By Steve Vineberg

Only a handful of the movie musicals adapted from Broadway live up to the legendary originals; here are three all-time classics that do, along with a runner-up that preserves a spirited stage smash with its élan intact.

With the understandable exception of the musical revue As Thousands Cheer, every selection included in the Library of America’s two-volume set of musical-theater libretti, American Musicals (edited by Laurence Maslon), has generated a movie version; one, Show Boat, has been filmed twice. Hollywood began looking to the Broadway musical stage for source material as soon as sound came in, and even after the golden age of the Hollywood musical—roughly a twenty-five-year period beginning in 1933—had faded, major stage musicals continued to be filmed as a matter of course, as roadshow attractions and usually at exorbitant expense. Some, like My Fair Lady and The Sound of Music, were very successful at the box office and won the Oscars that have so often been reserved for lavish adaptations of Broadway musicals. Others were increasingly unwelcome as the counterculture audiences of the late sixties and early seventies took over the moviehouses: they didn’t want to see Paint Your Wagon or Sweet Charity.

Of the sixteen movies adapted from the shows in the collection, only a handful live up to the legendary status of the originals. Some, like the 1949 On the Town and the 1957 Pal Joey, are so severely altered that fans of the stage musicals would scarcely recognize them. Three, however, stand among the best movie musicals ever made. And another earns our gratitude for preserving a spirited Broadway smash with its élan intact.

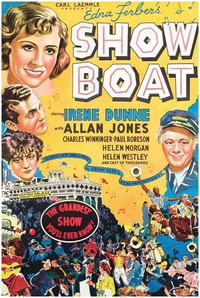

Show Boat (1936). Directed by James Whale. Screenplay by Oscar Hammerstein II, based on the play by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II, adapted from the novel by Edna Ferber. With Irene Dunne, Allan Jones, Helen Morgan, Paul Robeson, Charles Winninger, Hattie McDaniel, and Helen Westley.

Buy the DVD

James Whale, much better known for cheeky horror pictures like The Old Dark House and The Bride of Frankenstein, was Universal’s choice to helm its 1936 film of Show Boat. One might have expected a screen adaptation of what was at that point the most famous of all American musicals to land at MGM, the lushest of the studios, but Universal had made a part-talkie of the Edna Ferber novel on which the musical was based and owned the rights. And perhaps the end product was better than it would have been at MGM, which might have been tempted to make it overlong and ostentatious. (Its own big musical of 1936, the Oscar-winning The Great Ziegfeld, came in at three tedious hours.) Whale was a showman but he possessed the virtues of economy and focus, and he applies both to Show Boat, which manages, with the considerable aid of its screenplay by the original librettist, Oscar Hammerstein II, to tell a sprawling four-decade story—a romantic melodrama that begins in 1887, in the heyday of the Southern show boats—with a rolling sweep.

| BUY THE BOXED SET |

|

| American Musicals: The Complete Books and Lyrics of 16 Broadway Classics (Two volumes) $48.00 with coupon code BTS2016 through Sep. 12 |

Show Boat pioneered the Hollywood tradition of securing some of an original production’s stars to recreate their performances. In this case two members of the movie cast had appeared in the 1927 Broadway show. They are Charles Winninger, who plays Captain Andy, proprietor of the Cotton Blossom, and Helen Morgan as the gifted singer Julie La Verne, whose life falls apart after a bitter rejected suitor reveals that she’s half-black and married to a white man—illegal below the Mason-Dixon line. Though he didn’t create the role of Joe, a dockworker, the great, outsize balladeer Paul Robeson had also played it on stage. It’s hard to imagine this Show Boat without Morgan’s plaintive, warbling renditions of “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man” and “Bill” or Robeson’s rendering of “Ol’ Man River,” still the signature version of the Jerome Kern-Hammerstein tune. Morgan’s character disappears halfway through the movie, to return in only one scene, and Robeson’s is a supporting character; the hero and heroine are Captain Andy’s daughter Magnolia Hawks (Irene Dunne), who becomes a star, and Gaylord Ravenal (Allan Jones), a gambler who becomes first her leading man and then her husband. But the combination of Morgan’s performance and Robeson’s “Ol’ Man River” supply the emotional core of the movie, which is why, despite the happy ending, it feels like a tragedy. Robeson, in fact, is playing essentially a comic character, a cheerful fellow whose wife Queenie (Hattie McDaniel) complains, though with fondness, over his indolent nature. Kern and Hammerstein added a charming new duet for them, “I Still Suits Me,” and it’s one of the movie’s highlights. But the specific racial story built around Julie and the generalized one implied in “Ol’ Man River,” the lamentation of the African American in the post-Civil War South, soak the movie in sorrow. (Postscript: MGM eventually released a remake, in 1951. It was misbegotten.)

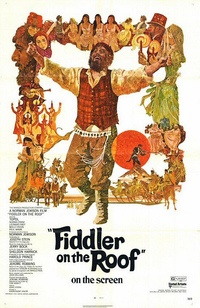

Fiddler on the Roof (1971). Directed by Norman Jewison. Screenplay by Joseph Stein, based on the play by Joseph Stein, Jerry Bock, and Sheldon Harnick, adapted from stories by Sholem Aleichem. With Chaim Topol, Norma Crane, Molly Picon, Rosalind Harris, Leonard Frey, Paul Mann, Michele Marsh, Paul Michael Glaser, and Neva Small.

Buy the Blu-Ray • Buy the DVD

Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Vudu

Fiddler on the Roof, with its beloved Jerry Bock-Sheldon Harnick score, was still playing on Broadway (where it had opened seven years earlier) when Norman Jewison’s film version came out in 1971. It’s a faithful transcription of the show, with Joseph Stein adapting his own magnificent libretto. Perhaps partly because the musical was so well known by the time the movie came out, and partly because it was a big, decidedly un-hip studio musical, it has tended to be insufficiently prized by critics and historians, even though it was a box-office triumph. Although many of its extraordinary qualities are transferred from the play—like the beautiful conception of numbers like “Tradition” and “Sabbath Prayer,” which use the conventions of the musical to channel profound cultural ideas that, “Ol’ Man River” aside, previous musicals had rarely touched on—the movie has its own widescreen exuberance. Much of its splendor is in the casting and in Jewison’s underrated direction. The role of Tevye the dairyman, whose resilience is tested on the one hand by the insistence of each of his three daughters to follow her heart and make romantic decisions that fly in the face of Jewish tradition, and on the other by the anti-Semitism that culminates in the exile of the Jews from their shtetl, had been played on Broadway by the bigger-than-life musical-comedy performer Zero Mostel. He was succeeded by Luther Adler, one of the first American actors trained in the Stanislavskian system but also the son of a famous star of the Yiddish theater. Jewison chose Topol, an Israeli stage and film performer with the authority of a great musical-theater performer and the grandeur of a great screen technician. Topol had played the part in London’s West End but was unknown to American movie audiences. So was most of the rest of the cast, like Norma Crane as Tevye’s wife, Golde, and Rosalind Harris, Michele Marsh, and Neva Small as their daughters. The movie is not exactly a de-familiarization of the musical but it’s certainly a fresh incarnation of it, with a warmth and intimacy that grounds the characters in this big-boned folk fable.

Movie musicals that are not shot on soundstages in the manner of golden-age musicals have to meet the challenge of balancing an inherently stylized genre against the implied naturalism of real landscapes. For Fiddler, which was shot in and around Zagreb, Yugoslavia, Jewison chose a cinematographer, Oswald Morris, with a long and varied career who was most recently famous for the gritty, lived-in look of English New Wave dramas like Look Back in Anger, The Entertainer, and The Pumpkin Eater. The visual results are exquisite, like broad canvases imbued with the sunlit detail of scenes by Corot or Millet. In the most memorable sequence, an inspired addendum to Stein’s text, bearded old men on rafts are carried away from Russia in luminescent long shots that imply the next chapter in the history of the Jewish diaspora. At this point Jewison’s vision attains an epic dimension and links up with another towering film from 1971, Jan Troell’s The Emigrants.

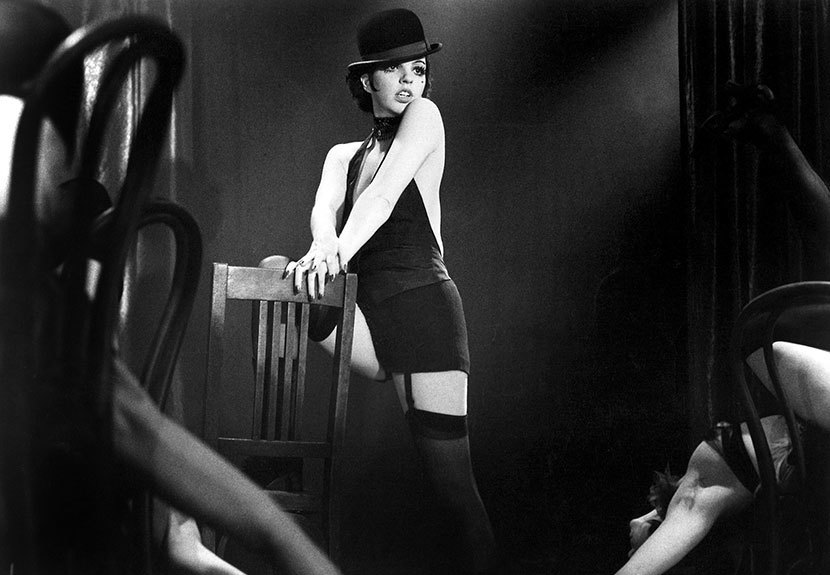

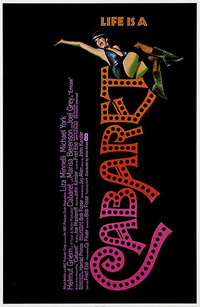

Cabaret (1972). Directed and choreographed by Bob Fosse. Screenplay by Jay Presson Allen, based on the play by Joe Masteroff, John Kander, and Fred Ebb, adapted from the play I Am a Camera by John Van Druten and stories by Christopher Isherwood. With Liza Minnelli, Michael York, Joel Grey, Marisa Berenson, Helmut Griem, and Fritz Wepper.

Buy the Blu-Ray • Buy the DVD • Watch on Amazon Video

Watch on Google Play • Watch on iTunes • Watch on Vudu

Most of the lavish film musicals made in the late sixties and early seventies were critical and box-office failures, yet the era also produced some of the most enduring ones. Bob Fosse’s Cabaret, released a mere three months after Fiddler, in February 1972, also illuminated a tragic historical epoch—Weimar-era Berlin—but its tone and style could hardly have been more different. Fosse came from the stage, and his first attempt at a movie, the 1969 Sweet Charity, felt like what it was: a transplanted Broadway musical that he’d directed and choreographed in its original form. It had spectacular dances but it lacked a cinematic concept. Cabaret also began as a musical play, though derived from a straight play adapted from some Christopher Isherwood stories. But the screenwriter, Jay Presson Allen, rewrote much of the narrative, throwing out supporting characters and substituting others, filling in the underwritten main characters, the young English writer Cliff (renamed Brian and sensitively played by Michael York) and the outrageous English cabaret singer Sally Bowles (now an American émigré played, unforgettably, by Liza Minnelli), and strengthening the political subtext. The best thing about the Broadway version of Cabaret, which Harold Prince directed, was the Brechtian cabaret numbers, most of them built around the brilliant, one-of-a-kind Joel Grey as a grinning, malevolent Master of Ceremonies. But most of the songs were in the conventional mode of “naturalistic” musicals, conveying the emotions or defining the personalities of the characters who sang them. Fosse eliminated all of those. The sole number in the movie that doesn’t take place in the Kit Kat Klub where Sally works and doesn’t provide Brechtian commentary on either the dramatic narrative or the rise of Hitler is the song in the countryside beer garden, “Tomorrow Belongs to Me”: a youth with a cherubic face and a pure tenor rouses a crowd of all ages to an increasingly fervent rendition of a Nazi anthem. Seven years earlier, Robert Wise’s film of the saccharine Rodgers and Hammerstein operetta The Sound of Music had offered one single moment of authenticity, an image of the Nazi flag waving atop a grand old Viennese mansion. The opening verse of “Tomorrow Belongs to Me”—which is, eerily, the sweetest and most melodic tune in John Kander and Fred Ebb’s score—builds on the shock effect of that image when Fosse pans down the body of the singer to reveal his swastika armband. At first only two other young men in Nazi uniforms join in, but by the end of the song almost everyone in the café is on his or her feet, swelling the chorus.

Fosse establishes the function of the cabaret performances in the opening number, “Willkommen,” which begins with an abstracted close-up of a sinuous silvery mass that, as the image grows clearer, turns out to be a distorted stage mirror reflecting the audience of the Kit Kat Klub. Some of the patrons are cardboard cutouts based on George Grosz paintings; Fosse mixes Brechtianism with expressionism. Here the Master of Ceremonies (Grey, the only alumnus of the Hal Prince production) discharges the double duty of welcoming that audience—and us—into the world of the cabaret and, by implication (that is, through the use of intercutting), welcoming Brian to Berlin. At one point the choreography even mimics the motion of the train that brought him. The worn, animated, benign-seeming faces of the men and women he passes in the street, his introduction to the inhabitants of the city, are echoed later in the faces of the beer drinkers that turn aggressive and sinister in “Tomorrow Belongs to Me.”

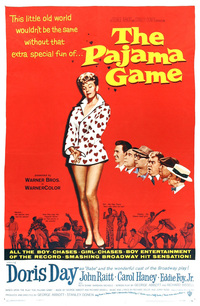

The Pajama Game (1957). Directed by Stanley Donen and George Abbott. Screenplay by George Abbott and Richard Bissell, based on the play by George Abbott, Richard Bissell, Richard Adler, and Jerry Ross, adapted from the novel 7½ Cents by Richard Bissell. With Doris Day, John Raitt, Eddie Foy Jr., Carol Haney, Reta Shaw, and Jack Straw.

Buy the DVD

One other movie version of a show in the American Musicals collection deserves a shout-out—and not only because it presents an early, vivifying sample of Bob Fosse’s choreography. The 1954 Richard Adler-Jerry Ross hit The Pajama Game was transferred to the screen three years later by George Abbott, who’d staged it on Broadway, in collaboration with the great movie-musical director Stanley Donen, with almost entirely the same cast who’d performed it on stage. The one concession to movie audiences was Doris Day, replacing Janis Paige as Babe Williams, the pajama-factory union loyalist who falls for the new superintendent (John Raitt)—and it is one of Day’s handful of good performances. She’s vibrant and a little raucous and she wears her heart on her sleeve.

In Cabaret Fosse reinvents the movie musical, as well as the show he’s transporting to the screen. In The Pajama Game he mostly replicates the numbers from the stage production. But they’re marvelous numbers (especially “Racing with the Clock” and “Steam Heat”), and Donen uses the 1.85:1 aspect ratio and WarnerColor to give movie audiences the experience most of them couldn’t get on Broadway, with a more expansive glossy, deluxe look that makes it feel unmistakably like a Saturday night movie outing. And Donen opens up the action in the “Once-a-Year Day” company-picnic number, where the wide screen allows him the expanse he needs to showcase the bounding, leapfrogging Fosse choreography, which is built on the idea of high-spirited competitive games. With its personnel imported from New York and the score only slightly pared down to accommodate a roughly two-hour running time, it’s an excellent example of a peculiar subgenre of movie musical, the (almost) straight-from-Broadway kind. Bells Are Ringing, The Music Man, and How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying are later ones; Donen and Abbott collaborated on another, Adler and Ross’s Damn Yankees, but it wasn’t as gratifying as The Pajama Game. Of the few admirable screen versions of the musicals in the two Library of America volumes, The Pajama Game is the only one not set in an earlier period, and among its other pleasures it offers a time capsule of the decade in which it was written. The Pajama Game, with its small-town Midwestern setting and its romantic story underscoring the conflict between labor and management, is perhaps the quintessential 1950s musical.

Steve Vineberg teaches theater and film at College of the Holy Cross and is a regular contributor to The Threepenny Review and Critics at Large. He is the author of three books: Method Actors: Three Generations of an American Acting Style; No Surprises, Please!: Movies in the Reagan Decade; and High Comedy in American Movies: Class and Humor from the 1920s to the Present.

The Moviegoer showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.