By Michael Sragow

You can stream thousands of movies with a tap on your smartphone, but how do you choose what to watch? “The Moviegoer” is here to help. In this biweekly column, top writers champion memorable films to watch or watch again, all inspired by or related to classic works from Library of America. The hero of Walker Percy’s novel The Moviegoer writes that he’s “quite happy in a movie, even a bad movie.” But his favorite moments usually come from great entertainments like The Third Man and Stagecoach. “The Moviegoer” salutes movies of that caliber. We hope these choices make you, too, quite happy.

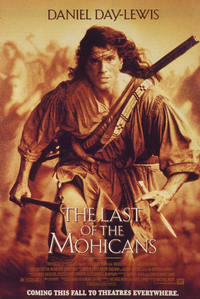

Michael Mann’s provocative revision of James Fenimore Cooper’s beloved The Last of the Mohicans is a thrilling foray into the American wilderness: a precursor to The Revenant that boasts an epic story to match its stunning images.

Shot in the Blue Ridge Mountains in 1991, Michael Mann’s inspired reimagining of James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans is one of the last of its tribe—an analog action saga with a surge of epic feeling. Set in upstate New York in 1757, at the height of the French and Indian War, this movie immerses audiences in dense old-growth forests, tumbling unspoiled rivers, caverns sprayed with mist and streaked with fire, and gusts of mountain air. Its hero, Hawkeye, played by Daniel Day-Lewis, is man, not superman. A settlers’ child who was orphaned, left with trappers, then brought up as an Indian, he hones and balances his senses to a tomahawk’s edge. His heroic feats are earthly, not otherworldly, whether he’s decimating Huron war parties with bladed weapons or using his long rifle to pick off potential killers of a British messenger. When Hawkeye loads his firearm with black powder while racing through battlefields, Day-Lewis—not some computer avatar—is doing those things simultaneously.

| READ THE BOOK |

|

| The Leatherstocking Tales: Volume One |

Day-Lewis won international renown as the witty, seductive hero of The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988) and earned an Oscar for his impassioned Christy Brown in My Left Foot (1989). He proves himself to be a knockout man of action in a film that became a critical and popular hit here and abroad and seduced even some scholars who bewailed its divergence from Cooper’s novel, beginning with Hawkeye’s movie name, Nathaniel Poe. (In Cooper, he’s Natty Bumppo.) This roughhewn master of survival now talks and moves with offhand elegance and ardor as he guides the two Munro sisters, Alice (Jodhi May) and Cora (Madeleine Stowe), through the enchanting and bloody mysteries of the Upper Hudson Valley wilderness, where a cougar casually peers out from the underbrush, and vicious assassins lie in wait. (Hawkeye’s name now fittingly recalls two gothic masters, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allan Poe.)

Mann eliminates any distance between Hawkeye and the Mohicans. Chingachgook (Russell Means), the Mohicans’ chief, adopted Hawkeye as a brother for bighearted Uncas (Eric Schweig). In Mann’s movie, Hawkeye is just what Leatherstocking fan D.H. Lawrence wanted l’homme Américain to become: not merely the “hard, isolate, stoic” killer of Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales but a new man for a new world. Hawkeye abhors imperial haughtiness and avarice and sees the future rolling westward before him. He’s on his way to Kentucky, or as he says, “Can-tuck-ee.” In a superb irony original to this film, Hawkeye becomes fully Indian while his nemesis, the vengeful Huron Magua (Wes Studi), develops a European capitalist’s worldview. He wants to monetize Indian assets and monopolize trade, appropriating and exploiting land and fur from other tribes.

This Hawkeye embraces a holistic Native American vision of ecology, community, and the universe. When he and the Mohicans take down an elk in the opening scene, they pause as Chingachgook pays homage to the fallen animal. Hawkeye supports colonial militiamen’s right to leave British forts to defend their homesteads if the war spreads to their farms. In a quiet moment, Hawkeye tells Cora that the mother of the cosmos died during the birth of the sun and the moon, so the sun gave her body to the earth to be “the source of life,” then summoned stars from her breast and threw them into the night sky, “to remind him of her soul.” Day-Lewis, the second son of British poet laureate C. Day Lewis, delivers grass-roots poetry as surely as mortal blows. Most controversially and thrillingly, Mann and Day-Lewis imbue the book’s celibate Hawkeye with uninhibited sexuality. Stowe—a witty and resourceful actress—perfectly captures Cora’s response: an erotic awakening in full bloom.

The main action kicks in when Cora and Alice Munro, escorted by Major Duncan Heyward (Steve Waddington) and the two-faced Magua, set out to visit their father, Colonel Edmund Munro (Maurice Roeves), just when the French general, the Marquis de Montcalm (Patrice Chéreau), tightens his siege around the colonel’s forces at Fort William Henry. Mann renders this scenario with a visual depth and élan that hark back to the voluptuous yet sinewy color images of N. C. Wyeth’s oil-on-canvas illustrations for the 1919 Scribner’s Classics edition. “N. C. Wyeth!” Mann exclaimed when he recently told me about his most galvanizing influences. “That’s what got me!” Hawkeye and his Mohican family rescue the Munros and Major Heyward from Magua on mountain paths and in canoes right out of Wyeth. Throughout, Mann and his cinematographer, Dante Spinotti, combine the zesty brushstrokes and robust dramatic spirit of Wyeth’s illustrations with the panoramic scale and luminosity of Hudson River School artists like Alfred Bierstadt and Thomas Cole. (They also sprinkle the film with indelible details from Benjamin West’s painting The Death of General Wolfe.) Mann’s mix of documentary nitty-gritty and pictorial splendor makes familiar frontier motifs fresh again, like Cora marking a trail with broken branches and Hawkeye zeroing in on them, or the breathtaking cliff-side combat between Magua and Uncas and then Magua and Chingachgook. These scenes are as captivating as they were in Maurice Tourneur and Clarence Brown’s 1920 silent version, the most faithful screen adaptation of Cooper and, next to Mann’s, the most artful and compelling.

Mann reworks Cooper’s narrative for maximum limpidity and punch. He wants the audience to feel caught up in the romance and in the cross-racial male bonding without ever losing sight that it unfolds in a war zone. What drives Mann’s plot is Magua’s determination to avenge himself on Colonel Munro and his troops for the murder of his own children and the general ruination of his life. What complicates the plot is Hawkeye’s devotion to Cora and Major Heyward’s hope to marry her and carry her back to England.

| BUY THE BOXED SET |

|

| The Leatherstocking Tales (Two volumes) |

Mann deletes the more fanciful aspects of Cooper’s novel, like Hawkeye impersonating a bear, as well as the entire character of a comic-grotesque psalm singer. But he retains and re-orders the ambushes, the getaways, the siege, and the Indian massacre of retreating troops and civilians from Fort William Henry. Mann packs so many levels into the action that he often introduces it with impassioned tableaux: cannoneers slowly haul their heavy artillery while French soldiers dig trenches that will bring these big guns within close range of the fort; a thick red line of British soldiers march through a forest trail without realizing that Hurons are waiting to surprise them on either side. The action ensues with startling clarity. There isn’t a wasted slash or shot, so each one carries the impact that an entire fusillade would in a lesser film.

But this movie is more than a vigorous exercise in kinetic style. It’s also a triumph for Mann’s iconic and iconoclastic sensibility. Mann considers Cooper’s novel a “cartoon” vision of frontier life in 1757. In his view, it depicts “nice” Native Americans like Chingachgook and Uncas as “noble savages” who are “inefficient stewards” of their land and thus not worthy of its ownership. And, Mann reminded me, Cooper’s father was Judge William Cooper, the founder of Cooperstown, New York, who, according to Cooper biographer Stephen Railton, “claimed to have been responsible for settling more acres of American forest than any man of his time.” Mann sees the book as “a whitewash of land grabs and cultural imperialism.”

It’s true that Cooper can be condescending toward Native Americans even at his most beneficent. “You are a just man, for an Indian,” Cooper’s Hawkeye tells Chingachgook. And Hawkeye insists on calling himself “a man without a cross”—that is, without a drop of Indian blood in him. Yet Cooper’s novel does recognize, on the very first page, “the cold and selfish policy of the distant monarchs of Europe.” Hawkeye turns his back on white men’s greed and their pale, imported proprieties. Cooper also touches on the sexual charisma of men who attack life physically, like Uncas and, amazingly, black-hearted Magua. (In the book, Uncas, not Hawkeye, is Cora’s love match and even Magua catches her eye. But Cooper’s Cora is a woman with a stain—or as Hawkeye would put it, a cross: she has black blood in her.)

Mann himself thinks that he has turned his back on Cooper. What he’s really done, perhaps, is to liberate Cooper from himself. Hawkeye’s and Cooper’s admiration for the Mohicans’ way of life—their blend of pragmatism and chivalry, and their genius at warfare, hunting, and navigating their environment—emerges stronger than ever in Mann’s version of the tale.

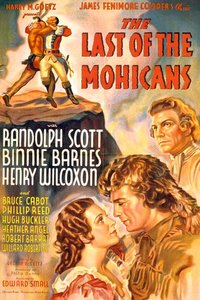

Mann’s determination to make his own version of Cooper’s novel stemmed from a Chicago neighborhood showing in his childhood of George Seitz’s workmanlike 1936 movie, starring Randolph Scott as Hawkeye. The frontier imagery “roiled around” inside of him for decades, while he broke through as a director and explored urban crime with movies (Thief, Manhunter) and TV shows (Miami Vice, Crime Story). Mann told me that when he re-screened Seitz’s movie as an adult, he thought it was “unwatchable,” but when he retrieved Philip Dunne’s script he found it “wonderful.” Dunne’s screenplay transformed Hawkeye into a romantic figure and dramatized rifts between colonial settlers and the British. Mann admired its “excellent” construction.

As a novel, The Last of the Mohicans has its own picturesque origin story. According to Cooper’s eldest daughter, Susan Fenimore Cooper, the book was launched when her father paused inside the caves beneath the rushing waters of Glens Falls while touring the Upper Hudson Valley with some aristocratic English visitors. “The travelers were struck with those stern, somber rocks,” she wrote, “and the flood falling in fantastic wreaths of white foam about them.” Edward Stanley, the future three-time Prime Minister of the U.K. (and translator of Homer), wrote in his diary that Cooper exclaimed, “I must place one of my old Indians here.” That Indian, of course, turned out to be Chingachgook. Cooper dictated part of the novel while bedridden with fever. When his wife, Susan De Lancey Cooper, took down the notes, she thought they were the product of delirium. (Mark Twain, in “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses”—an essay Mann quotes approvingly—questions whether another Cooper novel, The Deerslayer, is art or “just simply a literary delirium tremens.”)

When Mann recalls searching for locations in the Blue Ridge Mountains, then building a fort, a colonial farm and an Indian village from indigenous materials, he conveys the imaginative release Cooper must have experienced with his forays into the wild. Mann speaks of “months climbing these buttes” looking for a place to build the fort, then knowing he was going “to close 26 miles of state highway, and get the FAA to reroute planes so there are no contrails [vapor trails]. You wind up moving through a tremendous amount of nature. And two things happen: you get a feel for it, so it’s almost like you’re duplicating what these people actually did, and there’s a more intense appreciation of it. With the actors you don’t have to say, ‘See that blue screen over there—that’s not really a blue screen, that’s really Lake George.’”

At the outset Mann says he asked himself, “Who is Hawkeye? Where did that idea of Hawkeye come from?” He soon realized that “the attraction of Euro-Americans to Native Americans’ culture and their skill sets was very powerful.” Frontiersmen like Daniel Boone and America’s eighteenth-century “special ops” force—Rogers’ Rangers—generated popular legends. Their tracking, fighting and survival skills were, Mann says, “learned from Native Americans: that’s where it all comes from.”

Mann’s goal throughout his career has been “to find more exciting drama in the way things really are.” He pored over the diaries of Comte de Bougainville, General Montcalm’s aide de camp, as well as Francis Parkman’s history of the French and Indian War (collected in the Library of America volume Francis Parkman: France and England in North America: Volume Two). His embrace of Native American culture went beyond reading about historical figures. He cast American Indian Movement co-founder Russell Means as Chingachgook and AIM leader Dennis Banks in the small role of Ongewasgone. Mann tapped into the culture of “present-day Mohawks because there is a real coherent unified legacy that is alive and still functions among the Iroquois.” The nations of the Iroquois Confederacy were the dominant Native Americans in the northeastern colonies. The Hurons, the main French allies in this movie, spoke an Iroquoian language and shared Iroquoian mores. The director also used these customs to fill in the blanks of Mohican traditions that have been lost. His findings informed Hawkeye’s love for Cora. “In Iroquois culture, in courtship, there was free love,” Mann says. “There were monogamous relationships, and there was divorce, with property being split and inherited matrilineally. The whole social structure and the mores by which you see a woman and you like her—those were different and that’s exactly what Daniel is doing when he just looks at her with that bold stare. It’s not lascivious in any way. It’s totally, totally candid.”

The fierce and lucid employment of weapons so antique that they seem alien makes the battle scenes both hypnotic and thrilling. “It’s based on the technology,” says Mann. “How do you fight with a tomahawk? We figured that the movements would have been very similar to saber fighting, because a tomahawk is like a section of a saber, with added weight behind the cutting edge. So we got eighteenth-century saber-fighting manuals and derived X number of blows and parries.”

Mann values the truth and drama he can find in the library and in the field, but, he says, “that’s not what lights the fuse and gets you going. It is absolutely visceral. The visceral hook for me was the Wyeth illustrations and my recall as a small boy seeing the 1936 movie.” Mann’s Last of the Mohicans is a masterly fusion of history, fiction, personal obsession, and popular mythology. Without IMAX or 3-D, watching it is a you-are-there experience. From Cooper’s legendry, Wyeth’s transcendent storybook imagery, an exotic B-movie with a first-class script, and some keen first-hand observations, this most sensory of directors creates something magically new. You take it in through your pores; it fills your heart and electrifies your senses.

Official trailer for The Last of the Mohicans (1:58)

The Last of the Mohicans (1992). Directed by Michael Mann. Written by Mann and Christopher Crowe from James Fenimore Cooper’s novel and a script by Philip Dunne (from an adaptation by John L. Balderston, Paul Perez, and Daniel Moore). With Daniel Day-Lewis, Madeleine Stowe, Wes Studi, Russell Means, Jodhi May, and Eric Schweig.

Michael Sragow is the curator of Library of America’s Moviegoer feature. He is the West Coast Editor and a film critic for Film Comment and author of Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master.