Truman Capote in 1948 (Carl Van Vechten / Library of Congress)

To celebrate Truman Capote’s centennial this September, we’re excited to share this appreciation of his remarkable oeuvre by author Robert Pranzatelli.

by Robert Pranzatelli

One spring afternoon in the late 1980s, I sat at a large wooden table in the New York Public Library, in a room dedicated to rare holdings, and looked through a number of Truman Capote’s holograph manuscripts, notebooks, and typed drafts. I had gained admission through tact and a bookish appearance, with no scholarly credentials, to see for myself what tidbits of the late author’s unpublished work might await discovery. There weren’t many, but to handle the pages on which my favorite writer had written his sentences gave me a new and subtle satisfaction.

One pearl I did find was an abandoned fragment, a sort of prose poem about Eastern Long Island, where Capote had lived for the last twenty years of his life. In two lovely paragraphs he stated his preference for

that moment when the light goes yellow, that late October moving to November moment when the light of ocean-salted afternoons coldly burns like the drifting gold of dying leaves. Then overhead wild geese! – herds honking southward in loosely waving lines. Wild geese and wild duck; and wild swans undulating on the darkening ponds that flicker among the potato fields.

With characteristic vitality and grace, Capote evokes the milieu he has chosen to describe, in sentences that merge lyricism, drama, and sharp observation:

A small red fox is seen at dusk stalking the lonely sea-edged sand-moors. Owls, residing in scrub-pine thickets, warn pheasants of creeping human hunters . . .

In another fragment—the opening paragraphs of an unfinished magazine piece, probably begun in the last year or so of his life—I encountered a different season and setting, and a variation of his narrative voice:

Snowflakes large as leaves lingered in the air. I was happy to rid myself of a cold Park Avenue, exchange it for the warmth of the Waldorf Towers. I was happy anyway. I always was when I was going to spend an evening with Cole Porter.

Here is the author as socialite, awaited by his host in the famous songwriter’s “dazzling” library, where, amid tortoise-shell walls, “the book-shelves, strewn with books and bowls of white lilac, were bars of golden brass.”

As I sat among his stray beguiling sentences, I felt sad about the pages he didn’t write, the works he couldn’t finish, but also more deeply aware of the magnitude of what he had completed—and I believed with great certainty that time would only strengthen the recognition of Capote’s literary accomplishments.

In a sense, I was right. In the decade and a half that followed, most of his published works remained in print and widely available. Then, the years 2004 through 2007 brought a windfall: the release of two major films based on Capote’s life, three significant anthologies (devoted, respectively, to his stories, letters, and essays), several reissues of other books by or about him, and the discovery and publication of a long-lost apprentice novel. Spurred on by the success of the 2005 film Capote, the paperback edition of In Cold Blood returned to the bestseller lists, where it lodged near the top for several months.

But I was wrong about one thing. In my wide-eyed idealism, I had believed that the sensationalistic glow of Capote’s personal life would inevitably fade, along with any other shallow forms of notoriety, to be eclipsed by a growing public awareness of his greatness as an artist. That leap of faith has proven very naïve indeed; still, I retain a certain thin strand of idealism, enough to sustain my belief that he will be remembered for the right reasons: not the oft-repeated litany of addictions to fame, drugs, and alcohol, but the more meaningful addictions to language, memory, mood, and narrative. I like to revisit him where he was at his best: on the page.

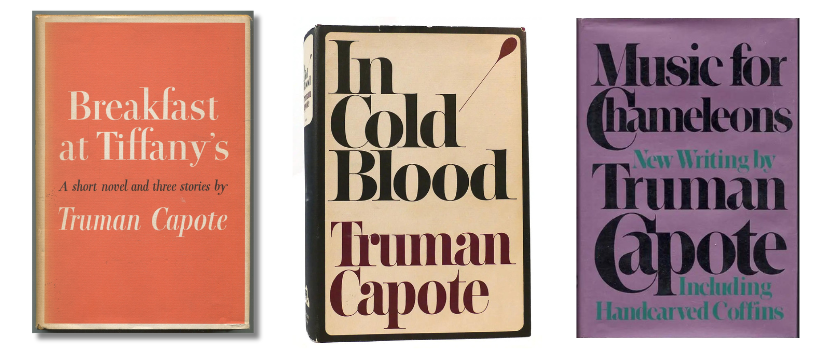

First-edition copies of three works by Capote: Breakfast at Tiffany’s (Random House, 1958), In Cold Blood (Random House, 1966), and Music for Chameleons (Random House, 1980)

An obvious fantasy-double of the author, Holly possesses the nerve to transcend her humble rural origins and the station to which she was born, and embodies the Capote drive to make life livelier and more artful. Beneath this need to change and climb lie desperate motives and intense anxiety. The stakes are high; those who do not somehow invent or exceed themselves are left to sink into mediocrity. More frightening still, life may shape them into psychotic monsters, like the murderers from In Cold Blood.

In this widely hailed “nonfiction novel,” published in 1966, Capote’s lyrical and gossipy impulses are subsumed within a tone of studied objectivity and grim irony. Regarded by many as both the centerpiece and apex of Capote’s career, the book’s deftly orchestrated suspense narrative makes it riveting on first reading—and its unflinching account of human brutality makes it difficult to reread, despite the classical beauty of its composition.

Upon returning to the novel’s prose for a slower, more careful examination after the plot’s page-turning qualities have subsided, one discovers Capote’s well-practiced penchants for lyricism, hyperbole, and satiric description, alongside the stoically delivered ironies and the litanies of sometimes bleak detail. One of the murderers has a face “which seemed composed of mismatching parts. It was as though his head had been halved like an apple, then put together a fraction off center.” In contrast to this creepy portrait, many of the Holcomb townspeople resemble the denizens of a Capote comedy, introduced with characteristic brio: the local mail messenger, known as Mother Truitt, a rather youthful seventy-five-year-old, is a “stocky, weathered widow who wears babushka bandannas and cowboy boots.” The local postmistress, Mrs. Clare, is

a gaunt, trouser-wearing, woolen-shirted, cowboy-booted, ginger-colored, gingery-tempered woman of unrevealed age (“That’s for me to know, and you to guess”) but promptly revealed opinions, most of which are announced in a voice of rooster-crow altitude and penetration.

In audio recordings of Capote reading passages from his writings, the author exhibits hilarious comic timing and a brilliant flair for performance, mixing, without hesitation, comic flourishes into certain passages from In Cold Blood as deftly as with the more overtly comedic Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Listening, one realizes that Capote’s mischievous impulses were not abandoned for his true-crime classic, only redeployed into a smaller supporting role; held in check but used as a counterpoint that serves to heighten, through contrast, the tragic vision that informs the book.

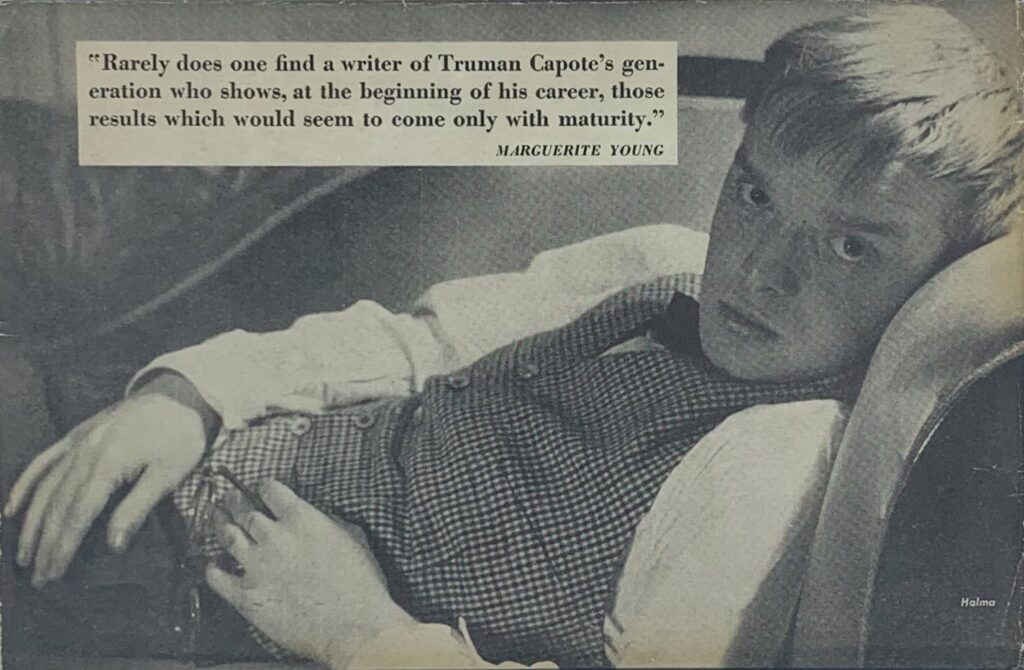

Photograph of Capote on the back cover of his 1948 novel Other Voices, Other Rooms (Public Domain)

It is this nearly absurd insistence on art first—the unfailingly graceful rhythms of his sentences, the precision of his poetic description, the economy of his storytelling—combined with his insistence on never boring his audience—that makes Capote’s best work so potent.

Throughout, Capote’s lyrical turns are not merely ornamental. In the mostly comic “A Day’s Work,” after a particularly comedic scene we encounter this striking sentence: “The rain had returned and the wind increased, a mixture that made the air look like a shattering mirror.” Within the course of the next few paragraphs, Capote stands on Park Avenue alongside his cleaning lady (they are both stoned) and tells her (with “the downpour drenching us”) of his mother’s suicide. He does not explicitly connect the suicide to the foreshadowing image of rain and wind as “shattering mirror,” but the reader feels, consciously or not, the connection, all the more powerful for the restraint with which it has been implied.

Perhaps the book’s most brilliant element is its title piece, “Music for Chameleons.” Here, in a handful of well-polished pages, readers are given what appears at first to be merely an exquisitely described afternoon visit with an elegant aristocrat in Martinique, not so much a story or essay as a bauble, a piece of prose jewelry.

“The most subtle story,” Capote told Edmund White, “is ‘Music for Chameleons.’ Even sophisticated readers don’t understand it. They think it’s about a visit with a woman; they think it’s a travel piece about Martinique. But it’s actually a meditation on murder, about how our passions flog us.”

Capote in 1980 (Jack Mitchell / CC BY-SA 4.0)

The tension Capote sets up between the social graces passing between himself and his hostess, the unexpressed thoughts that he shares only with the reader, the subjects of conversation (ghosts, capital punishment, dangerous-looking masked figures at a street festival, the murder of a gay friend by two sailors he had met in a bar), and the eerie effects of a black mirror into which the author-narrator periodically gazes, turn this unique, understated piece of writing into a brilliant short story. Beneath the glaze of surface beauty it simmers with unsettling implications and poetic ambiguity; it sets the tone, and sets up the themes, of the entire volume, while providing the ideal title. (“Chameleons” can refer to the characters in this story, the characters in all the stories, the readers of the book—or all of the above.) The story’s final image, of a piano played as chameleons scurry across a terrace in Martinique, is perfection: the music of Capote’s prose attracts his chameleon readers with similar elegance. One thinks of Keats: “What shocks the virtuous philosopher delights the chameleon poet.”

It is this nearly absurd insistence on art first—the unfailingly graceful rhythms of his sentences, the precision of his poetic description, the economy of his storytelling—combined with his insistence on never boring his audience—that makes Capote’s best work so potent. His shrewdness can’t fully mask the shortcomings of his intellect—he was not, and never aspired to be, an intellectual heavyweight—but his savvy in narrative construction, twinned with his incisive observations of characters and settings, allow him, like F. Scott Fitzgerald and J. D. Salinger, to build up even the flimsiest material with an exuberance so irresistible that readers glow with the contagious pleasure of the prose. Rather than the synthesis and analysis of complex ideas and the gathering of a wide range of knowledge to reinforce a new perception, he offers the distillation of experience into finely honed expression, marshaling his aesthetic effects to elicit a new sensibility.

Christopher Lehmann-Haupt struck a resonant note in his original New York Times review of Music for Chameleons in 1980, when he observed that Capote had “succeeded in projecting all the facets of his remarkable and varied personality”—including “the side of himself that delights in making up whoppers.” I agree, and I would add that Music for Chameleons reports on the real world in much the way fine fiction does: provisionally, indirectly, subjectively, and, at times, hardly at all. Magicians are only interested in truth insofar as they can toy with it. Capote’s great achievement was the summoning of the incantatory power of language, the deletion of anything that might impede the sensual rhythmic flow of his narratives, and the application of his skills to a widely varied selection of material. Drawn to subjects ranging from the sensational (and sensationalized) to the understated, he used his subject matter as a model with which to display his ability to stylize. Yet the stylizing leads to a vision that illuminates his subjects. Style and content become inseparable.

Two and a half years after his death, on a freezing cold Sunday morning in late January 1987, I attended a lecture, part of a series called “Biographers and Brunch” at the 92nd Street Y Poetry Center in New York City. The speaker, Gerald Clarke, had written but not yet published Capote: A Biography. (When it appeared, in 1988, it became a best seller and will likely remain the definitive work on its subject’s life.) Mr. Clarke discussed the writing of the biography, regaled us with a few charming anecdotes, read from his work, and spoke of the headaches involved in sorting fact from fiction in the many accounts of the garrulous but ever-embellishing author’s life. To illustrate Capote’s tendency to twist the truth into a good tale, Clarke read a late-1950s piece on the meeting of Cocteau and Gide, then explained that after much digging he’d learned that Gide wasn’t in the same country as Capote and Cocteau at the time Capote’s account purports that they met. Clarke, however, was amused, not scornful, in reporting this tendency to lie.

Mr. Clarke took a careful, hesitant approach to the audience’s questions. I particularly recall those of a persistent elderly woman who insisted he should have told us more about Capote’s tragic side. “More tragedy,” she demanded. “Would you tell us now a little about how tortured he was?”

He didn’t, really, and neither have I. With rare lapses, Capote refused to play victim, preferring the more powerful roles of sinner, celebrant, and genius. More importantly, he left a body of work that turns every subject it embraces, however dark or light, into a vehicle for literary art. By doing so, he invented his most lasting self, the one that, as with all great writers, eclipses the mortal self that birthed it and radiates its own self-defined reality. We are left to accept this final, still mercurial, identity: a chameleon poet of shocks and delights.

Portrait of Capote (JSTOR Daily / Wikimedia Commons)

Robert Pranzatelli is the author of a critically acclaimed account of an American dance company, Pilobolus: A Story of Dance and Life, as well as a number of essays published by the Paris Review and other literary journals. He is a longtime staff member of Yale University Press. This essay is excerpted from his eBook A Chameleon Poet: Truman Capote.