Library of America editor Stefanie Peters speaking at the Row House Forum in Lancaster, PA, in November 2024.

This article is adapted from a talk given by Library of America editor Stefanie Peters at the Row House Forum in Lancaster, PA, in November 2024. A second excerpt from this talk, on how and why to read books, can be found on Peters’s Substack.

Uniquely among the nations of the world, the United States was founded on words—the Declaration of Independence, the great debates in the Federalist Papers about what this new nation should look like, and the Constitution itself.

But it took until the 1820s, fifty years later, for a writer to specifically identify themselves as an American writer. That was Washington Irving, the author of “Rip Van Winkle.” After his book The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. was published, he toured France and Great Britain, where he was considered to be something absolutely remarkable: an American who could write well in English.

Indeed, outside of the academy, the idea of a distinctly “American” literature did not really exist among readers until World War II, spurred by the patriotism of the war effort. And still, even after the war, in the late 1950s, the works of many American writers we’d consider indispensable were completely or almost completely out of print and thus largely unavailable to readers.

The work of creating an authoritative text can be likened to the stabilization, cleaning, and restoration of a work of art that has deteriorated over time.

Into this breach stepped American writer and critic Edmund Wilson, who said, “It is absurd that our most read and studied writers should not be available in their entirety in any convenient form.” Cue the Library of America, founded in fulfillment of Wilson’s vision in 1979 with seed funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Ford Foundation.

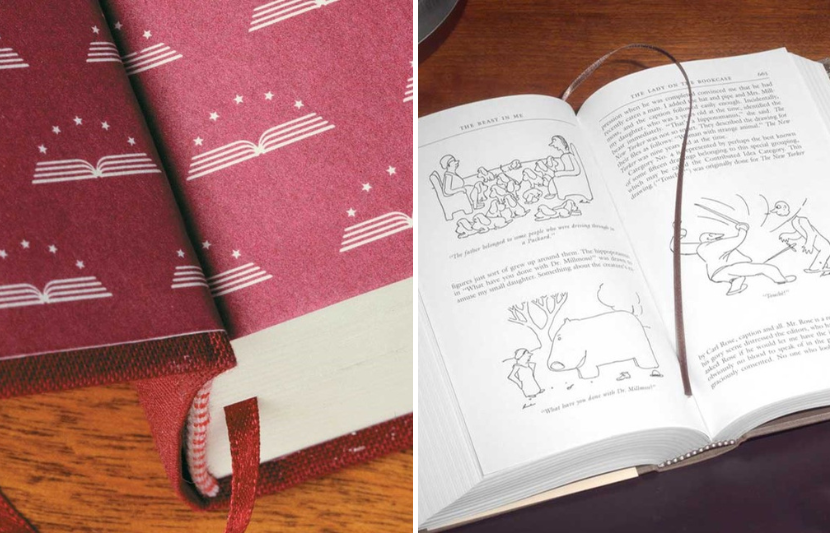

To date Library of America has published over 390 volumes in our series. And these are beautiful books: the size of each volume is based on the golden ratio. The font used is Galliard, which is now in the Museum of Modern Art, and is based on a sixteenth-century typeface by the French printer Robert Granjon. Each volume has a cloth cover and Smyth-sewn binding, which allows the books to lay completely flat when you open them. They are printed on acid-free paper, which means the paper will never turn yellow or brittle. They come with a sewn-in ribbon bookmark. And they have a lovely page layout designed with the experience of the reader in mind.

Library of America editions are clothbound with Smyth-sewn binding and lay completely flat.

But what really distinguishes Library of America is not just keeping these works in print or producing such fine editions, but publishing authoritative texts.

What do I mean by authoritative text? Essentially it is a text that is as close as possible to what the author intended it to be. Lots of things can happen to the text of a book after it leaves the author’s desk: It could be censored or bowdlerized. It could be published without the author’s knowledge or editors might have tinkered with the prose. Reprinters might have introduced typos. Descendants might have made changes to things that might embarrass the family.

Authoritative texts are a way to honor the author’s intentions, and also to ensure that readers have access to the best version of a book available. James L. W. West III, the Fitzgerald scholar who edited The Great Gatsby for Library of America, said that the work of creating an authoritative text “can be likened to the stabilization, cleaning, and restoration of a work of art that has deteriorated over time.”

I’ll give you a few examples from books I have edited.

A Wrinkle in Time

In 2018 we published a boxed set of Madeleine L’Engle’s Kairos novels, which include the Wrinkle in Time quartet and the Polly O’Keefe quartet, about Meg and Calvin’s daughter.

A Wrinkle in Time was published in 1962 and has been continuously in print for the past sixty-plus years. But we know that L’Engle was unhappy with the first edition of the book, because she wrote about it in one of her memoirs. L’Engle had carefully differentiated in her typescript between the human characters and the extra-special, extra-terrestrial three Mrs W’s, by giving Mr. and Mrs. Murray periods in their names and Mrs Who, Mrs Whatsit, and Mrs Which no periods. But a copyeditor had carefully added periods to every single Mrs in the book.

In her memoir, L’Engle called this “the worst thing” the copyeditor had done, which made me wonder if there were other errors. So I compared as many editions as I could. I looked at British editions, previous American editions, the audiobook that L’Engle recorded, and finally discovered that even the current hardcover edition from Farrar, Straus and Giroux has a different text from the current FSG paperback edition. The hardcover has fixed the periods, but also changed Meg’s “grammar-school” to a “grade-school” and Meg’s “blazer” to a “jacket,” while the paperback matches the first-edition text.

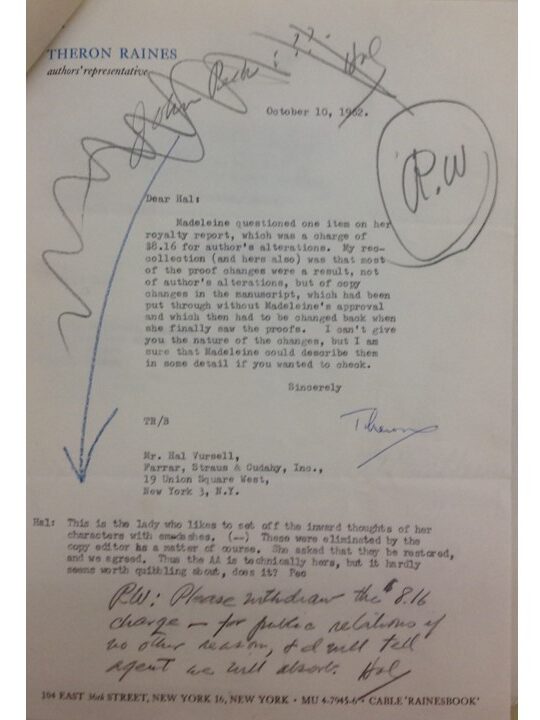

1962 letter from Madeleine L’Engle’s literary agent discussing fees for manuscript revisions (Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library)

I wrote to everyone who worked with L’Engle at her different publishers, and I visited the Farrar, Straus and Giroux records at the New York Public Library. At the library I found a letter from L’Engle’s literary agent from October 1962, showing that L’Engle was charged $8.16 for author’s alterations to the proof pages. So this was proof that she was able to make the corrections she wanted to the text, except the periods. That would have been too expensive to change.

Finally, I contacted L’Engle’s granddaughter Charlotte, who has a lot of her grandmother’s unpublished papers. Charlotte and I examined the four drafts of A Wrinkle in Time that she has, and in the process we found four errors that had never been corrected before, as well as some never-before-seen deleted chapters. We were able to publish these deleted chapters in the LOA edition.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

You may be familiar with Charlotte Perkins Gilman for her short story “The Yellow Wall-Paper,” about a woman who slowly loses her sanity when her husband insists she recuperate in a bedroom with yellow wall-paper. The textual history of this story is so complicated that for this edition, we decided to publish two different versions of the text.

Gilman started submitting the story to magazines in June 1890, and shortly thereafter, she also sent the story to two men: her friend William Dean Howells, who is also published in LOA, and to Henry Willard Austin, who was a literary agent. Howells forwarded the manuscript to the editor of the Atlantic Monthly, who rejected the story in October with the note: “Mr. Howells has handed me this story. I could not forgive myself if I made others as miserable as I have made myself!”

The story was published in the January 1892 issue of The New England Magazine. However, Gilman seems not to have known that the story was accepted until she saw it in the magazine. She wrote to the editor asking whether they were going to pay her, and was told that Austin had been paid as her agent, which Austin denied.

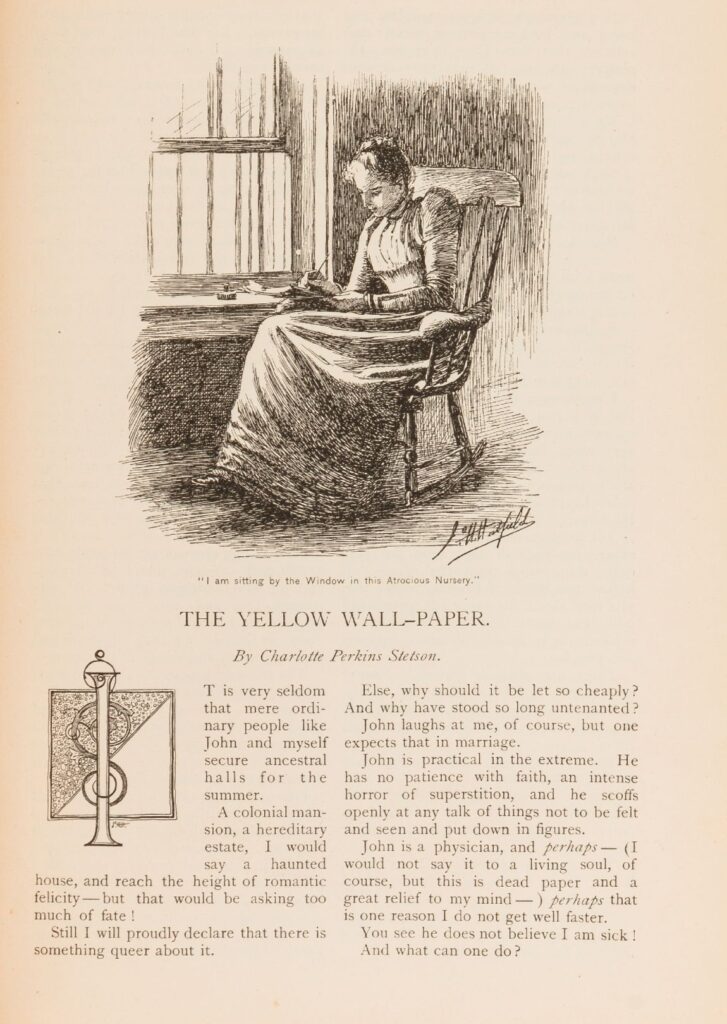

“The Yellow Wall-Paper” as it appeared in an 1892 issue of The New England Magazine, published under Gilman’s married name “Stetson” (Biblio.com)

Now this story is strange for several reasons. The New England Magazine had already published work by Gilman. One of the editors of the magazine was her uncle, and Howells later claimed that he was the one to have “corrupted the editor of The New England Magazine into publishing” the story. So it’s odd that she didn’t know it was going to be published.

Then, seven years later, a book publisher decided to bring the story out as a book. Gilman was in England at the time, and so wasn’t involved in its publication either, although presumably she could have sent them a corrected manuscript. But they reprinted the magazine text.

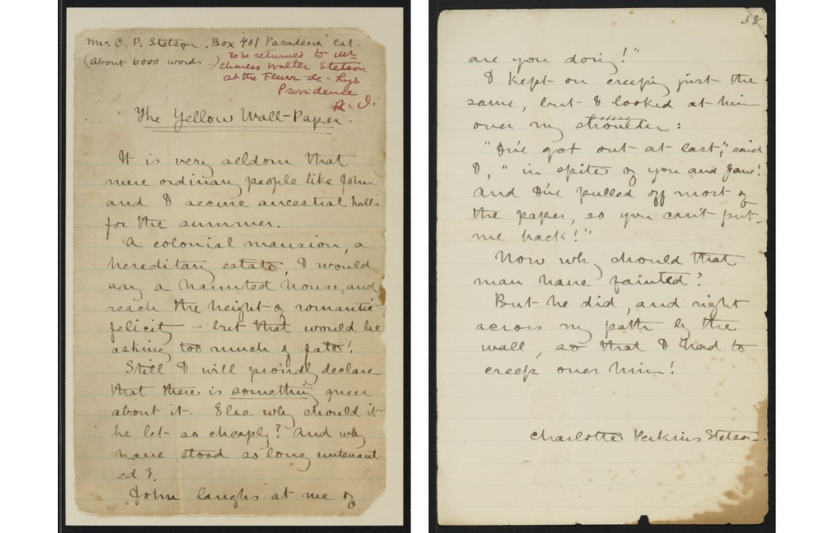

Why is that important? Gilman’s manuscript of the story still exists, and there are hundreds of differences between her manuscript and the published story. The published version often joins separate paragraphs together, which has the effect of making the narrator seem saner than she is until the end of the story. And the biggest change is to the final sentence: the manuscript says, “Now why should that man have fainted? But he did, and right across my path by the wall, so that I had to crawl over him!” The magazine version added two words to the end: “every time,” suggesting that the woman is never able to leave the room and the nightmare she’s trapped in.

Handwritten manuscript pages of “The Yellow Wall-Paper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute at Harvard University)

There’s really no way to know exactly what happened with the publication of this story, who made the edits, and how much Gilman knew, so we chose to publish both versions so that readers can experience the story both ways.

Wendell Berry

I often joke that I mostly work with dead writers. Wendell Berry is one of two writers I’ve had the privilege of working with while they’re living. Wendell just turned ninety in August and he’s still writing.

I’ve had the joy and honor of publishing two books with Wendell so far: two volumes collecting his Port William novels and stories, the first published in 2018, and the second just published in July.

With a living author like Wendell Berry, the question of an authoritative text becomes a bit easier. We publish the version of the text that Wendell wants us to. But there still is a process to get there. One reason why is that Wendell tends to revise his books even after they are published.

Wendell’s books are first published by Counterpoint, and he has been working with his editor there, Jack Shoemaker, for over sixty years. His first three novels were published before he met Jack, and then in the 1980s and ’90s they were reissued by Counterpoint, and Wendell revised them pretty significantly for their reissue. In Nathan Coulter, Port William was never named in the first edition, and Wendell completely deleted the last chapter for the revised edition. The revised A Place on Earth is about one-third shorter than the original edition. And when The Memory of Old Jack was reissued, Wendell added an author’s note explaining the changes he’d made that said, “When I began to write about the people of the imagined community of Port William in 1955, I had no idea that I would still be writing about them in 1999. I had no plan, and I still don’t.” The note also owned up to “‘errors’ of genealogy and geography.”

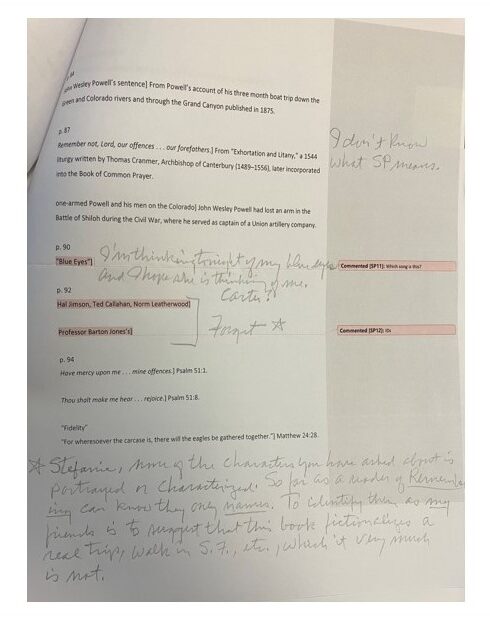

So when I come to edit Wendell’s books, I start by getting the most up-to-date versions of the texts from Jack. Then, I become something like a fact-checker. I send Wendell letters with lists of questions to create the explanatory endnotes that go in the back of the Library of America editions, as well as any typos or errors in the texts I either find or suspect. A few weeks later, I get back careful, handwritten explanations and sometimes further edits. Here’s a draft I sent Wendell of some of the endnotes with questions in pink, and you can see his answers to me in pencil.

Draft of endnotes for Wendell Berry: Port William Novels & Stories (The Civil War to World War II) showing Berry’s handwritten comments.

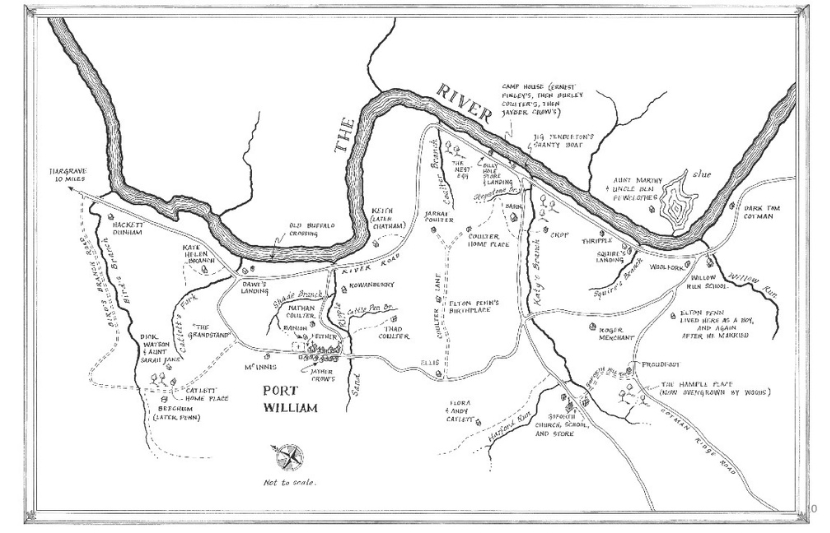

For example, for the volume of the postwar novels and stories that came out in July, I wanted to know why, in The Memory of Old Jack, Jack Beechum hears the song “Wildwood Flower” at a dance in 1888, when the first recording I could find by that title was from 1928 by the folk group the Carter Family. I was convinced I had the wrong song! But it turns out I caught Wendell in an accidental anachronism, and he revised the sentence so that it doesn’t name the song. Wendell also sent me a handful of corrections, including changing the name of Wheeler Catlett’s boss in Remembering, changing Dorie Catlett’s death date in the family tree, and moving the location of the Stepstone Bridge on the map of Port William.

Map of Port William, KY.

At Library of America, we like to think about the books we preserve as being the important voices in a four-century-long national conversation. Who are the voices we need in that conversation about American identity, culture, and history? What are the writings that are our shared birthright, our shared heritage as a nation? That help us see what we have in common as Americans?

Robert Frost said “America is hard to see.” We need the voices of the best American writers to help us see who we are as a nation, where we’ve been, and where we’re going. That’s going to be a democratic conversation, a multi-vocal conversation, often a raucous conversation.

We need the voices of: our past presidents, of James Baldwin, speaking for human equality and civil rights. The suffragists, reminding us that there were still female citizens of this country who couldn’t vote up until 1965. Our editions of African American and Latino poetry, showing how rich, powerful, and central these poets have been to centuries of the American poetic tradition. We need the science fiction writers, the crime and mystery writers, the environmental writers, and the writings of the soldiers and reporters who witnessed the Civil War, both world wars, and the Vietnam War.

Those are just a few. Library of America tries to make all these voices more visible.