A recent post on Women’s Voices for Change begins, “It seems each year that October 27, Sylvia Plath’s birthday, brings more darkness around her memory.” California’s Poet Laureate Carol Muske-Dukes then tries to lessen that darkness by calling attention to the warmth in Plath’s work, “the muscularity of her efforts, her relationship to the natural world, and the woman she was yet to be.”

Getting past the Sylvia Plath myth to get to the poetry seems to be more than an annual problem. In 2001 psychologist James C. Kaufman coined the term the “Sylvia Plath Effect” (“the phenomenon that creative writers are more susceptible to mental illness”). In the five decades since her death a rancorous debate has raged over which of several biographies portrays her life more accurately—and each one struggled to shift the focus from her life to her work.

Yet Plath is different from Keats and Rimbaud and other revered poets who died young. As A. Alvarez writes: “For Plath, death, and the rage and despair that attend it, were her subject, and she followed the logic of her art to its desolate end. Her last poem, ‘Edge,’ is literally her own epitaph. Her life and work are not just inextricable, they seem at times virtually indistinguishable.”

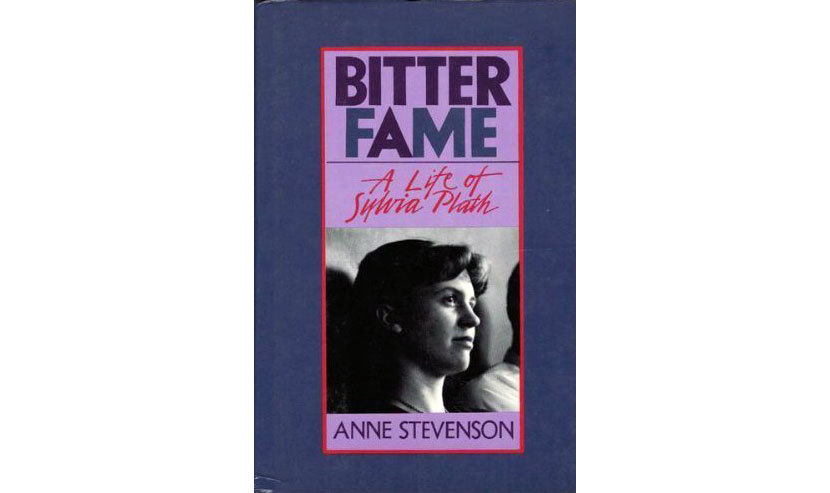

Much of the rich appeal of Bitter Fame: A Life of Sylvia Plath comes from biographer and poet Anne Stevenson’s unraveling of the sometimes mystifying imagery of Plath’s poems by identifying correspondences with her life. The seven sections of “Poem for a Birthday” from 1959, for instance, become more accessible if we know that lines like “Now they light me up like an electric bulb” and “Heating the pincers, hoisting the delicate hammers” relate to the electroconvulsive therapy treatments Plath received after her first suicide attempt in 1953. The “dubious note of hope” Stevenson finds in the last section “The Stones” contrasts sharply with the “merciless, lashing rage” in “A Birthday Present.” Written in September 1962, this was one of the first poems created in the five-month blaze of creativity that preceded Plath’s death and is one of the most memorable of those published posthumously in Ariel (1966).

Anne Stevenson devoted three years of her life to writing Bitter Fame, which was authorized by the estate. Although Alvarez, who knew Plath briefly, was outraged by the biography for both personal and literary reasons, Janet Malcolm’s controversial investigation into the art of biography, The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath & Ted Hughes, ends by finding Stevenson’s account “by far the most intelligent and the only authentically satisfying” of all the biographies. For Stevenson, the author of more than a dozen books of poetry and prose, the contretemps over the biography threatened to overshadow her career as a poet. That danger was remedied somewhat in 2007 when the Poetry Foundation awarded 74-year-old Stevenson its Neglected Masters Award. Andrew Motion has called her “one of the most individual poetic voices to have emerged on either side of the Atlantic in the last fifty years.”

Stevenson has written three poems for Plath: “Nightmare, Daymoths”; “Hot Wind, Hard Rain”; and “Letter to Sylvia Plath.” She wrote “Letter” in 1988 just as she was finishing her biography, as one stanza acknowledges:

Dear Sylvia, we must close our book.

Three springs you’ve perched like a black rook

between sweet weather and my mind.

At last I have to seem unkind

and exorcise my awkward awe.

My shoulder doesn’t like your claw.

“Letter to Sylvia Plath” ends on the kind of affirming note that seems appropriate as a birthday remembrance:

We learn to be human when we kneel

to imagination, which is real

long after reality is dead

and history has put its bones to bed.

Sylvia, you have won at last,

embodying the living past,

catching the anguish of your age

in accents of a private rage.