American infantryman of the 82nd Airborne in Belgium, December 1944 (Public Domain)

For all the books, films, and other media made to commemorate it, there remains much to discover about the European Theater of World War II. Embedded within the popular memory of such epochal events as D-Day and the Battle of the Bulge were millions of individual stories, ranging from the frontline exploits of soldiers to the air war experienced by pilots and crew in the skies over Germany to the tireless efforts of noncombatants sustaining the push for Allied victory.

In the just-published World War II Memoirs: The European Theater, five writers with vastly different perspectives on the conflict enlarge our understanding of what it meant to serve and fight. With honesty, artistry, and insight, they spotlight moments both intimate and strange, tragic and triumphant, illuminating the complex human dimension of this global conflagration.

Below, volume editor Elizabeth D. Samet, professor of English at West Point and editor of the previously released World War II Memoirs: The Pacific Theater, reflects on her work assembling the new anthology, discusses the salient differences between memoir and history, and examines the role of subjectivity and authority when it comes to crafting a nuanced tapestry of life in extraordinary times.

(The views expressed in this interview do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.)

LOA: Why did you choose these five memoirs for this volume out of the hundreds to emerge from the war in Europe?

Elizabeth D. Samet: You’ve hit on one of the great challenges of any collection like this: there are so many wonderful options from which to choose. The idea behind this volume was to include a range of voices.

We are accustomed to thinking about war and memory in very restrictive ways encouraged by military organization and culture: “When you call a company a rifle company,” declares Charles B. MacDonald in the preface to Company Commander, the first selection in this volume, “you are speaking of the men who actually fight wars.”

MacDonald is attempting to distinguish the infantry, those soldiers most likely to engage the enemy at close quarters, from all those military personnel who are doing something else. Obviously the foot soldier is a central participant in the story, without whom wars, notwithstanding technological revolutions in weaponry, still cannot be fought. But dismissing all the rest closes us off from the various ways in which people experience war. It also implies that a large swath of those who serve in uniform—infantry made up less than fifteen percent of American troops serving abroad in World War II—have little to offer by way of insight. That is very far from the truth.

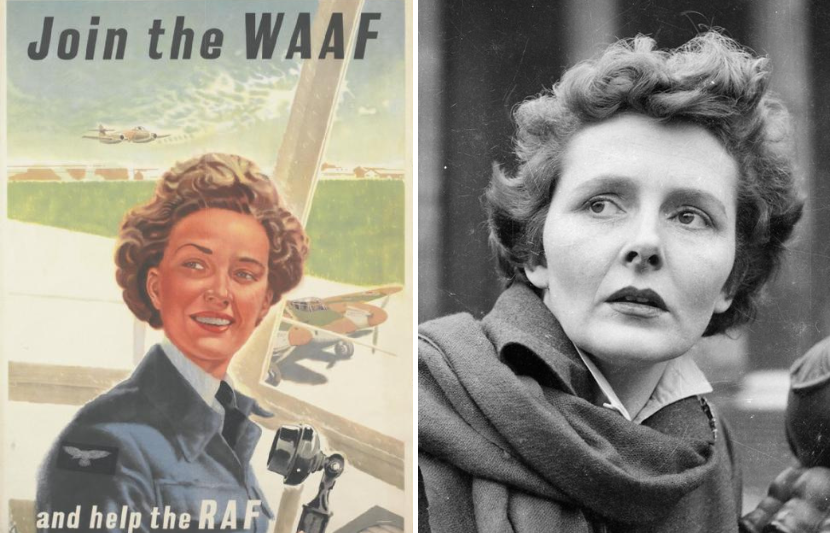

In this volume we have collected an account of the air war and an assessment of strategic bombing in Elmer Bendiner’s The Fall of Fortresses; a counterintelligence officer’s wartime journal contextualized within a philosophical meditation on the nature of war itself in J. Glenn Gray’s The Warriors; and the reflections of a radio telephone operator with the British RAF in Mary Lee Settle’s All the Brave Promises.

We also have a second infantryman’s account of the war: James Harden Daugherty’s The Buffalo Saga, which recounts the author’s service with the only African American infantry division in the European Theater. Daugherty does indeed fit MacDonald’s exclusive definition of “the men who actually fight wars,” yet the experiences of African American soldiers in a segregated army in which race prejudice ran deep has too long been neglected.

A Black soldier of the 12th Armored Division stands guard over a group of Nazi prisoners, April 1945 (Public Domain)

LOA: Popular American memory of World War II tends to see the conflict as a series of epochal events directed by major historical figures. But as evidenced in these memoirs, the experiences of frontline soldiers, airmen, and behind-the-lines personnel were often isolated, fragmentary, and disconnected from any sense of a “big picture.” How great is the gap between the “top-down” history that helps us make sense of events retrospectively and the unmediated experiences of individuals caught up in the uncertainty, fear, and boredom of war?

EDS: I think the popular focus on military and civilian leaders—an expression of the so-called “Great Man” theory of history—springs from a natural desire to impose order on a sprawling, chaotic phenomenon. The reflections of those further down the chain of command complement the dramas of opposing generals and help us to understand that no two experiences of war are the same. It is nearly impossible to consider the end game when one’s focus is on surviving until tomorrow.

The more memoirs one reads—civilian memoirs are crucial, too—the richer and more nuanced the tapestry appears. In the specific case of World War II, so often called “the Good War,” these memoirs force us to come to terms with what it means to call a war “good.”

LOA: Each of these memoirs has a distinct literary style. Charles B. MacDonald, for example, aspires to record his service through straightforward and truthful reporting (“to make a story of war authentic you must see a war,” he writes in his preface). J. Glenn Gray, meanwhile, approaches his subject more philosophically, extracting meaning from both his wartime memories and journals and his postwar reading, and Mary Lee Settle offers a novelist’s impressionistic memories of her RAF service. What do these differing approaches tell us about the war memoir as a literary genre?

Postwar poster for joining the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (Imperial War Museum) and photo of Mary Lee Settle (The Paris Review)

EDS: While these five selections certainly differ stylistically, I think they share a compulsion to reveal personal truths, set a record straight, or tell a story that would not otherwise be heard.

I find MacDonald’s definition of authenticity a bit restrictive; being an eyewitness is no guarantee of authenticity or of the ability to transform raw experience in an account legible to a wide array of readers. Memory deceives us even in pacific times; in wartime, its slippery tricks are even more potent.

Writers and readers of memoir enter into a kind of pact that at once acknowledges the fickleness of memory and the overriding desire to illuminate an experiential truth. The roots of autobiographical writing in war—think of Xenophon’s Anabasis or Caesar’s Gallic War—are important to an understanding of the genre’s navigation of subjectivity. Memoir is not history.

It may seem strange to say, but so much of wartime is removed from the battlefield yet not from dislocation, violence, hardship, and chaos.

LOA: You also edited World War II Memoirs: The Pacific Theater for Library of America. What are the differences between the war in the Pacific and in Europe that stand out when comparing memoirs from the different theaters?

EDS: The three memoirs collected in The Pacific Theater are like old friends to me. I have known about and been fond of them for a long time. Their authors, E. B. Sledge, Samuel Hynes, and Alvin Kernan all became college professors—perhaps there’s a natural feeling of kinship in that—and their masterly balance of visceral immediacy with tranquil reflection strikes me as a product of training.

J. Glenn Gray is the only academic in the European Theater volume, and I think the vocational diversity on offer here—journalist (Bendiner), civil servant (Daugherty), novelist (Settle), and official military historian (MacDonald)—gives this volume a different flavor. I’m excited by the way they interact—unexpected ingredients that somehow cohere.

LOA: The writers of these memoirs grapple in different ways with the moral cost of war, reckoning with the effects on the individual of witnessing and perpetrating violence. (Gray writes: “I began to detect with a kind of horror that I was becoming inured to cruelty and not above practicing it myself on occasion.”) There is also, in Daugherty’s memoir, the complexity of fighting for a country in which you are not treated as a citizen: “I am a Black American,” he writes. “This meant that I must fight for a country that regarded me as an individual with no rights in the United States of America that white Americans were bound to respect.” How do these writers navigate the ethical territory of conflict?

EDS: Ethical questions are paramount for Gray, who was a philosopher after all. And I think Daugherty offers powerful insight into the paradox of serving in an army that was said to be fighting for freedom when one’s own freedom was such a severely curtailed thing.

Bendiner’s discussion of strategic bombing, a program that has become quite controversial in retrospect, also inevitably focuses us on the ethical dimensions of “total war.”

Clockwise from left: B-17s conducting bombing runs over Hungary and Czechoslovakia in 1944, and a German pilot bailing out of his fighter plane (Public Domain)

More obliquely, Settle’s service with British forces helps us to remember that the rest of the world had been at war since September 1939 by the time United States officially joined in December 1941, more than two years later. Settle’s book is a useful corrective to today’s somewhat distorted sense of national motivations at the time, and we fail to remember the indifference of many Americans toward European freedom and especially toward the fate of the world’s Jews.

LOA: Settle writes: “For every ‘historic’ event, there were thousands of unknown, plodding people, caught up in a deadening authority, learning to survive by keeping quiet, by ‘getting by,’ by existing in secret, underground; conscripted, shunted, numbered.” How can accounts from these “unknown” participants—some of them women—fill out our picture of the war and its participants? What do their stories tell us about a wartime removed from scenes of battle?

EDS: It may seem strange to say, but so much of wartime is removed from the battlefield yet not from dislocation, violence, hardship, and chaos. That’s what MacDonald’s focus on the infantry soldier, essential as it is, largely passes over. Think of the vast numbers of people whose lives were irrevocably transformed by mass mobilization, by unprecedented extensions of state power, by the various indignities the state imposed on those (in large part) conscripted to do its most unglamorous work.

That’s one of the things these memoirs, especially Settle’s and Daugherty’s, demand that we ponder. These works reveal something of the ways in which modern states exercise power, and that’s something that extends beyond war per se.

Three Americans of the 117th Infantry Regiment, 30th Division, prepare to enter a house where enemy snipers are holding out, Belgium, 1944 (Public Domain)

LOA: Several of the memoirists identify an inherent “strangeness” to war. Gray writes, “I think every soldier must have felt at times that this or that happening fitted into nothing that had gone before; it was incomprehensible, either absurd or mysterious or both.” Bendiner, meanwhile, compares a B-17 mission to attending a movie: “It was as if we were in a soundproof chamber beyond which the enemy whirled as in a silent cinema.” What can readers make of this unreal or uncanny side of war?

EDS: I think the surreality of war is, to a degree, a byproduct of the rhythm of long stretches of boredom punctuated by intense bursts of violent action that characterizes war experience. The role of chance, which is a feature common to personal memoirs, fictional treatments, even treatises on war, also helps to create the conditions for surreal collisions of the kind Bendiner and Gray describe.

LOA: Where can readers intrigued by these memoirs turn next? What other accounts of World War II—autobiographical, historical, or fictional—help us understand this great conflict, now rapidly receding from living memory?

EDS: Because we have for a long time neglected the Pacific Theater in favor of the European, I think there’s a mistaken belief that we really know the latter. We may know something of a part of it, but the hundreds of available memoirs suggest that there is still a great deal for us to learn.

Standouts for me include Victor Brombert’s Trains of Thought, Charles W. Dryden’s A-Train: Memoirs of a Tuskegee Airman, Paul Fussell’s Doing Battle, Betty Lussier’s The Intrepid Woman, and John Muirhead’s Those Who Fall. Readers will find these and other titles catalogued in my introduction to the volume, where I suggest a way to follow the American campaigns in the Mediterranean and European theaters by reading several excellent memoirs in sequence.

American soldiers in Paris following the liberation of the city by Allied forces in August 1944 (Public Domain)

Elizabeth D. Samet is professor of English at the United States Military Academy at West Point and the author of Willing Obedience: Citizens, Soldiers, and the Progress of Consent in America, 1776–1898; Soldier’s Heart: Reading Literature Through Peace and War at West Point; No Man’s Land: Preparing for War and Peace in Post-9/11 America; and Looking for the Good War: American Amnesia and the Violent Pursuit of Happiness.