Aeneas in the Underworld by Peter Paul Rubens (Public Domain), Sylvia Plath at her typewriter (Smith College), and Orphée perd Eurydice pour la deuxième fois by Benjamin Zix (Public Domain)

Few posthumous literary reputations burn as brightly as Sylvia Plath’s. In her brief life, cut short by suicide at age thirty, she produced a body of work whose incendiary and beautiful language continues to blaze a trail for contemporary readers who are drawn to her searing honesty, vivid emotion, and gift for gut-punching imagery.

But while much has been made of Plath’s tumultuous personal life, her greatest art sprung not from madness or untamed anger, but from a deep firsthand engagement with the trials, travails, and daily denigrations suffered by women. Combining this rich vein of experience—motherhood, marriage, misogyny—with a thrilling, often shocking and hilarious, poetic imagination, Plath transcends the confessional label, becoming, in the words of author and translator Sarah Ruden, a “mythmaker,” capable of speaking the unspeakable and enlarging the personal sphere to universal dimensions.

In I Am the Arrow: The Life & Art of Sylvia Plath in Six Poems, Ruden analyzes Plath’s legend and enduring fame through close readings of half a dozen of her most brilliant pieces, arguing for the writer’s establishment “on purely literary merit, in the cool mainstream of literary greatness.” Below, Ruden discusses the misapprehensions that have plagued Plath’s legacy and shares a fresh perspective on interpreting this adored if widely misunderstood icon of American letters.

LOA: In your introduction, you contend that Plath can be understood as a mythological figure. Can you say more about this interpretation of her legacy and accomplishment?

Sarah Ruden: I’m a Classicist by training and partly by profession (most of my translations are of ancient Greek and Roman authors), so I naturally try to place Plath in a very long literary tradition. But I hope I don’t give the impression that I think she was like me in her interests or calling: she was in fact intensely, competitively focused on contemporary literature, and I’m not. She was keenly aware of which hot poets were publishing in which hot magazines, which were getting grants and jobs and other perks, and who might help her, whereas that’s a complete blank to me. I wrote a book about this twentieth-century poet only because I thought that the work of her final three years rises above all that gamesmanship.

Sylvia Plath in Paris, 1956 (Indiana University)

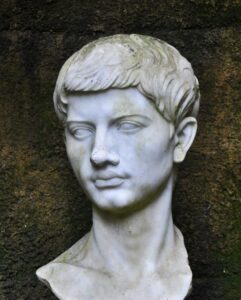

But where my background does seem to give me insight into Plath is in the ancient world’s examples of the powerful dynamic of identification between great authors and their audiences. There have actually been very few authors in history onto whom readers glom with such a passion as they do onto Plath. One such author was Vergil: people would chase him down the street when he showed up in Rome, and Vergil’s patron, the first Roman emperor Augustus, took such a heavy-handed, controlling interest in the Aeneid’s composition that Vergil claimed he could complete the epic poem only while traveling through the other side of the known world. He ran away, but Augustus tracked him down, and there was a confrontation that may have contributed to Vergil’s death shortly afterwards.

In part, this literary stalking, this controlling pressure that readers can put on a body of literature because they love it so much, has to do with that literature’s beauty and charm, with the sense that the author has put something on display for which obsessive attention is natural and proper. Vergil’s Latin poetry is stunning, a revelation for the Romans who were used to mediocre adaptations from Greek works. Certainly the aesthetics of Plath’s work are very striking. She took free verse, which always risks being prosaic and dull, and jazzed it up with crazy effects of sound and imagery; she was like T. S. Eliot, but she didn’t hide behind esoteric, coy allusiveness and gestures of withdrawal that can feel like affectations.

Bust of Vergil at his crypt in Naples (Public Domain)

The sheer beauty of her work pulls people in, but she also gives the sense of revealing ultimate secrets, of being fearlessly in touch with what is most painful and destructive in life, and yet overcoming it with her fearless frankness. This is what I mean, broadly, when I talk about the author or the author’s persona as the hero resurrected from the underworld after immense loss and pain. Vergil pulls this scenario off in his tale of Orpheus and Eurydice in the Georgics: Orpheus loses his beloved to a second death, and he is dismembered and killed himself, but his severed head floats down the river crying Eurydice’s name: his tuneful voice survives with its message of love that does not die. In the Aeneid, Aeneas makes the perilous and excruciating journey to Hades, but he re-emerges with revelations guiding the world’s destiny for ages to come.

I don’t subscribe to the bitch-goddess or inspired-madwoman theory of Plath’s literary flowering in the fall of 1962 and the winter of 1963, right before her suicide; this theory insists that her genius is closely connected to wild rage and self-destruction. Bull.

Plath makes this pilgrimage in the name of women. She descends to a place normally too shameful and full of despair to speak of—the female hell of utter rejection and failure, both as a wife and as a public voice—but she is resurrected in the posthumous fame of her work, giving voice to things that women in general can affirm as true. No other woman writer, no matter how talented or original, makes this kind of harrowing journey; all of them mitigate, soften, equivocate the big truths of women’s lives; none of them affirms the depths of contempt and neglect that women commonly experience, or the immortality that they gain only through sacrifice of the self.

LOA: Throughout I Am the Arrow, you interrogate the attention paid to Plath’s biography in lieu of her literary achievement on its own terms. How has fascination with Plath’s life story distracted from her poetic gifts?

SR: I’m not sure that the distraction was ever avoidable, so I don’t want to deplore it or pooh-pooh it. In fact, the preoccupation with Plath biography is both natural and fruitful. This is an intensely autobiographical author, so how would you consider her work apart from her life? And the story of her life has also been bound up with the struggle to preserve, appreciate, and propagate her greatest work. Just to cite the most important instance of this, the first version of her poetic masterpiece, the Ariel collection, was distorted because it was edited and published after her suicide by Ted Hughes, the husband who had vilified her, cheated on her, and walked out on her and their children, a man who during her literary afterlife was more inclined toward his own self-justification than celebrating her genius.

Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath in 1956 (Brittanica)

So how would a devotee of Plath like me separate interest in this relationship from a commitment to helping other people discover Plath’s work and enjoy it more fully? If I didn’t research the relationship and try to understand its aftermath better, I wouldn’t even know about the long-term damage to Plath’s reputation that needs repairing. Besides, there is instinctive, irrepressible curiosity, which you don’t have to be an active advocate of Plath’s work to feel. She died very young, at the age of thirty; there is an intrinsic sense that the work is incomplete, and an urge to seek more information from biography.

Where I think that biographical considerations detract from a just appreciation of Plath’s poetry is in the propensity to get obsessed, enraged, almost to act as if she were still alive and we could save her by heroic personal advocacy. I write in the book about how I fall into that trap myself: as an example, I was fuming over a crap summer job that Plath had as a college student, and I was researching the employer’s underpayment of Plath, and telling myself that people can sue for that, and comparing a crap summer job I was offered as a student but turned down.

This attitude is a fundamental betrayal of Plath’s genius. Plath is dead, and all our personal attention and defense and nurture can’t make her any less dead. But the poems are alive, and more alive the more we explore and share them. This is why I devote so much of the book to close reading, to the description of the smart, moving, hilarious, insightful, musical, gorgeous things the words of the poems do, line by line.

Sylvia Plath and Elizabeth Cantor on Cape Cod, 1952 (Smith College)

LOA: How did you decide which poems to include in this volume? Which works narrowly missed the cut?

SR: It was a tough set of decisions. But I ended up just choosing the poems I like the most, even though “The Babysitters” is far less famous and, along with “Mushrooms” and “You’re,” falls outside of the searing, prolific period of writing near the end of Plath’s life that gave us the best-known Ariel poems with their surreal rage, flights of transcendence, and deep despair. Representing that period are only three of my selections: “The Applicant,” “Ariel,” and “Edge.”

All and all, this is an unusual as well as a small collection of Plath poems, so my choices need an explanation. I don’t subscribe to the bitch-goddess or inspired-madwoman theory of Plath’s literary flowering in the fall of 1962 and the winter of 1963, right before her suicide; this theory insists that her genius is closely connected to wild rage and self-destruction.

Bull. For one, that’s a condescending and misogynist way of looking at her achievement; for another, it could hardly be borne out by any objective critical consideration of the late poems as a group. It seems to me that, whenever Plath was off her head—say, in drinking too much, in desperately trying to repair her relationship with the husband who clearly wanted her gone, in trying to force him back with frenetic expressions of rage, or in flailing around for help that people smugly begrudged her because she was an uppity American woman living in post-war Britain—the poems she wrote were out of control and bad.

“The Jailor,” for example, isn’t an imaginative, thoughtful, ironic poem about a doomed marital relationship, as “The Applicant” is—that’s a poem in which Plath coolly considers the female role in dehumanization. Ted Hughes wasn’t a jailer, rapist, or torturer, and the premise that he was making Plath stay is false: he in fact went to great lengths to get rid of her; falseness shows in the poem’s shrillness, in its lack of interesting movement. “Daddy” is, musically and dramatically, a brilliant poem, but it’s in bad taste; it’s offensive, lumping unresolved mourning for a father and a marriage in with the Holocaust, because the author’s rage is out of control.

In the end, I decided to make strong-minded choices among the late poems as well as the earlier ones, and I found that what I really wanted was three late ones and three considerably earlier ones.

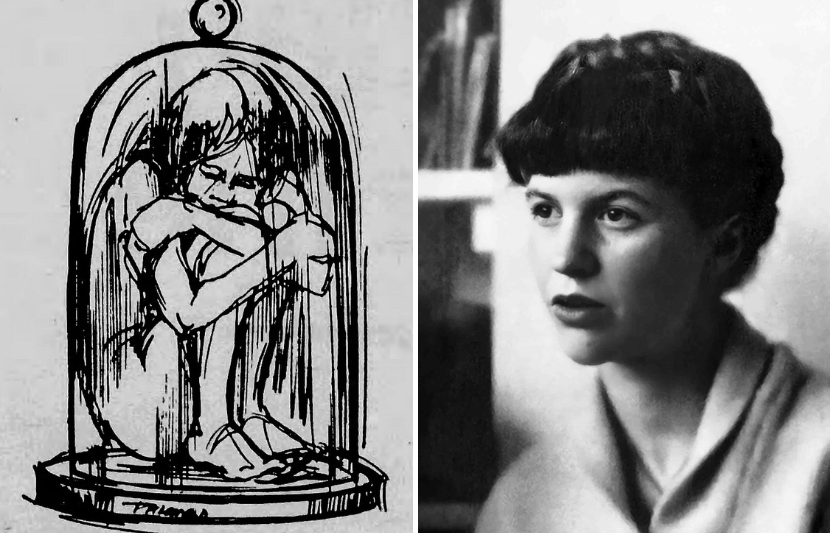

1971 illustration of The Bell Jar (Cincinnati Post / Public Domain) and portrait of Sylvia Plath in 1963 (Public Domain)

LOA: Plath’s copious journals and correspondence, not to mention her semi-autobiographical novel The Bell Jar, provide fascinating counterpoints to the poems. How did you draw on Plath’s non-poetic writings for this book?

SR: The Bell Jar is illuminating in many ways for reading the poetry, but one of my favorite connections is humor. Plath had a gift for punchy, sardonic, colloquial language, like “miraculous fur piece” in The Bell Jar, a phrase that distills the greed and hype of Madison Avenue perfectly. Similar to this phrase is the sales patter in “The Applicant”: “Believe me, they’ll bury you in it,” “A living doll, everywhere you look,” and so on.

Plath’s honing of words for the absolute right effect, which is the essence of humor, belies the slander that she only achieved her artistic height when, right near the end of her life, she ran amok and alienated all the sane people around her—just like an over-emotional, unstable woman! In reality, she was in exquisite control in writing the poems “Edge” and “Balloons” just six days before her death. In her best writing she was a professional, a performer, a craftswoman to the last, as rhetorically powerful when she was abandoned by her husband and shivering during the worst weather in decades and overwhelmed with the sole care of two tiny children and approaching the decision to gas herself as she was many months earlier, when she confidently wrote The Bell Jar with the help of a lucrative grant, spending whole mornings typing away in a nice borrowed apartment while her helpful husband minded the baby at home.

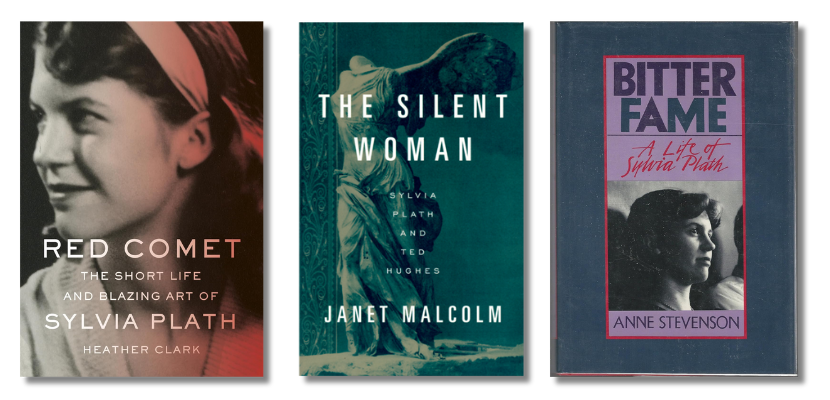

LOA: In addition to Plath’s own extensive writings across genres, there is a vast archive of writing about Plath: biographies such as Heather Clark’s Red Comet and Anne Stevenson’s Bitter Fame, interpretive nonfiction like Janet Malcolm’s The Silent Woman, and many others. Where would you direct curious readers interested in learning more about Plath?

SR: Don’t read Bitter Fame, unless you want to walk around for weeks cursing to yourself. The book is a contrivance of the Plath estate at its worst. Poor Anne Stevenson, the author, was lured in with a big advance and then forced to endure Olwyn Hughes, Ted’s creepy sister, as an effective co-author. Bitter Fame has, for example, an appendix memoir in which a misogynist and anti-American hostess reviles Plath for eating heartily when she was pregnant. Malcolm and Clark, on the other hand, are superb, especially Clark.

Books on Plath: Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath by Heather Clark, The Silent Woman by Janet Malcolm, and Bitter Fame by Anne Stevenson

Perhaps the biggest challenge is the sheer proliferation of writing and other commentary about Plath over the years. I wouldn’t call much of it bad, but a lot is rather trivially personal. In particular, I think it’s a sad commentary on the status of women that such an important woman writer gets treated reputationally as if she were a plump carcass lying on the Serengeti for the gnawing of all beasts, but with the most aggressive given priority.

For instance, a fellow student with whom Plath traveled, and who, allegedly without meaning to, locked her out of their room and failed to respond to her pounding on the door, gets all oh-so-disturbing-to-poor-me about Plath’s anger at having nowhere to sleep in a strange city—in fact, this author writes a whole memoir with the theme of Plath’s bad temper. A male author has to stab his wife or drink himself to death to earn as much opprobrium.

But I think that by this point in time it can all be taken as an educational and entertaining phantasmagoria. The triviality and wrong-headedness and meanness of spirit assume their proper proportion when set against the steady growth in appreciation of Plath as an exponent of women’s enduring existential challenges, and as an author who is breathtakingly fun and moving to read.

Sarah Ruden has translated Vergil’s Aeneid, Aristophanes’s Lysistrata, Augustine’s Confessions, and other works, and has published books about the Bible (Paul among the People and The Face of Water) and a biography of Vergil. Her biography of the martyr Perpetua is forthcoming from Yale University Press and Reproductive Wrongs: A Short History of Bad Ideas, her survey of writing against reproductive choice since the Roman Empire, is forthcoming from W. W. Norton.