints, no less) undoubtedly helped make the work’s name, the disarming directness of Thomson’s homespun score and the inspired whimsy of Stein’s text launched debates that regularly recur every time the work appears in a new production.

Four Saints in Three Acts continues to hover on the margins of the repertory, despite the advocacy of theater titans like Robert Wilson and Mark Morris, both of whom have staged their own productions in recent decades. The new recording offers twenty-first-century listeners a chance to hear the full work for themselves in state of the art sound; all that’s needed is a pair of ears and, just possibly, a sense of humor, all the better to appreciate such reliable earworms as “Pigeons on the grass alas” and “When this you see remember me.”

As for what the opera means, it might be wise to heed the advice Stein famously gave in a 1934 interview: “If you enjoy it, you understand it.”

Founded in 1996, the Boston Modern Orchestra Project is known for its commitment to new music and works outside the standard repertory. Via email, Library of America talked to BMOP conductor and founder Gil Rose about Four Saints in Three Acts.

LOA: Like the concert performance it’s taken from, BMOP’s new recording is making the case for Four Saints in Three Acts strictly on its musical merits—a test, in critic Jeremy Eichler’s words, of “how well the piece also holds up without any staging.” Comment?

Rose: The piece absolutely holds up without staging, because the narrative is abstracted. It’s imposed, to a certain extent, by free association in the listener’s mind based on suggestions from words, phrases, and the flavor of the music. Expressing meaning via staging is gratuitous, even limiting, in this sense—it merely shows one possible interpretation created by the stage director. But Four Saints is essentially an abstract concert work that invites the listener to form any narrative that’s meaningful to them.

LOA: Thomson’s score draws on a lot of Americana from the turn of the last century, such as Protestant hymns, folk songs, calliope tunes, marches, and waltzes. It also requires the players to make lightning-fast changes among these and other styles. How did the BMOP musicians adapt to Thomson’s idiom?

Rose: That’s absolutely right: the challenge of Thomson’s writing comes not from crazy extended techniques and flashy solos, but from the need for an intuitive sense of rhythm and style and above all, adaptability. The BMOP musicians are real pros and very versatile freelancers—they have experience in all types of music and certainly rose to the challenge. I’ll admit that I was perhaps the one most seriously challenged. Leading all those transitions clearly and effectively is no mean feat. The patchwork style is surprising, even neurotic at times. It was tough, and it kept me on my toes.

LOA: In his recent memoir Words Without Music Philip Glass writes that when he and Robert Wilson were preparing Einstein on the Beach (1976), Virgil Thomson was “then the only American composer of opera Bob and I took seriously.” Is there a line leading from Four Saints to Glass’s operas, or to other contemporary works?

Rose: I would say definitely, but as with most lines, it’s not a straight one—maybe more like a tangle of lines. There were multiple artistic movements bumping elbows through the twentieth-century American music scene. You have John Cage. You have Glass and many others seeking to simplify their musical language, whether through minimalism or other techniques. Glass’s modus operandi was based on drumming techniques. Non-Western influences were important to him, but he worked them into his version of Americana—an abstracted Americana to which he was very devoted. Thomson didn’t look to non-Western sources, but he was very interested in the American vernacular, which was folk music. So Thomson definitely did promote this idea of a shift away from traditional Western art music.

LOA: Stein’s text in Four Saints is famous for not making traditional or literal sense. Did that require special coaching or preparation for your singers? (Their diction, along with that of the chorus, is notably clear all through the recording.)

Rose: Any performance of Four Saints absolutely hinges on diction, and we worked hard at it. In any other English-language opera, you might be able to figure out an obscured word from context—not here! By the way, this was a major challenge in editing too—it messes with your ears and brain.

LOA: The new release of Four Saints follows BMOP’s earlier recording of Thomson’s Three Pictures for Orchestra and Five Songs from William Blake. Any chance his other collaboration with Stein, the opera The Mother of Us All, might be on the horizon?

Rose: So many next projects are on my wish list! The Mother of Us All is great, and so is Lord Byron—Thomson’s final opera, with a libretto by Jack Larson. Operas like these are huge undertakings, but we’re in the business of dreaming.

(For Library of America readers who want to learn more about Four Saints in Three Acts, Thomson describes the opera’s genesis at length in his 1966 autobiography, included in the recently published LOA volume The State of Music & Other Writings, while the complete libretto appears in Gertrude Stein: Writings 1903–1932.)