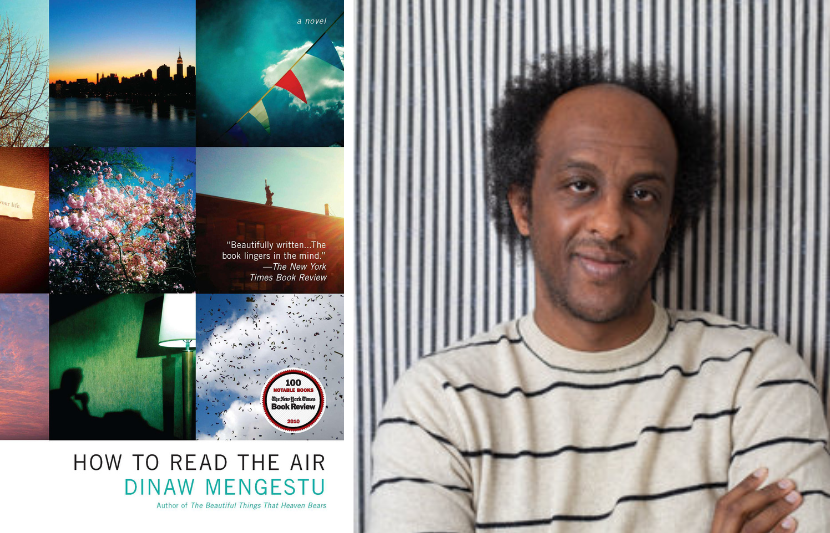

How to Read the Air (Riverhead, 2011) and Dinaw Mengestu (photo: Anne-Emmanuelle Robicquet)

This article was originally published in 2011 on Library of America’s Reader’s Almanac blog.

In our continuing series of guest blog posts by writers of fiction, history, essays, and poetry, Dinaw Mengestu, whose second novel, How to Read the Air, was published last October, describes the impact several American writers have had on his work.

Like many writers, I can’t help but wear my influences on my sleeve, and while those influences are many, and grow each year, I always think first and foremost of Saul Bellow. I read Bellow for the first time in high school, while living in Chicago. An old friend gave me his tattered paperback copy of The Adventures of Augie March and told me this is where I should begin if I wanted to be a writer. He was right in telling me that Augie March was the proper starting point, but he failed to mention how remarkable Bellow’s later novels were.

From Augie March I found my way to Herzog, a novel which even after multiple readings still astounds me with its density, humor, passion and love, and then later to Mr. Sammler’s Planet, Humboldt’s Gift, Henderson the Rain King, and finally to Bellow’s collected short stories. Of all the novels and characters though, it’s the mad, letter-writing Herzog who somehow manages to find his way into all my work, and to whom I return faithfully at least once a year.

Bellow was the first great writer to cement my conviction that there was nothing I wanted to do more in my life than write novels. Since then that conviction has been continually reinforced by other writers who may not share Bellow’s unique style, but in my opinion are equally great. Out of the many writers I would include in that list, the American novelists who come to mind first are:

James Baldwin. While I’ve always admired Baldwin’s novels, particularly Go Tell it on the Mountain and Giovanni’s Room, it’s his essays that have moved and haunted me most. Notes of a Native Son has a restrained, eloquent fury that demonstrates the brilliance of Baldwin’s prose better than anything else.

Marilynne Robinson. Housekeeping, Robinson’s first novel, is unabashedly lyrical. It’s a novel that for me serves as a constant reminder of how great prose can reveal what is sublime in even the most ordinary experiences. Over the years I’ve read the novel at least half a dozen times, and each time I find myself transfixed by the grace of Robinson’s writing.

Edward P. Jones. I read Jones’ first collection of stories (Lost in the City) set in Washington, DC, just as I was finishing my first novel, which was also set in the District. I knew even then that Jones could accomplish in a single story what I had tried to recreate in a novel. I read Jones’s masterful novel The Known World immediately afterward, and then, as soon as it was published, his last collection of stories, All Aunt Hagar’s Children. The three works together create one of the most humane and thorough portraits of African-American life in America.

Born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Dinaw Mengestu grew up in Peoria, Illinois. In 2011 he won the Vilcek Prize for Creative Promise in Literature. He has been honored with a Fellowship in Fiction from the New York Foundation for the Arts, and The New Yorker named him a “20 Under 40” writer to watch. Mengestu’s debut novel, The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears (2007), won the “5 Under 35” award from the National Book Foundation, the Guardian First Book award, the Los Angeles Times first novel award, and was named a New York Times Notable Book. Reviewing it in The New York Times, Rob Nixon wrote: “Saul Bellow shadows these pages: the dangling man, the urban wanderings, the uncle who writes obsessive letters to the authorities. Above all, Mengestu shares Bellow’s genius for the quick, decisive physical portrait. . . . Yet Mengestu uses this talent to open up a wider, more diverse neighborhood of empathies.”

His second novel, How to Read the Air, has already been named a New York Times Notable Book. It prompted the Washington Post’s Ron Charles to write: “By the end, How to Read the Air grows into a tragic and affecting paradox, a demonstration of the limits of fiction, the inability of stories to heal or preserve. And yet there it is, this novel—wholly contrived—offering up its wisdom about the immigrant experience with the kind of power mere facts couldn’t convey.” Mengestu has also written for Rolling Stone on the war in Darfur, and for Harper’s, The Wall Street Journal, and numerous other publications.