By Charles Taylor

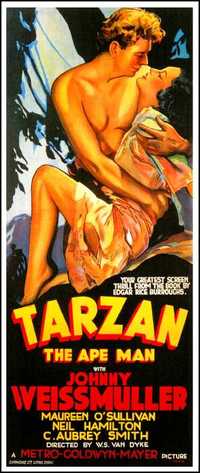

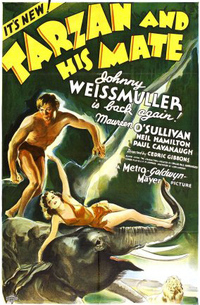

Few Hollywood movies before or since have transmitted such a feeling of lovers at play as Tarzan the Ape Man and Tarzan and His Mate—a rare cinematic portrait of a marriage that works and the version of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s novel that has taken the deepest root in the public imagination.

“Let a woman be a woman and a man be a man”—Prince, “Gett Off”

“Me Tarzan—you Jane.” Like “Play it again, Sam,” a famous line that never appears in the movie it’s credited to. Tarzan’s exercise in nomenclature has long been used to characterize the traditional model of sexual relations, the dominant man and the subservient woman, and, in the process, to mischaracterize what must be one of Hollywood’s happiest portraits of the satisfactions to be found in convention. The six Tarzan and Jane movies starring Johnny Weissmuller and Maureen O’Sullivan produced by MGM between 1932, when the series began with Tarzan the Ape Man, and 1942, when it concluded happily with Tarzan’s New York Adventure, add up to an anatomy of a creature even rarer than those with whom Tarzan and Jane share their African escarpment: a marriage that works.

That’s probably not what Edgar Rice Burroughs had in mind when he published the first of his twenty-three Tarzan books, Tarzan of the Apes, in 1914. Burroughs’s wonderful novel remains an immensely readable and satisfying piece of Edwardian adventure pulp. Tarzan’s origins, not a matter of concern at MGM, are the English aristocracy. He is in fact Lord Greystoke, born in the jungle when his parents are put ashore by the mutineers who have taken over the ship on which they are passengers. The enduring power of Burroughs’s romance has to do with this refusal to separate savagery from sentimentality. At times the novel reads something like Dickens turned red in tooth and claw, nowhere more so than in the remarkable scene following the death of Tarzan’s parents in which he, as an infant, is adopted by Kala, the great ape who, after the death of her own baby, will raise him as her own. This is how Burroughs describes Kala’s rescuing the baby from the fury of the male ape who kills Tarzan’s father and has already killed her infant:

When the king ape released the limp form which had once been John Clayton, Lord Greystoke, he turned his attention toward the little cradle, but Kala was there before him, and when he would have grasped the child she snatched it herself, and before he could intercept her she had bolted through the door and taken refuge in a high tree.As she took up the little live baby of Alice Clayton she dropped the dead body of her own into the empty cradle; for the wail of the living had answered the call of universal motherhood within her wild breast which the dead could not still.

High up among the branches of a mighty tree she hugged the shrieking infant to her bosom, and soon the instinct that was as dominant in this fierce female as it had been in the breast of his tender and beautiful mother—the instinct of mother love—reached out to the tiny man-child’s half-formed understanding, and he became quiet.

Then hunger closed the gap between them, and the son of an English lord and an English lady nursed at the breast of Kala, the great ape.

Overwritten, even flowery, that passage is an argument for why “good writing” is less important to good novels than emotional commitment and narrative verve. It also hints at a persistent strain in the first two MGM films, Tarzan the Ape Man and the glorious first sequel Tarzan and His Mate (1934): the refusal to treat the animals’ capacity for joy or anguish as less than that of human beings.

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| Edgar Rice Burroughs: Tarzan of the Apes |

Let’s get the obvious out of the way: Yes, Tarzan is a white man who has gained dominance over the wild beasts of Africa. Yes, the natives are divided between the good subservient ones ready to help the white men and the bad, bloodthirsty ones determined to turn the white interlopers into dinner or household furnishings. (Hilariously, the Pygmies who figure in the climax of Tarzan the Ape Man stage a pre-killing ceremony that looks like a dress rehearsal for the scene in Gremlins where the creatures lay blissful siege to a neighborhood movie theater during a screening of Snow White.) Yes, the movies casually show the brutality that the white hunters exercise over their black bearers. On the other hand, the white hunters are the villains. And it doesn’t take anything special in the way of brains or integrity to flaunt your moral superiority to eighty-year-old cultural artifacts.

Tarzan the Ape Man and especially Tarzan and His Mate make space for the animals to shine alongside the human cast, and in some cases, outshine them. There’s a wonderful moment in Tarzan and His Mate in which Tarzan, wounded by an evil hunter, falls unconscious beneath the surface of a lake. Seconds later, a hippo descends into the water and arises bearing Tarzan’s body across its back. It’s a quietly operatic image, a fallen hero being borne from the battlefield. In both movies, Tarzan and Jane’s chimpanzee Cheetah gets a chance to mourn an older ape who has died protecting Tarzan. The scenes are done with a sense of tact instead of a determination to squeeze the audience for tears. We see Cheetah’s usual restless curiosity become suddenly becalmed as he approaches the dead ape’s body, and we hear his little inquiring squeaks of distress. (Elsewhere, when he happily puffs on a discarded cigarette, or claims some of Jane’s scanties and parades around in drag, or when he stops to monkey with some baby leopards and narrowly escapes the angry mother, Cheetah is to the series what Harpo is to the Marx Brothers—its angelic anarchic id.)

Both movies have an ostensible plot in which the white hunters arrive to plunder the elephants’ graveyard for ivory. When, in Tarzan and His Mate, Tarzan refuses to lead them to this secret spot, Jane explains to one of the hunters that the elephants would regard such theft as a desecration, as humans would the looting of their ancestors’ graves. Predictably, the hunter finds the idea ridiculous. And he’s so determined to find the ivory that he shoots an elephant to follow the dying creature to its resting place. There’s a special horror to the moment, the utilitarian cruelty of it so much worse than the animal attacks and native rampages elsewhere in the movies. Those things are inseparable from the jungle world the movie is showing us. The hunter’s violence is a virus injected into it.

In these first two Tarzan movies, civilization, embodied by the (always English) white hunters, almost always comes off as constipated and clueless when not downright brutal. The hunters come in two varieties—dim and affable Harry Holt (Neil Hamilton, later Commissioner Gordon in Batman) in both films, and dim and venal Martin Arlington (Paul Cavanagh) in Tarzan and His Mate. These are the old-boy sorts who roam the world as if every place were just an outpost of their club, some locations featuring dreadfully substandard accommodations, but then, what can you expect of savages? It can be a drag sitting through these scenes while you wait for Weissmuller to show up—especially in the first movie, which has the same pokey pace the director, W.S. Van Dyke, brought to The Thin Man, another adaptation saved by the charm and chemistry of the leads. But tucked away beneath the surface of the films is the unspoken promise that sooner or later we are going to have the pleasure of seeing these stuffed shirts get it. That pleasure is always mitigated by putting either Jane or Tarzan in danger alongside them, almost as if, without the fate of characters we care about hanging in the balance, we would too easily be able to indulge our sadistic joy in watching the series’ various bwanas get theirs.

Nowhere do these exemplars of civilization seem more deluded about their place in the world than in their attempts to woo Jane away from Tarzan. Neil Hamilton’s Harry, lovesick and moony, arranges for his fellow hunter Arlington to bring the latest fashions on safari, believing he can lure Jane back to England. She does the requisite cooing but declares her intention of staying with Tarzan. So the joke becomes watching these two Drones Club refugees playing that game so beloved of the disappointed male suitor: What Does She See in Him? And because we in the audience can see, the answer is obvious. Johnny Weissmuller, the former Olympic gold-medal swimmer, firm and trim without having that hard muscled look, is simply one of the most beautiful men to ever step before a movie camera. Walking around in his loincloth, with what, in the ’30s, must have seemed impossibly long and unruly hair, Weissmuller is winningly unselfconscious, and a natural gentle-spirited comedian, which suits the character beautifully. (It makes you wonder what another great unselfconscious camera subject, Keanu Reeves, might have done in the role.) You take one look at him and the notion that anyone could prefer one of these Anglo weeds in their fussy little safari shorts and pith helmets becomes irresistibly absurd. And in the sun of Tarzan’s protective adoration, O’Sullivan’s Jane blooms from a somewhat precious Mayfair girl to one who retains her good manners while becoming adventurous—even sexually adventurous. That’s the unspoken implication when Jane asks her would-be suitors why she would ever leave Tarzan for any other man.

“There’s quite a difference, isn’t there?” Jane says in Tarzan the Ape Man, as Tarzan compares his huge hand with hers. “You like that difference,” she adds, and the frankly sexual tone, the way O’Sullivan lays a light emphasis on “like,” and the way she looks right at Weissmuller when she says it, is intoxicating. The first two movies benefited from being made before the censorious Production Code took effect in 1934, and few Hollywood movies before or since have transmitted such a feeling of lovers at play. That abandon is present all throughout Tarzan and His Mate (rousingly directed by Cedric Gibbons). The nude swimming scene where Weissmuller gets to show off his swimming skills and O’Sullivan is doubled by Olympic swimmer Josephine McKim may have been included solely to titillate the audience but it’s lyrical and erotic in the way that, say, ballet almost never is in the movies. In one of the movie’s wittiest touches, Jane gets her own trilling little call to match Tarzan’s bellow, and she even gets to swan dive off of tree boughs into her beloved’s waiting arms. We’re very aware of skin in this movie: Jane sleeping nude under animal skins and her and Tarzan’s naked flesh always seems to be touching. (The halter top and skirt O’Sullivan wears in Tarzan and His Mate, which allow her and Weissmuller to seem naked when they’re riding an elephant, she leaning back against him, was replaced by a demure jungle dress in later entries.)

Love and sex and marriage are, in this movie, not clashes of personalities and wills but harmonious combinations. Jane’s pleasure at having a mate who will protect her, provide for her (Tarzan wakes in the morning and goes off for fresh fruit to serve her while she’s still in bed), shelter her, and be a strong and satisfying lover doesn’t make her weak. She doesn’t protest when Tarzan is sick of company and whisks her off to their treetop bed. (Part of marriage is knowing your spouse’s temperament well enough to know when they’ve had it.) And Jane’s attempts to teach Tarzan some manners or English (including the morning greeting, “Good morning. I love you,” which he pronounces as “Goodmorning Iloveyou”) don’t emasculate him. Neither does the melting adoration in his eyes when he looks at her. (Weissmuller may not have been a trained actor, but he could transmit the ardor of devotion with indelible tenderness.)

Five actors had already played Tarzan on-screen before Weissmuller took the role, and at least fifteen would follow. Weissmuller would carry on without O’Sullivan (who reportedly became sick of playing Jane) in five more Tarzan movies when the series switched to RKO. He’d also do the Jungle Jim movies (sixteen) and TV show (one season). There would also be Tarzan comic strips, Saturday morning cartoons, TV series, a Disney animation and a Broadway musical based on the Disney version. (A new live-action version with Alexander Skarsgard and Margot Robbie, directed by David Yates, who did fine work on four Harry Potter movies, opens July 1.) But the six Weissmuller–O’Sullivan movies remain the version of Burroughs’s creation that has taken the deepest root in the public imagination.

There are too many examples of strength and vulnerability shown by both Tarzan and Jane for these films to be seen as some sort of corrective to changing sex roles. But the attractiveness of two characters who realize exactly who they are, as a couple and as individuals, resonates at a time when the possibilities of gender identity have become so vast they’re exhausting even to contemplate. Just as Tarzan does, we like the difference.

Trailer for Tarzan and His Mate (3:01)

Tarzan the Ape Man (1932). Directed by W.S. Van Dyke. Written by Cyril Hume and Ivor Novello, based on Edgar Rice Burroughs’s novel Tarzan of the Apes. With Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O’Sullivan, Neil Hamilton, C. Aubrey Smith, and Forrester Harvey.

Watch on Amazon • Watch on iTunes • Buy on DVD

Tarzan and His Mate (1934). Directed by Cedric Gibbons. Written by James Kevin McGuinness, Howard Emmett Rogers & Leon Gordon, and Bud Barsky, based on characters created by Edgar Rice Burroughs. With Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O’Sullivan, Neil Hamilton, Paul Kavanagh, and Forrester Harvey.

Watch on Amazon • Buy on DVD

Charles Taylor’s writing on movies, books, popular culture, and politics has appeared in The New York Times, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Nation, Slate, Dissent, The Village Voice, and other publications. He currently writes for The Yale Review and his book, Opening Wednesday at a Theater or Drive-In Near You: The Shadow Cinema of the American ’70s, will be published by Bloomsbury Press in Spring 2017.

The Moviegoer showcases leading writers revisiting memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by classic works of American literature.