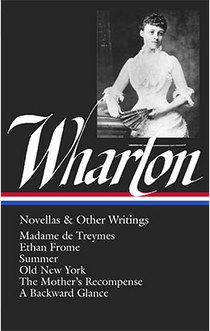

Major works:

The House of Mirth • The Custom of the Country • Ethan Frome • The Age of Innocence

Edith Wharton’s vocation was confirmed already in childhood, when her most “intense & enduring” pastime was improvising long narratives before she had even learned to read: “This devastating passion grew on me to such an extent that my parents became alarmed.” When in 1902 she showed her first novel, set in eighteenth-century Italy, to Henry James, he expressed admiration for her writing (“exquisitely studied and so brilliant & interesting from a literary point of view”) but strongly encouraged her to turn her attention to her own time and place: “There it is round you. Don’t pass it by—the immediate, the real, the ours, the yours, the novelist’s that it waits for. . . Do New York! The 1st-hand account is precious.” The immediate fruit of this advice was a masterpiece, The House of Mirth, in which Wharton cast a revealing light on the world of privilege in which she grew up, and whose dissection of the hidden social barriers and pressures among the upper classes of turn-of-the-century New York remains unsurpassed. A long series of masterful novels and stories followed, ironic, richly detailed, and capturing both the high comedy and the tragic contradictions of her world.

A Backward Glance

Edith WhartonOne of the most depressing impressions of my childhood is my recollection of the intolerable ugliness of New York, of its untended streets and the narrow houses so lacking in external dignity, so crammed with smug and suffocating upholstery. How could I understand that people who had seen Rome and Seville, Paris and London, could come back to live contentedly between Washington Square and the Central Park? What I could not guess was that this little low-studded rectangular New York, cursed with its universal chocolate-coloured coating of the most hideous stone ever quarried, this cramped horizontal gridiron of a town without towers, porticoes, fountains or perspectives, hide-bound in its deadly uniformity of mean ugliness, would fifty years later be as much a vanished city as Atlantis or the lowest layer of Schliemann’s Troy, or that the social organization which that prosaic setting had slowly secreted would have been swept to oblivion with the rest. Nothing but the Atlantis-fate of old New York, the New York which had slowly but continuously developed from the early seventeenth century to my own childhood, makes that childhood worth recalling now.