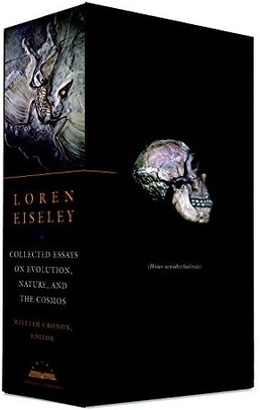

Library of America’s new two-volume set Loren Eiseley: Collected Essays on Evolution, Nature, and the Cosmos collects six books by the anthropologist, paleontologist, and teacher (1907–1977) whose writings on natural science combine the pacing of a skilled fiction writer with a poet’s sensitivity to language.

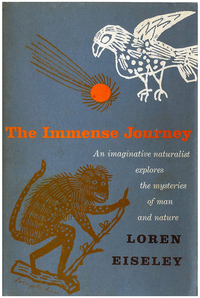

Edited by environmental historian William Cronon, the two volumes extend from Eiseley’s first collection, the unlikely million–copy best seller The Immense Journey (1957), to The Star Thrower, published posthumously in 1978.

The recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, Cronon is the Frederick Jackson Turner and Vilas Research Professor of History, Geography, and Environmental Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. His first book, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (1983), won the Francis Parkman Prize from the Society of American Historians and his second, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (1991), won the Bancroft Prize from Columbia University.

LOA: How and when did you first discover Eiseley, and what has his work meant to you?

Cronon: I first encountered Eiseley back in about eighth grade, when I somehow stumbled on The Firmament of Time and was astonished by the way he transformed my thinking about time and evolution. The passage in the final chapter in which he describes ascending a mountain and recapitulating all of evolutionary history along the way was one of the most magical pieces of prose I had ever read. I instantly sought out The Immense Journey, and from then on read every book of Eiseley’s the moment it was published. There was a period in my youth when I even aspired to write like him, and he taught me a great deal about the role of a narrator in breathing life and power into what might otherwise be a dry academic discussion.

LOA: Eiseley is often referred to as a modern Thoreau. Is that a useful comparison?

Cronon: I’m not sure it is. Eiseley was much more of an essayist and storyteller than Thoreau was. It often seems to me that Thoreau’s preferred rhetorical unit, like Emerson’s, is the sentence or at most the paragraph. He’s not really an essayist, which is why you can dip into Walden on almost any page and find something to ponder without worrying too much about taking it out of context.

Eiseley isn’t like that. He offers up extended anecdotes, usually based on his own personal or professional experience, and then weaves a complex set of essayistic questions and observations around the stories he tells. The individual parts of the essay can’t be read in isolation from each other. He also wrote very much as a scientist pondering the meaning of evolution for modern human beings, whereas Thoreau was a romantic writing before On the Origin of Species was published. Eiseley is inconceivable without Darwin.

LOA: Eiseley received effusive praise from both W. H. Auden and Ray Bradbury, two very different writers. What do you think they saw in his writing that spoke to their different sensibilities?

Cronon: Good question. You’re right that Bradbury and Auden are very different writers indeed, but they were both drawn to those numinous moments in life when what seems to be ordinary turns out to be quite extraordinary. Bradbury loved showing his readers the potential for magic (whether light or dark) just beneath the surface of seemingly unmagical things, and that is of course what Eiseley discovers over and over again in his scientific wanderings amid bones and shards and non-human creatures.

For his part, Auden was drawn less to magic than to the sacred, or at least to the possibility of seeking out sacred experience (his irony fully intact) even in a deeply fallen world. One of Eiseley’s most remarkable qualities is the almost religious intensity he brings to pondering the meaning of human consciousness and its spiritual longings in a Darwinian world where the divine can no longer be taken for granted. Auden says of Eiseley’s The Unexpected Universe that its theme is “Man the Quest Hero, the wanderer, the voyager, the seeker after adventure, knowledge, power, meaning, and righteousness…. The Quest is not of his own choosing—often, in weariness, he wishes he had never set out on it—but is enjoined upon him by his nature as a human being.” That seems to me to be precisely right about all of Eiseley’s work, and surely spoke to Auden and Bradbury both.

LOA: Like his contemporary and fellow science writer Rachel Carson, Eiseley helped shape American environmental attitudes, and his later career overlaps with the rise of the modern environmental movement. What is Eiseley’s connection to environmentalism?

Cronon: Although Eiseley was never an environmental activist, he wrote as eloquently as anyone I know about the beauty and power of the non-human world, and the profound connections between humanity and the creatures with whom we share this planet. For him, to try to understand what it means to be human without considering the long evolutionary journey of life itself would be deeply misguided. Perhaps my favorite of all of Carson’s books is her Sense of Wonder, in which she explicitly grounds her environmental values in the kinds of transformative experiences of the non-human world that are at the absolute center of Eiseley’s work. Environmentalism without wonder can all too easily lose its way.

LOA: Can we speak of an Eiseley legacy—contemporary writers who are carrying on in his tradition?

Cronon: I’m not sure. The American nature writing tradition is very rich, and has many streams and currents that lead up to the writers we read today. But there remains something sui generis about Eiseley. Because he writes so frequently of wondrous encounters that surface at the most ordinary and unexpected moments, you’d think he’d have a fair number of imitators. But what he does is a lot harder than it looks. It may actually help that he writes not as an environmentalist, but rather as someone struggling to understand the meaning of consciousness itself. How did it happen that the seemingly materialist processes of evolution conjured up a mind capable of pondering not just those processes but its own existence in a universe whose meaning it forever seeks to know? That’s Eiseley’s question.

LOA: Do you have a favorite Eiseley essay, or one you would particularly recommend to newcomers to his work? Why?

Cronon: I can’t possibly choose just one. When I read Eiseley out loud to someone who has never read him before, I often choose “The Flow of the River” from The Immense Journey, which packs a lot of punch in a very few pages. “The Innocent Fox” and “The Star Thrower” in The Unexpected Universe are extraordinary. And I cannot read his astonishing meditation on the long-ago evening in 1910 when his father showed him Halley’s Comet for the first time (in “The Star Dragon” in The Invisible Pyramid) without feeling shivers run up and down my spine. Indeed, I’m feeling them right now even as I type these words.