By Carrie Rickey

The director tells Carrie Rickey that in his gorgeous, loving Edith Wharton adaptation, Wharton’s waffling “new” man takes on “a certain strength.”

To paraphrase film critic Richard Schickel, great novels are about the characters’ interior lives; bad film adaptations are about their interior decoration. Martin Scorsese’s version of The Age of Innocence is that rare literary adaptation in which interior lives and interior decoration illuminate each other.

| READ THE BOOK |

|

| Edith Wharton: Novels |

“I have always thought The Age [of Innocence] would make a splendid film if done by someone with brains—& education!” wrote Edith Wharton to Minnie Jones, her sister-in-law, in 1926, six years after the publication of Mrs. Wharton’s Pulitzer Prize–winning novel. Since there had been a silent-film adaptation in 1924, it is safe to assume Wharton thought it less than “splendid.” Prior to the first sound version, the author heard that someone named Katharine Hepburn—“a Hartford lady and a fine actress”—would be cast as Countess Olenska. Instead, Hepburn took the role of Jo March in Little Women (1933) while Irene Dunne played the Countess and John Boles her Newland Archer in the 1934 release drubbed by The New York Times for being “emotionally flaccid.” It played like a follow-up to Dunne and Bole’s hit _Back Street_—more Fannie Hurst than Edith Wharton.

Wharton’s hope for someone with “brains—& education!” was realized when Scorsese’s adaptation arrived in 1993 to generally approving reviews—though some wags questioned what the heck the director of Raging Bull, so knowledgeable about boxing gloves, was doing with (or to) a novel where opera gloves feature so prominently. “A gorgeously uncharacteristic Scorsese movie,” observed Vincent Canby in The New York Times. “Raging Bull in a china shop,” quipped The New Yorker’s Anthony Lane.

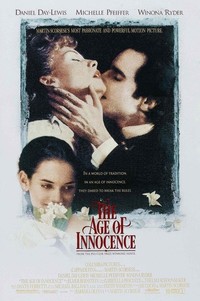

Scorsese’s film version is many things, none of them, happily, “emotionally flaccid.” More like palpably tumescent, and I’m referring not to the opening credits of flowers opening to reveal pistils and stamens, but to the considerable erotic heat between Michelle Pfeiffer and Daniel Day-Lewis. The plot is a romantic triangle that ultimately drives a wedge between desire and duty: On the eve of his wedding, Newland Archer (Day-Lewis) finds himself in thrall to the married Countess Olenska (Pfeiffer), who reciprocates his feelings yet persuades him to follow through with the wedding to her cousin, May Welland (Winona Ryder).

In 1993, Scorsese, a son of Little Italy’s working class, noted that he and Wharton, a daughter of the nineteenth-century Knickerbocker elite, weren’t so different. After all, weren’t his first great movie, Mean Streets, and her last great novel, The Age of Innocence, both the works of tribesmen keenly observing their tribes? As it reckons the tribal price of being a social transgressor and the psychic price of not being one, Innocence is thematically similar to many Scorsese films. It’s no surprise that he was as drawn to Wharton as Newland was to the Countess. Let’s say that the filmmaker had more success than Newland in consummating the relationship. Scorsese has even won over certain Wharton diehards at first shocked that he cast the fair-haired Pfeiffer as the Countess, described in the novel as a dark and “tall, bony girl with conspicuous eyes” and the small, brunette Ryder as statuesque blonde May Welland.

*****

Knowing the director’s love of genre movies, Jay Cocks, film critic and friend, handed Scorsese (who studied literature at New York University) a copy of Innocence in 1980. Cocks said, “When you do your ‘costume romance,’ do this.” It was another seven years before Scorsese read it. Ultimately Cocks and Scorsese collaborated on the screenplay. Between the completed film’s voice-over narration (read, with amused hauteur, by Joanne Woodward) and dialogue lifted straight from the novel, the spoken language in Scorsese’s Innocence is 75 percent Wharton and the other quarter a graceful telescoping of her shapely paragraphs.

An axiom of film school professors is that voice-over tells rather than shows. “I know that often when a film isn’t working, people say, ‘use a narrator’ and it can be a cheat, but that’s a simplistic interpretation of what narration does,” Scorsese told me in 2015. “I grew up watching movies like Kind Hearts and Coronets and Jules and Jim and I thought that narration was the voice of the storyteller. Does that tell rather than show? I don’t think so. For me, the storyteller’s voice is the entryway into the story.”

The way Scorsese uses it, Woodward’s voice-over—alternately satiric, plaintive, and penetrating—gently cues the viewer in on how to look at and listen to the film. As Wharton’s writing is so gorgeously modulated, Woodward’s voice-over, with its traces of her native Georgia drawl, is like music, on a par with Elmer Bernstein’s pensive orchestral score.

If the movie’s spoken language is distinctly Wharton, the film language is pure Scorsese. The stately horizontal pans suggest social decorum, and the swoopy crane shots and swoony close-ups communicate a dawning consciousness threatening to disrupt the proprieties. The camerawork tells the viewer when it is inside the characters’ heads by craning or zooming into portraits and intimate two-shots. And it alerts the viewer when it is in anthropological mode as it sweeps across rooms and down dinner tables. During banquets and balls, the camera often takes the chandelier’s perspective, the better to appraise the silver place settings and opulent centerpieces and flower arrangements—and to note the conformity of the dancers’ movements.

Scorsese has other narrative tools Wharton did not. He uses the optical effect of spotlighting to accentuate how Newland and the Countess are alone together in a crowded theater box. He employs the audio effect of making May’s chatter almost inaudible as she and Newland walk through a formal garden. These scenes emphasize how Newland hangs on to the Countess’s every word but tunes out his fiancée, bringing into high contrast how he listens to one and condescends to the other.

Then there is Scorsese’s use of color—not just the gowns and waistcoats and carpets and wallpaper, but pure, abstract color. When Newland and the Countess have a heated conversation about whether or not she should return to the Count, both see red, literally: The screen bleeds to crimson. When Newland sends yellow roses to the Countess, her joy bathes the screen in a sunny yellow. Wharton would be gratified that an artist in another medium seized upon visual correlatives for Newland and the Countess’s grand passion.

Wharton, like Ellen Olenska long an American exile in Europe, would also appreciate that the film made from her story of the clash between American respectability and Continental impropriety is so European in feel and texture. This, said Scorsese, is because his point-of-entry to historical dramas was Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard (shot, in part, in Ciminna, Sicily, the home town of Scorsese’s grandmother). Visconti’s 1963 film about an aristocrat who sees his way of life threatened by change boasts the pomp and richly saturated colors found in The Age of Innocence. Both films are melancholic about those colors’ fading, and both capture epiphanies in and out of magnificent balls.

There are two kinds of dance in Scorsese’s Innocence. At the Beaufort Ball where May and Newland announce their engagement, he leads his bride-to-be in a graceful waltz and she graciously follows, to the approval of polite society. The dance of Newland and the Countess is not the sort done in ballrooms. It is a martial art, a kind of emotional tai chi, of attraction and repulsion, advance and retreat. When first they meet as adults in the opera box as the soprano sings “The Daisy Song” (“He loves me, he loves me not”) from Gounod’s Faust, the Countess extends her hand to be kissed, in the European fashion. Newland bows instead, leaving the nonplussed Countess to retract her arm. Each of their encounters for the rest of the film has Newland moving toward the Countess and she retreating—or vice-versa. It is a dance where no one leads. Polite New York society disapproves, and ultimately intervenes, because it disturbs the social order.

Scorsese, who has directed five actors to Oscar-winning performances, elicits superb work from his three central actors. (In a very competitive year, only Ryder earned an Academy Award nomination for supporting actress.) When Archer is with May, he exhibits exquisite self-control. With the Countess, he loses it, and himself. As the filmmaker composed it, the false smiles and carefully calibrated amiability of these social animals are scored to the musical sounds of cheer. By contrast, the scenes between Archer and the Countess are so quietly intense that one can hear their hearts palpitate—and crack open.

Their unfulfilled affair builds to crescendo in the back seat of a carriage belonging to May. Newland peels off his glove and slowly, slowly his bare hand unbuttons Countess Olenska’s caramel-colored kid glove and he kisses the inside of her wrist. “Better than sex!” proclaimed Nora Ephron of Scorsese’s brief addition to this sequence of the novel.

*****

Each of us has a private Edith Wharton and however highly I regard his movie Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence is neither mine nor Wharton’s. And it is all the more powerful for that. The most critical difference between her novel and his film is that Wharton satirizes Newland, the “new” man who thinks he believes in divorce and that women should have the same freedoms as men, but can’t, or won’t, act on those beliefs. Reverting to “all his inherited ideas about marriage,” he weds May and thinks to himself, “There was no use in trying to emancipate a wife who had not the dimmest notion that she was not free.”

In 2015, Scorsese told me that he and Cocks were more sympathetic to Newland than was his creator. “Let me put it this way, more empathetic,” he said. “Most people say Newland wasn’t the real hero of the story. I don’t think he’s weak, but trapped. I still go back and forth about whether Newland has a certain strength.” Others might conclude that this human hypotenuse of Wharton’s love triangle lacks spine.

When the narrative jumps to the twentieth century, Newland is a widower of fifty-seven (the same age as his author), fully conscious that he “has missed the flower of life.” Stooped and gray, Daniel Day-Lewis’s Newland now is as faded as a withered bloom. Invited to the Paris apartment of Countess Olenska (near Les Invalides, like Wharton’s apartment on the rue de Varenne) along with his grown son, Newland cannot bring himself to go upstairs, to see the woman who gave him his first glimpse of a real life before he proceeded with the sham one.

Except for one haunting addition, the movie’s finale is straight from the novel. As his son goes up to the Countess’s apartment, the one with the awnings, Newland looks up and watches, noting a brilliant light shine through the open window. Then a manservant closes the window, the shutters and retracts the awnings, permanently sealing off Newland from the love of his life—the last step in their dance of romantic tai chi. He walks slowly away. Wharton might appreciate Scorsese’s haunting addition: The awnings are sunny yellow, like the roses Newland once sent Ellen.

Official trailer for The Age of Innocence (2:18)

The Age of Innocence (1993). Directed by Martin Scorsese. Written by Jay Cocks and Martin Scorsese, from Edith Wharton’s novel. With Daniel Day-Lewis, Michelle Pfeiffer, Winona Ryder, Miriam Margolyes, and Geraldine Chaplin.

Buy the DVD • Stream on Amazon Video • Stream on Google Play • Stream on Vudu

Carrie Rickey, longtime film critic for The Philadelphia Inquirer, writes for many publications, including Artforum, Art in America, and The New York Times on subjects related to art and film. Essays of hers are collected in The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock and Roll and the Library of America anthology American Movie Critics.