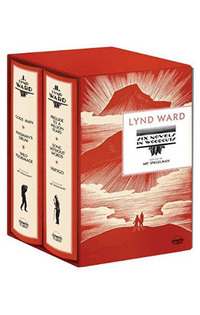

In connection with the publication in October 2010 of the two-volume boxed set Lynd Ward: Six Novels in Woodcuts, edited by Art Spiegelman, Rich Kelley conducted this exclusive interview with Spiegelman for The Library of America e- Newsletter.

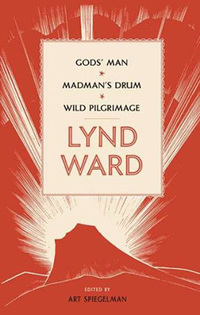

LOA: Lynd Ward: Six Novels in Woodcuts collects into two volumes the six word-less novels Ward created between 1929 and 1937. Needless to say, it’s quite unusual for The Library of America to publish novels without words. What is it about Ward’s approach to storytelling that puts him in the company of writers like Herman Melville, John Steinbeck, and Mark Twain?

Spiegelman: The writers in the Library of America series are often, although not always, pioneers of a sort. There are ways in which one can argue that Melville reinvented the novel, that Mark Twain invented forms that never existed before. In those terms Lynd Ward can definitely hold his own. What is it to tell a story in book form? Does it mean that one only has access to the alphabet? These questions have come under major scrutiny recently as part of the great technological funnel we’re living through. At this moment the book really is an anxious object. I wouldn’t be that surprised if in ten years The Library of America is a Kindle or an iPad app. Because The Library of America’s tradition has been that it takes on artists who have aspired to make books in the past 200 years, the “book-ness” of what they create is as much a part of their contribution to literature as the total content, and Lynd Ward was way ahead of his time, a visionary, in understanding the importance of the book as an object, as a container of a kind of content. His books were made with great attention to that container and he worked within it as precisely as a concrete poet works with language.

LOA: These volumes include the essays Ward wrote for Storyteller Without Words, the now out-of-print collection published in 1974. In these essays Ward describes a creative process that seems to strive for the purest form of pictorial narrative possible. “If understanding is dependent on the words,” he writes, “the narrative is probably more properly described as a work of illustration”; where the text is primary, the art, “no matter how impressive,” is secondary. Reading these books is not like reading novels or like looking at paintings. Is there a mental adjustment we need to make to properly appreciate what Ward is doing here?

Spiegelman: All novels require some mental adjustment in order to understand a writer’s meaning. But yes, in Ward’s books you have something that has its own operating system. This requires slowing down to understand it. Come at it from one angle and you’re looking at a bunch of incoherent, unconnected pictures. From another angle you see a very tightly woven narrative that rewards contemplation and a revisiting of how it’s told as well as what’s being told. Each of his books teaches itself. As you’re reading you understand better how to read each book—the speech and rhythms of what one can find as one revisits a picture. As Susan Sontag pointed out in her essay “On Photography,” pictures are scary because until they are actually contained by words their meanings are not containable. The words that describe what’s happening in a news photo actually refocus you to not look. The whole point of Ward’s work is to make you look and understand.

LOA: How important do you think it is that the artwork in each book appears only on the recto (or right-hand) pages?

Spiegelman: It’s the ideal form for this work. I’m pleased that The Library of America agreed to do that rather than putting them all smashed together in one book. It makes you take the measure of the picture because it’s not competing with anything else in the closed field you’re looking at. It works far differently than how it was presented in Storyteller Without Words in the ’70s—sometimes there were four images on a page—that forced Ward’s work to become a comic strip and it didn’t respect the central impulse that formed the work. It was a bit like looking at a cinematographically beautiful film on a YouTube video. It was a reduction in every sense. Ward was interested in the book. The kind of markings around each picture. The kind of paper the book’s printed on. He actually became a printer/publisher in order to control the elements that made the experience of reading the book the experience he wanted. He didn’t take for granted that it had to be a certain way. Having this kind of control allowed him to make something that almost insists that every copy of the book is the original work of art.

LOA: Can we talk about Ward’s technique? In his introductory essay, “The Way of Wood Engraving,” Ward mentions being inspired to create a novel using woodblocks after seeing similar kinds of books created by the Belgian artist Frans Masereel and the German artist Otto Nückel. Masereel worked in woodblocks cut with the grain of the wood. Nückel worked in leadcut prints. Ward by contrast worked with woodblocks cut against the grain, a technique properly called wood engraving. Why do you think he chose this technique and how well does it suit what he wants to do?

Spiegelman: Ward’s way of approaching the wood is appropriate to a very white Anglo-Saxon Protestant man with a great, great work ethic who loves working with his hands, loves the craft aspect as well as the expressive aspect of what he does. His pictures are a full expression of that sensibility. So it’s hard to say: did he choose wood engraving because he wanted to make a certain kind of picture, or did he make a certain kind of picture because he liked to work with his hands? Wood engraving is a careful process and an exacting one. There are many other ways to get an image across without having to get your fingers all bloody. There’s a lot that can go wrong if you chop at the wrong angle. I think his choice had to do in part with the roots of the tradition of printing, making books as objects. He cared about the history of type, the history of representing images—the history of woodcuts goes back to the origins of bookmaking as we’ve come to know it. I think that’s the core reason.

Ward first became interested in the idea of stories without words while he was studying printmaking in Germany and Masereel’s were the first works he discovered. What’s interesting about that group of three, Masereel, Nückel, and Ward: not only did they communicate in different media, their work expressed different sensibilities. Nückel did just one experiment, Destiny, in this area of stories without words. His work is informed by a delight in light; his pictures are infused with an almost impressionist way of making the image known. Masereel’s many works are freely hewn, chunked exuberantly into the wood and have a blunt visual approach. He is very eager to distort and cascade loud layers of information into pictures. For the most part Ward’s work has a methodical quality. Even in his first book, Gods’ Man, the pictures are very consciously rooted in the early tradition of what a woodcut might look like. He uses its emblematic qualities more and more as he goes on and pursues detailed picture-making to great reward.

LOA: You note in your introduction that Ward’s first novel, Gods’ Man, is “the most emblematic and popular of his six novels.” Do you think this is due to the Faustian theme or is his storytelling more straightforward here?

Spiegelman: None of the above. If you were going to play Jeopardy and the answer was Lynd Ward the question would more likely refer to Gods’ Man than any of Ward’s other works, which didn’t hit as hard into the bullseye of the culture. Gods’ Man hit that bullseye mostly because of the novelty rather than because of the story. Nobody had seen anything quite like it before and they were ready to see it. Had he somehow magically been able to change the order of his books, it could have been that Wild Pilgrimage became the book that everyone associates with Lynd Ward. His books are not all fully successful. It is true that his first book in a way is the most immediately intelligible—a quick run-through will allow you to get the elements of the story, which is an asset for anyone approaching the work cold. But in some ways it’s not his best book—it was just the first of its kind that Americans saw and received. Masereel’s work was quite well known in parts of Europe but it hadn’t reached America yet so there was nothing that had even a family resemblance that one could compare Ward’s work to. Now we look at it and say “Ah, that’s interesting how it overlaps with the notion of comics,” but at the time the appeal wasn’t coming from that place at all. The book also had a luxuriousness without being pricey. It wasn’t a rarefied art object—it was affordable and looked like something you would want to hang on to and read a number of times.

LOA: In one of his essays Ward describes the difficulty in finding the right interval between scenes when portraying the developing action of a story—jump too far and you lose the reader, move too slowly and you’re repetitious. In his second novel, Madman’s Drum, do you think his interest in creating a wider cast of characters interferes with his storytelling?

Spiegelman: Yes, Madman’s Drum is categorically the most confused of his books. It’s beautiful in some places, some of the images are great. He got very ambitious and I salute the ambition—but I can’t say that he realizes that ambition and I don’t think he would say that either. The things that went strange in this work informed decisions he made in what I would say is his greatest work, the last one, Vertigo. He wouldn’t have been able to do Vertigo without having made the rather interesting mistakes that kept happening to him narratively in Madman’s Drum. The problem comes with using pictures as words. This means getting into a kind of symbol-making. You can say “This represents evil,” “This represents good,” but you don’t have the nuance of easily saying: “And this, this represents ambivalence.” There’s no visual icon that’s part of a shared vocabulary.

In Madman’s Drum Ward tried to tell a story spread across generations that had themes that reverberated and had a layered narrative of how different people, connected by blood, work through their lives. In the course of trying to give a back story to every character—that was the most interesting thing he tried to do—he wanted each character to have their own narrative reality, something that one associates with a good novel. That’s easier for George Eliot than it is for an illustrator trying to tell a story. The result is that this book requires a lot of rereading, not to enter deeper into the story but to penetrate what the hell the story is. Although there are sequences that are done very, very deftly and intelligently, this book doesn’t have the streamlined quality of Gods’ Man. Ward got more ambitious visually in Madman’s Drum and tried to engrave more finely in the wood; sometimes this led to good results but sometimes to something a bit murkier. I don’t mean to put the achievement down. It’s an interesting work and there are things I like about it. But because of the aspect of kitschiness in Gods’ Man that led Susan Sontag to put it into her canon of works defining “camp”—and because Madman’s Drum strives but fails at its ambition—I consider both interesting more for the territory they open than for the territory they ultimately colonize.

LOA: In your introduction you call Ward’s third work, Wild Pilgrimage, “the most accessible and satisfying” of his works. Why?

Spiegelman: In Wild Pilgrimage Ward solves the problem that he set up for himself in his previous two books. You see a really industrious forward movement of an intelligent mind working in brand-new terrain. The clarity of Gods’ Man is regained after his sophomore slump in Madman’s Drum. The picture making itself has a new kind of sinuous assurance to it that comes with the gaining of highly developed design skills. I find the visual surface of the book its most engaging aspect. The parallel tracking of interior and exterior life is really interesting in terms of art: how nuanced can you make a narrative by having a psychological component to it? Wild Pilgrimage rewards revisiting not in terms of “what the heck was that guy trying to say?” but in terms of “Oh, this actually has the pleasures that one gets from a piece of music or a poem.” It’s satisfying because the story is thematically simple: it allows one to take the pleasure from the telling and the nuances of what is being told. It reveals itself with revisiting. The work has some of the same problems as Gods’ Man in that it could be looked at as kitschy now, but it also has a kind of giddy, self-assured bravery that deflects charges of its being unsophisticated.

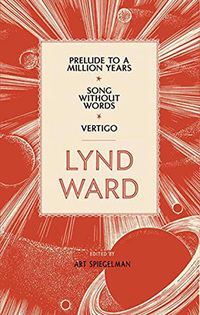

LOA: The two shorter novels, Prelude to a Million Years and Song Without Words, seem to have more of a prose-poem quality to them, and the individual plates have a more iconic quality. Was Ward aiming at something other than storytelling in these works?

Spiegelman: Not necessarily more or less than in Wild Pilgrimage. The meanings are clear in the pictures. He is trying to canvas a different span of time than in the other books. I don’t see it as less narrative. They are what they are: they’re novellas rather than novels. Some subjects turn into a short story and others turn into a novel. Each of these has a musical aspect. Song Without Words insists on that. It’s important to think of Ward as working in the moment, both in terms of the history of technology and mass media and the history of American social reality and the politics of the ’30s. They inform his work. Silent film can also be credited with creating this eruption of form: the wordless novel. Think of these shorter works as a short film but not necessarily a one-reeler. They try to take on a smaller chunk of narrative in order to make it fit into a short subject, more like the way Maya Deren, Luis Buñuel, and avant-garde filmmakers were beginning to make films that stretched the envelope in the ’30s.

LOA: Ward took two years to create his last novel, Vertigo, an epic masterpiece of 230 wood engravings that follows the intersecting stories of three characters, The Girl, The Boy, and An Elderly Gentleman, from 1929 to 1935. Here virtuosic artwork, mastery of characterization, and storytelling all coincide. Did Ward finally achieve here what he set out to do in 1929 in Gods’ Man?

Spiegelman: First, two years sounds actually very efficient for a very hard worker. I believe it could easily have taken longer than that.

Vertigo is where it is interesting to watch Ward’s mind at work. His sensibilities are very different from mine. I can’t say that this artist has a lightness of touch ever. His pictures can move toward the histrionic—in the two short works, for example—but in Vertigo he was able to use everything he had made before. It is symphonic. It ambitiously attempts to make the great American novel. This particular work is much more difficult to apprehend in the first viewing. When I first looked it over I got it but now I realize that I never stopped to receive it. It really is novelistic in its ambitions and its structures. More than any of the other works it is very, very subtle and rewards rereading. The great achievement of Vertigo is that Ward solves the central dilemma that comes with this territory: to try to deploy images to tell a story without resorting to cliché symbols.

The singular achievement is the character of the capitalist, the elderly gentleman. He is no longer a cartoon character decorated with dollar bills but is some- one who’s rendered with a kind of melancholy sympathy and empathy. For someone whose politics were so specifically opposed to what that character represents, the fact that Ward allowed him to be in some way quite hapless rather than the instrument of Satan makes the whole work really come to life. Its nuances make it come to life; its structure makes it come to life. He did something that’s quite brilliant by not having the three main characters connected in an overt way. Telling a story without language means you have to work from some shared vocabulary that people have. You can’t introduce pictures and create any old story out of them. So it starts as a sort of a boy meets, loses, and sort of gets girl. But then Ward actually creates something symphonic. Not having the boy or the girl directly connected to the other main corner of the triangle. They don’t meet. The girl and the capitalist, the elderly gentleman. They aren’t affected by his actions as directly as someone pointing and saying “Hang him.” They are connected through ambient and thematic ties that are way bigger than the characters. The individual trajectories are what connect them. The one picture where they do connect, the transfusion scene, is kind of chilling. It works emotionally. The transfusion of the blood can be seen as this vampiric act that connects the young man to the old man. It’s depersonalized. The old man doesn’t know whose blood he’s taking but he’s taking blood in the same way he is in the economic dimension.

LOA: Is this why Ward never finished another novel in woodcuts? Because he had accomplished what he wanted to do?

Spiegelman: Probably. He set himself a very, very difficult problem and it took him eight years to solve it. Once accomplished, the urgency left that particular field. He was highly regarded and in demand as an illustrator and he was also insisting on the dignity of illustration as an endeavor. And he was a bit besieged by the tidal shift that happened with the onslaught of modernism and abstraction. He was also getting engagements on other fronts, very intense engagements with the act of illustration, the complete works of Victor Hugo for one. It would be worth seeing some of those books brought back into print. I’m particularly fond of his illustrations for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, now hard to find.

LOA: An angry political charge runs through all of Ward’s novels. The skyscrapers and factory chimneys loom ominously. The fat capitalists leer and jeer. The oppressed workers suffer. Most unforgettable—in Song Without Words—is the horrific image of the baby on the end of a bayonet with ants crawling over it. Ward is no idealist. The activists get crushed and we get only one hopeful ending. How would you characterize his politics?

Spiegelman: Subtler than its dispersion in that catalog you just gave. He comes by it honestly. His dad, Harry F. Ward, was an important radical Christian in the ’30s, very engaged in trying to right social wrongs. Ward was informed by that. He was not a disengaged illustrator but was in the heat and heart of the action. His name comes up in books that start looking at the radical politics of the period and how it functions. Although he was not a communist per se, he was—and I say this with no pejorative intent—a fellow traveler. I think his politics informs his work and his work informs his politics. I find this one of the most admirable aspects of Ward the man. That picture of the baby on the bayonet is one I have reservations about. He was well-intentioned. But contrast that with the subtlety of the depiction of the capitalist in Vertigo. That work comes alive to us at a time when American corporate mouthpieces inform our daily lives with a brutality that is very reminiscent of the Depression. This doesn’t seem like a period piece; it seems like a clarification.

LOA: In your introduction you quote from Ward’s essay in The Horn Book where he talks about artists needing to have a balance between formal qualities in visual expression and having something to say. Would you say that his achievement has more to do with how he expresses himself than in what he has to say?

Spiegelman: If I had to own only some of his books, if I was making a backpack and wasn’t going to see my bookshelves for a year, I would take Vertigo and Wild Pilgrimage as my desert-island books because they combine both aspects of what he does. But I don’t know that it’s a matter of form and content as separate roads. As always they’re bound up inside each other. What makes him worthy of our attention right now is the redefinition of the book. Very specifically, the way I found my way into Ward had to do with coming to understand with some anxiety how to be a culture worker with pictures without falling into the “beneath contempt” category. More and more art has involved—being considered an artiste has involved—leaving behind linear narrative. And linear narrative has been left to the illustrators and comic book artists.

Now that the comic book itself has been given a new name—not by me, and I’m not even sure I like it as a name—but now that it’s called a graphic novel it becomes clear how Lynd Ward’s work fits into the warped terrain between words and pictures. Comics are no longer kids’ stuff and are a category of entertainment that one can now contend with as an artist. When Ward’s work first appeared, no reviewer mentioned any connection to comics. He had no signifiers, no thought bubbles, no exaggeration. His work was viewed as being totally within the tradition of the book and bookish storytelling. The vocabulary of comics developed around Mutt and Jeff and ultimately the adventure comics that followed, and yet now Ward and comics sit very fully inside what’s become called the graphic novel and sometimes is also known as “ambitious comics.”

LOA: In his survey Wordless Books David Beronä tells the story of when Thomas Mann was asked what motion picture had made the greatest impression on him, he responded Passionate Journey, which of course is not a movie at all but a 1919 novel in woodcuts by Masereel. This speaks to how popular and influential this genre of books was at one time—and then it just seemed to evaporate by the end of the ’40s. What do you think happened?

Spiegelman: In a word, talkies happened. These novels without words were an interesting subgenre. They flourished very briefly in the ‘30s mostly, then only sporadically after that. But this subgenre wasn’t an easy place to create any large body of work, especially because after Ward’s first novel they didn’t have as much of an impact. Even for Ward, his work was received well critically but the sales weren’t impressive. It was a very specific zone where amazing achievement happened. Each of the artists who entered that territory brought something different to it. Milt Gross’s parody of Ward—He Done Her Wrong, published in 1930—was in some ways the most subtle. It’s great now to see these works re-enfolded into one’s notion of what storytelling and bookmaking is.

LOA: When did you first discover Lynd Ward?

Spiegelman: The exact moment I can’t be sure of, but I think I really became aware of him shortly after a couple of his books were reissued in 1967. They were very much a part of my exploring what the limits of comics could be and my thinking about what I wanted to do. He was at one outpost and that outpost doesn’t feel as shabby a red-light district as it once did. Oddly enough I discovered the Milt Gross parody of Ward before I discovered Ward.

LOA: The “Prisoner on the Hell Planet” section in your book Breakdowns is strikingly similar in style to Ward’s work—or certainly to German Expressionism. Was it Ward who influenced you directly or the artists who influenced him?

Spiegelman: Both are true. I had seen Ward’s work and was as informed by the artists surrounding Ward and who influenced Ward as I was by Ward himself. As I explored this world on the other side of high and low art I found that the first artists I was willing to embrace were the German expressionists and objectivists. The artists who had a family resemblance to the kind of art I was trying to make were artists like Max Beckmann and George Grosz.

LOA: Do you have any favorite plates in the books?

Spiegelman: Yeah. In Gods’ Man the picture where the artist is walking alone with shadows flooding the street all around and he is looking grief stricken—that’s a very powerful visual composition. Another that comes to mind is the picture in Gods’ Man when the artist is being fêted and toasted to with raised glasses. It has an ominous quality even as it shows the dramatic moment of success. That picture sits as the best expression of itself one could hope for. There’s a picture of a lynching in Wild Pilgrimage that’s pretty harrowing. And the sequence of images, the dream life of Moloch, is really where Wild Pilgrimage comes to life. That section was very influential for Allen Ginsberg when he was writing “Howl.”

LOA: What can today’s artists learn from Lynd Ward? Are there artists working now who you think are carrying on Ward’s legacy?

Spiegelman: He’s been an influence on a number of artists. Eric Drooker very consciously and specifically. Dennis Cooper has published books without words, very specifically inspired by Ward. There’s an artist named David Holzman who has been working in woodcuts and exploring where those limitations have taken him. Also very interesting to me is a book called The Arrival, by Shaun Tan. It borrows more from the ambitions of Ward than it does from other graphic novels. It’s a surreal documentary that tells of the immigrant experience but with imagery that is not necessarily naturalistic. He is working with pencil, not woodcuts, but his work shows that the power of Ward’s vocabulary is still alive and well.

LOA: Any final thoughts on Ward as a bookmaker?

Spiegelman: The important thing for me is how Ward’s work now fits into a zone where many publishers are trying to find ways to make pictures with words move on an iPad. This allows one to see the purity of Ward’s understanding of what a book could be. One thing that’s great about the Library of America edition is that it respects the bookmaking aspect of a book. It conforms to what Ward intended, with quite minor concessions. The pleasures that come from holding a book are as great as the pleasures of holding an iPad. You have to learn to look at Ward’s work in order for the meaning to become clear. It’s at least as satisfying a process as touching a screen to see what pops up at you. Ward’s works are rich and they make you realize the ways in which a book can be something unto itself that doesn’t have to do just with information content. His work feels fresh even though it expresses a period style because of the way it interrogates what you are using. The book can be transformed and enhanced by a vocabulary other than one that lets you feel like “Oh, isn’t it great to live in the world of tomorrow?” and yet that doesn’t seem archaic. Ward manages that trick in a book that feels, certainly in Vertigo, like a work that one can really concentrate on and attend to with the visual sophistication that is more and more forced on us as the century rises and turns.