Tom Nolan is the editor of The Library of America’s recently published title Ross Macdonald: Four Novels of the 1950s. Here, in the last of three exclusive Reader’s Almanac posts about Macdonald’s life and work, he focuses on the ostensibly “friendly and healthy competition” Macdonald had with his wife Margaret Millar, herself a distinguished and prolific author of suspense novels, and what it was like for their daughter Linda to grow up as the only child of two successful writers.

A case could be made that Kenneth Millar (Ross Macdonald) and Margaret Millar (a pioneer of psychological suspense) were and are the most distinguished non-collaborating husband-and-wife couple in the history of mystery fiction. And there’s no doubt that the pressures and tensions of their 45-year marriage, which included the raising of a child, found their way into many if not most of their combined 52 novels. Early in their careers, the Millars told friends that many of their fictional characters’ best lines came from arguments they themselves had with each other.

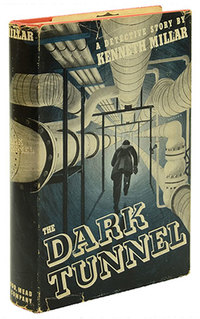

Kenneth broke into print first, with short stories, reviews, poems, and humor pieces in Toronto magazines—in part to pay for his wife’s 1939 maternity-hospital bill. Maggie was the first to write and sell a mystery novel with The Invisible Worm in 1941. Ken published his debut thriller The Dark Tunnel in 1944. There ensued what he would call a “friendly and healthy competition” between two writers who for many years more or less matched each other, book for book.

Less healthy and friendly were the squabbles the Millars had over how to bring up their child. Maggie was determined to raise daughter Linda “scientifically” following the dictates of John Broadus Watson’s later-discredited “behaviorism,” which put demands on a child to perform but allowed little or no parental affection. Ken thought this idiotic and harmful. The Millars’ disagreements sometimes became physical, which could have done their observant daughter no good.

Once her family moved to California, and as she grew older, Linda felt more and more out of place in her own home. Both her hyperintelligent parents were always busy writing. Their daughter became a precocious reader of authors far above her grade level: Theodore Dreiser, James T. Farrell, Carson McCullers—and her own mother and father, in whose works she recognized thinly-disguised portraits of each other and of herself.

Grade-school counselors warned Ken and Maggie of Linda’s social maladjustment. By adolescence, she was secretly running with a wild crowd, getting drunk, and having sex. Her parents remained oblivious and hoped college would prove her salvation. But in 1956, 16-year-old Linda was charged with vehicular homicide in a hit-and-run accident in which a 13-year-old pedestrian was killed. After a suicide attempt and three months’ confinement in a mental hospital, Linda was found guilty in juvenile court of two felony charges and placed on eight months’ probation.

The family moved north to Menlo Park, where Linda completed high school and was accepted to UC Davis. Her parents returned to Santa Barbara. In 1959, Linda disappeared from the Davis campus for eight days, during which her father went on a well-publicized search for her and (with the help of private detectives) found her in Reno.

The rest of Linda’s life was comparatively placid—she married a young engineering student she met at UCLA and the couple had one child, a son—but she and her parents were marked forever by the events of her teenage years, traumas which often found their way (sometimes by anticipation) into her parents’ novels.

Linda died in 1970, at the age of 31, when her son was seven. Her death drove an emotional wedge between Maggie and Ken. Maggie stopped writing for six years, while Ken worked at a slower pace than before. In time, Margaret Millar once more picked up her pen, producing her last books after Ross Macdonald, diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, was no longer able to work.

Writers used their imaginations, Ken Millar once said, to allow readers to undergo extreme experiences they would not be able to endure in real life. But Ross Macdonald and Margaret Millar both imagined dire happenings and also endured them. Both paid a high price for their fiction’s authenticity—as did their only child.

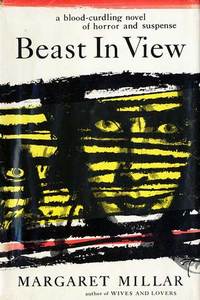

(Readers, take note: Margaret Millar’s 1955 novel Beast in View is included in Women Crime Writers: Eight Suspense Novels of the 1940s & 50s, a two-volume set released by The Library of America in September 2015. Visit the special Women Crime Writers companion website for complete information on the eight novels and their authors.)