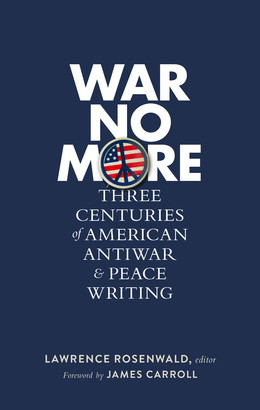

Library of America’s new anthology War No More: Three Centuries of American Antiwar and Peace Writing collects works by nearly 150 American writers who have questioned and challenged both particular wars and justifications for war in general from colonial times to the present day. The book’s editor, Lawrence Rosenwald, describes it as “a conversation not yet fully described by historians, nor fully available to activists, but living in these pages.”

A longtime pacifist, Rosenwald is the Anne Pierce Rogers Professor of English at Wellesley College and the author of Emerson and the Art of the Diary (1988) and Multilingual America: Language and the Making of American Literature (2008). He answered the following questions from Library of America just prior to the publication of War No More.

LOA: In your introduction to War No More, you write: “the intensity of American warmaking is the context from which the intensity of American antiwar writing emerges.” Could you expand on that notion? Why a volume of American antiwar writing?

Rosenwald: Sure. The United States has been a warmaking nation for most of its history. Its present military budget is by far the largest in the world. Its psychological character was famously if polemically defined by D. H. Lawrence: “the essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer.” This regardless of what one thinks of particular American wars. So American antiwar writing is directed against a formidable antagonist, namely, the powers of American warmaking—a “predator beast,” as Barbara Ehrenreich puts it, and an idea worked intricately into the fabric of our lives. And being directed against such an antagonist, it has a consistent urgency, a consistent necessity, that antiwar writing in other countries doesn’t always have, and a remarkable vitality and diversity.

LOA: What can this volume teach a thoughtful person today who’s wrestling with these issues—like a member of the millennial generation, for instance, who may never have known a time when we weren’t at war?

Rosenwald: One of the successes of American warmaking, I think, has been to marginalize and obscure the energies of American peacemaking. (A nonviolence trainer friend of mine likes to ask two questions of the people who attend her workshops. First, name ten wars. Almost everyone can do that. Second, name ten nonviolence campaigns, or in this context antiwar campaigns. Pretty much no one can do that.) So one thing this volume can do is register the presence, the abundance, the energy of American war resistance, and teach the millennial, or any thoughtful and open-minded person for that matter, that the field of possibility is greater than it seems, that warmaking is one possibility among many.

The other thing I’d note is that in popular culture, peace advocates are stereotyped—they’re meek, ineffectual, cowardly, elite, utopian. (At peace demonstrations, counter-demonstrators like to yell, “get a job.”) That too isn’t true; the opponents of war are as diverse as the supporters of it, are soldiers and laborers and immigrants and poets and preachers, reject some wars or all wars or nuclear wars, oppose violence or practice it, are young and old, men and women, serious and comic, confrontational or tricksterish. That too is something this volume can teach, and it’s a valuable lesson.

LOA: Both the book’s subtitle and your introduction distinguish between antiwar writing and “peace writing,” which you call “a less familiar category” and one “less easy to define.” What is peace writing?

Rosenwald: Most antiwar writing is, as its name suggests, oppositional, and most of the time it has to be; there’s a war on, or a war impending, and the thing to do is keep it from happening or bring it to an end. But that lets the war define the argument, and sometimes it’s important not to let that happen, to imagine what one would do if one ran things. (George Orwell said that pacifists weren’t serious because they couldn’t imagine exercising power. That’s a useful challenge for pacifists to accept.)

So the book tries to provide space for the peacemaking imagination, its metaphors and arguments: the Iroquois Tree of the Great Peace, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “beloved community,” Denise Levertov’s “peace, a presence, an energy field more intense than war,” Jane Hirschfield’s “I put peace in a warm place, towel-covered, to proof.” (It’s no accident that this list includes both the anthology’s earliest text and its latest; the enterprise of imagining peace is of long duration.)

LOA: War No More includes speeches, fiction excerpts, memoirs, a Calvin and Hobbes comic strip, folk songs, petitions, and a host of other genres and formats. What writer or piece do you think readers will find most surprising?

Rosenwald: If I had to pick a single piece that I imagine will surprise most readers (though not all), it’d be the excerpt from the Book of Mormon, with its extraordinary account of collective nonviolent resistance on the battlefield. No non-Mormon I know is familiar with this passage.

That said, though, I’d add that in some way there’s no answer to that question, because each reader will bring certain expectations to the book, and be surprised by the pieces that challenge or upend those expectations.

LOA: One of the collection’s pleasures is seeing acknowledged literary greats from Thoreau and Whitman to E. E. Cummings and Edna St. Vincent Millay rubbing shoulders with agitators, activists, and even enlisted men. What’s the connection between this tradition of writing and mainstream American literature?

Rosenwald: When I began work on the anthology, I thought the points of contact were relatively few, that antiwar writing took place at the margins of the canon, with a few canonical figures engaging in it and most of them not. I’ve come to see the points of contact as more abundant, and the distinction between margins and center less useful. (This is true also when one thinks about political writing generally, and notes, say, how many distinguished poets, from William Carlos Williams and Millay to the great Yiddish poets Moyshe-Leyb Halpern and Yankev Glatshteyn, along with “agitators and activists,” wrote poems on Sacco and Vanzetti.)

As you say, seeing the juxtapositions between canonical writers and marginal writers (or non-writers) is a source of pleasure; but in the long run, it might also be a way to reimagine the mainstream, the grand narrative of American literary history.

LOA: War No More arrives at a moment when many Americans are anxious about terrorism in general and ISIS in particular. In the public arena it’s accepted as a commonplace that these threats need to be met with force. What role do you see this book playing in that national conversation?

Rosenwald: That’s a very good question, and to answer it I need to go somewhat outside the anthology itself. There’s a general sense among scholars and activists and citizens that terrorism as manifested on and since September 11, 2001, is something new, which challenges our old ways of thinking and calls for new ones. I agree with that sense. And I don’t think that antiwar activists and theorists have sufficiently developed the new ways of thinking called for, or that readers seeking those new ways of thinking will find them here.

But the anthology still matters in this conversation because it critiques one of the old ways of dealing with terrorists, i.e., war. One can admit the challenge posed by terrorism and still argue that war is a bad instrument for combating it. In the view of the contributors who comment on them (and in mine, for what it’s worth), the two American wars since September 11th, in Afghanistan and Iraq, have been unsuccessful in combating terrorism, and are subject to many of the critiques and resistances directed against the wars that preceded them.

LOA: There’s a sense in our culture that antiwar sentiment is understandable, even commendable as long as we’re talking about conflicts like the Mexican War or Vietnam—but that World War II is off limits. Two of the most provocative pieces in the collection run directly counter to that view: Jeannette Rankin’s “Two Votes Against War, 1917, 1941” and Nicholson Baker’s “Why I’m a Pacifist: The Dangerous Myth of the Good War.” Did you have to think carefully before deciding to include selections that challenge the notion of “the good war?”

Rosenwald: Did I have to think carefully? In one sense, no; I knew about Baker’s piece long before I began work on the anthology, Jeannette Rankin was someone my parents liked to praise, I knew I wanted both of them in the book. And I knew also that an anthology that didn’t include accounts of opposition to World War II would be incomplete, not just historically but conceptually, unable to acknowledge that even the “Good War” was opposed by serious people for serious reasons. Any pacifist, and I’m one, has to think about that war, otherwise you’re not taking your pacifism seriously, and the anthology needed to show people doing that.

That said, I’d agree that these are among the most provocative pieces in the anthology. I had occasion to talk about the Baker piece in the context of a series of classes I co-taught with a local rabbi on Jewish traditions of peace and war. (Baker’s not Jewish, but much of his focus is on Jewish opponents of World War II.) I felt the temperature of the room drop, the atmosphere thicken, when we came to that piece, and at least one participant in a group of very thoughtful readers found it insulting. All the more reason for including it, I think; I wouldn’t want to give readers the impression that antiwar feeling is always “commendable” and never “provocative.”