By Kim Morgan

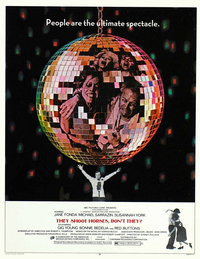

Hypnotic and surreal yet historically accurate, Sydney Pollack’s take on the Depression-era classic by Horace McCoy traps its characters, and us, inside the “macabre cabaret” of a dance marathon contest.

Horace McCoy failed his first screen test in 1931. By then, he had packed in enough life for two or three or four people. The kid from Nashville, Tennessee, had been a WWI bombardier, ambitious newspaperman, Black Mask story writer, and acclaimed stage actor. As a big shot socialite in Dallas he ditched his wife and kid to hob-nob with the well-heeled; he even ran off with a young debutante for a marriage that was quickly annulled. He wound up down and out in a dingy Dallas boarding house with a bunch of struggling bohemians. All that experience, on stage and off, that storied, heroic, hustling, sleazy life was surely imprinted on his face. But Hollywood couldn’t care less. How did he look on screen? No good? Aw, who cares about him? Who cares if an MGM talent scout had beckoned him out to Hollywood? The guy failed. Next!

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| in Crime Novels: American Noir of the 1930s and 40s |

So according to various sources, he became a vagabond, a fruit picker, a bodyguard, and a soda jerk, and eventually landed some bit parts and extra work in the pictures. He continued writing for Black Mask and finally was hired by RKO Pictures as a contract writer at $50 a week. He lied to get the job, said he had graduated from Vanderbilt University. (He was driving a taxi in Dallas during the time he’d have attended Vanderbilt. No matter. He’d lied before, he’d lie again. He needed the work.) But during all this, something significant happened. He became a bouncer for a marathon dance contest in Santa Monica. Ejecting desperate, often psychotically exhausted contestants from the depressing, mania-inducing competition—he knew he was doing them a favor. But from this soul-depleting job came the inspiration for his novel They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1935). The movie version (adapted by Robert E. Thompson and James Poe) would come much later, in 1969, but the spirit of McCoy’s own journey is all there in the screenplay, especially in a scene between the two central dance partners:

Robert: “So why California?”

Gloria: “You don’t freeze while you’re starving . . . and, there’s the movies.”

Robert: “Oh, are you an actress?”

Gloria: “I’ve done four atmosphere bits since I’ve been here. I’d a done more but I can’t get into Central Casting they got it all sewed up.”

Robert: “Don’t you know anyone who can help you?”

Gloria: “In this business, how can you tell who can help you? One day you’re an electrician; the next day you’re a producer. Any way I could ever get near a big shot is to jump on the running board of his car.”

When Sydney Pollack first stepped into New York City in 1951 his whole life changed. He’d left South Bend, Indiana, the son of a pharmacist and a troubled, alcoholic mother who died at age thirty-seven. He was eager and young, only seventeen. He had talent and charm and luck, made friends and connections easily, and he worked hard. He began studying acting with Sanford Meisner at the Neighborhood Playhouse, supplementing his income by driving a lumber truck. He served in the army for two years, until 1958, but kept his ties to the theater world, acting and teaching. He married one of his students, Claire Bradley Griswold, and they stayed married for fifty years until his death in 2008. He surely had some melancholy carried with him from his childhood, the death and instability of his mother marking him, and perhaps this is one reason he possessed empathy and an astute understanding of actors and their inner lives. He cared about politics, the world, without ever being self-important or “pretentious.” He worked on Playhouse 90 with John Frankenheimer, who was so impressed that he sent the young man to Hollywood to serve as dialogue coach for the child actors in his second picture, The Young Savages (1961). The movie starred Burt Lancaster. He noticed Pollack right away. He asked him, why are you doing this teaching? You should direct. Lancaster made a call to Lew Wasserman, sang the kid’s praises, and Pollack started directing. First television and then, by 1965, his first feature, The Slender Thread starring Sidney Poitier and Anne Bancroft. Pollack never forgot Lancaster and always, always, claimed he owed his career to him. He got lucky, he said. He was around a lot of talent and stars—ten years earlier he’d appeared on stage in The Dark is Light Enough with Katherine Cornell and Tyrone Power. That was in 1955. By 1955, Horace McCoy, age fifty-eight, was already dead.

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? was Pollack’s fourth movie. A bold choice, this grindingly sad story, a novel by a guy who never made it as far as he wanted, about two struggling Angeleno transplants, one lulled by the sea, the other by the pictures, both leaving behind their smaller lives in smaller towns only to be enclosed in one big room, the open sea outside, that big room becoming a tomb. One can only think that as an actor himself, Pollack was touched by this material, and disturbed, too. His life had fared much better. Could he have ended up like one of these poor dancing souls?

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? is a uniquely powerful movie. It’s about a time and a place (1930s Hollywood) and a specific madness (dance marathons), but its personal intensity is so traumatizing that it feels, at times, alarming. Filled with actors so perfectly cast, so agonized and raw, so vulnerable, so knowing that it’s almost too much—too hard to watch. And yet, as in McCoy’s novel, Pollack (with director of photography Philip H. Lathrop) puts us right down on the dance floor with them, following the contestants, often in long held scenes of contemplation, chatting about their lives past and present. In one especially memorable moment, a mind-cracked woman (Susannah York), fully clothed in her once-fine, Harlow-esque dress, almost seductively, but madly, tries to rub off the death that touched her gown. The story moves in the circular motion of the dance marathon, with all the drama of life on and off the floor, allowing ten-minute breaks for grateful sleep, or terrifying ice water wake-ups.

The movie often feels surreal, but it’s a historically accurate depiction of those excruciating competitions. Dance marathons began as contests in the 1920s, and quickly morphed into exploitation—despondent and grotesque freak shows. By the Depression-era 1930s, they’d become emblematic of the desperate lives many in the country were enduring. A precursor to reality shows and Survivor endurance contests, the marathons sometimes ran for over a month, with contestants falling into states of near psychosis. These were poor people, vagrants, struggling dancers, and, in Los Angeles, often struggling actors looking for their big break. Movie stars, directors, and producers, who were sometimes present at the shows, might notice these distressed dancers, and see something in them. This could be their one and only shot, some contestants thought. In McCoy’s novel director Frank Borzage is present at the horror show. In Pollack’s movie, it’s Mervyn LeRoy. But mostly regular spectators came to ogle the insanity. It was considered a base entertainment, amped up by the emcee’s continual narration, pulling out story lines and drama from couples and individuals, conflating their past and current struggles into a long-running serial. Like listening to a radio show, live and for weeks on end. How could anyone have enjoyed competing in one of these? What were people thinking as they watched this parade of human misery and madness?

In Dance of the Sleepwalkers: The Marathon Fad, Frank M. Calabria writes:

During the early morning hours, from 3 a.m. to 6 a.m., contestants went “squirrely.” Fatigue brought them to a state resembling a coma, a state which seemed to offer relief from the soreness of the day’s travail. During these episodes, contestants hallucinated, became hysterical, and had delusions of persecution. Anita O’Day vividly remembers seeing Jesus when she went squirrely. . . . In these twilight states, contestants were highly suggestible and, like the hypnotized subject of a stage demonstration, responded readily even to the most ludicrous cues. . . . If, as some dream researchers have suggested, it is the function of the nocturnal dream to allow us “to go privately crazy every night,” going squirrely appears to have had a similar function to dreaming.

McCoy witnessed this open show of dancers going crazy every night, likely with bitterness and horror, and an empathetic heart. In the novel he never looks down on his characters—they are damaged and desperate but they’re not dummies. There is nothing like this novel: experimental in form, using stream of consciousness, memory, and confession, with vivid dialogue and cinematic description, jolting readers to attention with the hard-boiled dialogue of Gloria Beatty, one of the darkest, most cynical, and at times most mordantly humorous characters in American fiction.

We know from the start what’s going to happen to this lost woman. Her death wish is stated as consistently as the dancers’ circling round and round. It’s so relentless: her hatred of the movie business, men, children, pregnant women, any kind of regular life, and just life itself:

“There’s a big director over there he didn’t introduce,” I said to Gloria. “There’s Frank Borzage. Let’s go speak to him—”

“For what?” Gloria said.

“He’s a director, isn’t he? He might help you get in pictures—”

“The hell with pictures,” Gloria said, “I wish I was dead—”

In the movie, a naïve-looking Michael Sarrazin plays Robert, the “obliging bastard” who grants Gloria (Jane Fonda) her freedom. Sarrazin, all lush-lipped, large-eyed, and hopeful, exhibits a pureness of heart, his beauty and softness working as counterpoint to what Robert will be viewed as: a murderer. A lead in other films, he never had the career that this performance promised. He famously turned down Midnight Cowboy but did appear in some interesting pictures, notably The Sweet Ride, The Flim-Flam Man opposite George C. Scott, and the under-seen and underrated Sometimes A Great Notion, directed by (and starring) Paul Newman. He’s got a lot more to him than Hollywood offered, and that intertwines with the film’s story. There’s more to Robert than most others see, too. Introduced staring at the sea, the ocean he loves (and comes to hate), he then stumbles into a Santa Monica dance hall, out of curiosity . . . it’s all chance. Unlucky chance. He meets caustic, quick-witted Gloria, and is offered to her as a switch—Master of Ceremonies Rocky (Gig Young) calls him out when Gloria’s partner isn’t allowed to enter because he’s coughing too much. Contestants can go crazy but they sure as hell can’t catch the flu.

Joining the macabre cabaret is an older sailor, Harry Kline (Red Buttons) who boasts of his vitality; a platinum blonde near-goddess—the supposedly classically trained actress Alice (a devastatingly touching York); and her dapper, distant partner Joel (Robert Fields). And then there’s the couple you worry most about, at first—James (Bruce Dern) and his pregnant wife Ruby (Bonnie Bedelia). Gloria’s always on Ruby’s case, angering her husband, James. With every scowl she seems to ask: “Why the hell is she in this thing with a baby on the way? And why the hell is she even having a baby? She can’t afford to feed it.” But Gloria doesn’t care. She is even more caustic in McCoy’s novel: “Don’t worry, I’m through wasting my breath on her. If she wants to have a deformed baby, that’s okay by me.” This is not your typical female character from 1935, let alone 1969.

McCoy initially wrote the story as a script, and his novel wasn’t a big success; only later would it come to be viewed as a classic. The best-known attempt to film it was in the 1950s, with Charlie Chaplin producing and writing, Norman Lloyd directing, Chaplin’s son Sydney as Robert, and Marilyn Monroe as Gloria. Lloyd thought Monroe would be perfect, would know Gloria down to her bitter, beautiful bones, that tough past, that hard-bitten sadness. He believed that she could be directed to deliver a performance with naturalism and grit. This project fell apart, for various reasons, and as I recently discussed with Lloyd, it has disappointed him to this day.

Lloyd confessed that he believed Monroe would have bettered Jane Fonda; that Fonda was, perhaps, too refined for this character. But as magnificent as the Chaplin/Lloyd/Monroe film version might have been, and how Monroe’s career might have moved into a significantly different direction had it been made, Jane Fonda is absolutely and unexpectedly brilliant as Gloria, a woman who has lost at life, but whose toxic view of the world is catching.

Gloria’s twin cynic is Rocky, played by Gig Young in another complicated, unexpected performance by an actor who, so far, had not shown this kind of range. This is a seedy older Gig Young (who nine years later would, in real life, murder his wife and kill himself), and as the emcee he’s the exploitative devil, the narrator of the danse macabre, spouting his “Yowza, Yowza, Yowza” as the band plays a dreary, soul-deadening tune. He shows signs of what might either be empathy or just a need to move the show along as he occasionally steps in and helps a contestant. One woman goes squirrely, screaming of bugs crawling all over her. He calms her down and gently brushes away the hallucinated insects. Gloria mockingly asks why he wouldn’t use that as a floorshow, as entertainment, and he answers grimly, “It’s too real.”

It’s too real. That is indeed what Pollack excels at here. Flesh and blood dancers turn into sleepwalking ciphers. When they slip into shorts and skimpy athletic tops, Rocky makes note of their “knees” as audiences get a gander at flesh, bobbing breasts, swaying backsides and enervated hard-ons. The more Robert and Gloria drape on each other, sweat and sleep, the more a sort of slow-moving courtship occurs. It seems every aspect of human nature is trotted out for the world to see, and here are we, the viewers, watching it too. Pollack makes us empathize to the point of punishment. It’s a grueling movie, death-obsessed, almost dangerous. We get Gloria so much that we don’t blame her.

Who is Gloria Beatty? Horace McCoy likely saw something of himself in his fractured heroine. He faced his own daily endurance test of hard living and in the end, succumbed to a heart attack. As author Robert L. Gale (Characters and Plots in the Novels of Horace McCoy) wrote, “Ill health was finally the ruinous consequence of McCoy’s self-indulging life style. Overweight and a weakening heart kept him from finishing his sixth novel. Corruption City was completed by another and published four years after his early death, ironically, in Beverly Hills—in California, that state from which he had longed to escape.” Gloria, seeking release, can’t even successfully poison herself to death (she is regretful of that) and instead, asks Robert to blow her brains out. It’s the film’s most personal moment—almost erotic. It’s their only kind of kiss, the gun to the head, both a sleep-deprived, crazy merciful gesture and a dark orgasm. You can feel the rush when he closes his eyes and does the deed. And, sadly, awfully, you can feel the love.

Pollack does not play this scene cheap—Gloria, looks up, tears streaming down her face, pleading to Robert, “Help me.” She hands over her own pistol and Robert shoots, blood sprays from her head, her body slowly jerks and collapses. A director will not walk in and give Gloria her shot. But Robert does—the final shot. The officer enquires, “Why’d you do it kid?” He answers, “She asked me to. . . . They shoot horses, don’t they?”

Watch: Original 1969 trailer for They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (3:05)

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969). Directed by Sydney Pollack. Written by Robert E. Thompson and James Poe, based on Horace McCoy’s novel. With Jane Fonda, Michael Sarrazin, Susannah York, Gig Young, and Red Buttons.

Buy the Blu-Ray • Buy the DVD

Kim Morgan has written for Sight & Sound, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Criterion Collection, Playboy, and many other publications. She was a Shorts Film Juror at Sundance, a Guest Programmer on Turner Classic Movies and the Guest Director of the 2014 Telluride Film Festival. She is a regular contributor to the blog at New Beverly Cinema. You can find her at her blog, Sunset Gun.

The Moviegoer showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.