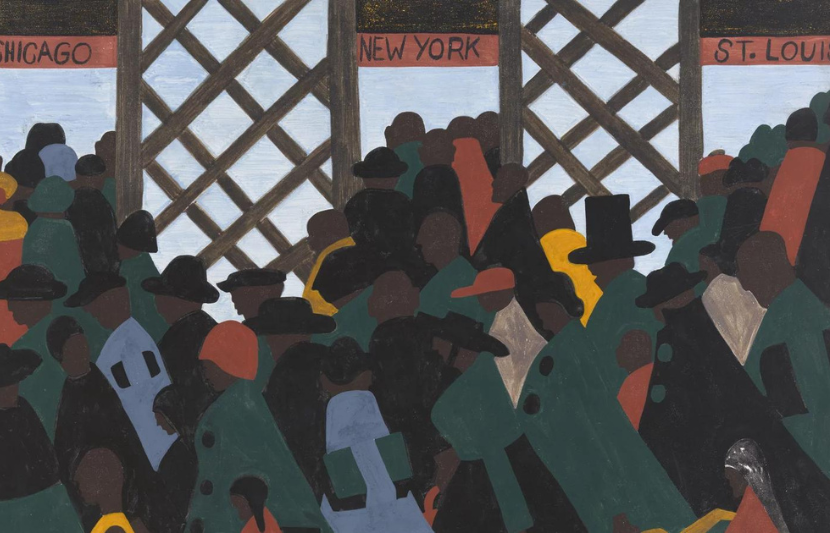

The Migration Series, Panel No. 1, by Jacob Lawrence (The Phillips Collection)

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Reconstruction promised legal equality for all citizens. But after an initial wave of newly enfranchised Black Americans were elected to public office across the south, a novel form of post-slavery repression would emerge: Jim Crow. Named after a minstrel caricature of a Black street singer, Jim Crow was an evolving system of laws and behaviors based on legalized segregation, economic exploitation, racial pseudoscience, and outright violence.

In the first part of Jim Crow: Voices from a Century of Struggle, a new LOA volume collecting writings from the end of Reconstruction in 1876 to the Red Summer of 1919, Professor Tyina L. Steptoe introduces readers to a pivotal yet sometimes overlooked period of American history. (A second volume will cover the period from the Tulsa Massacre of 1921 to the Boston desegregation busing crisis of the 1970s.) Through the firsthand accounts of citizens engaged in the battle over the color line—from outspoken advocates of Black advancement to voices upholding white supremacy—we glimpse an era of contrasts in which Black Americans made unprecedented social, economic, and cultural progress in the face of brutal backlash.

Below, Steptoe discusses the confluence of historical forces that led to Jim Crow, the diversity of Black responses to reinvigorated white supremacy, and the challenges of teaching this frequently harrowing material to students in the twenty-first century.

LOA: Jim Crow is often thought of as a southern phenomenon, but this anthology makes the case that it extended across the country, including the urban north. Can you talk about the national nature of Jim Crow?

Tyina L. Steptoe: When we think about Jim Crow, we frequently say “the Jim Crow South” as a way of framing that time period and defining it spatially. For this book, I wanted to look at the ways that Jim Crow was national.

After the Civil War, African Americans are migrating, in some cases going from rural to urban or, with the Exodusters, leaving the south and moving westward. At the same time, railroads are expanding and making business decisions about who gets to use their services. That’s one of the reasons why railroads are among the first places to have segregation, and where the term “Jim Crow” gets attached.

Freed formerly enslaved people in Richmond, Virginia, 1865 (New York Public Library)

In the south, a lot of this has to do with ideas of hierarchy and who has more status in society. But it also comes up in places like New England, where you still have—even if it’s not written into law—psychological and social understandings of superiority and inferiority that feed into who gets access to the best spaces, the most comfortable spaces.

It’s about business, it’s about hierarchy, and it’s also about the federal government looking the other way when the Supreme Court does rule on it, siding with the segregationists in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the railroad case we think of when we talk about “separate but equal.”

LOA: One of the tragic ironies that emerges in the volume is how the efforts of Black Americans to create institutions for themselves—to take the idea of “separate but equal” at face value—are violently suppressed by white people. There’s also the tension between those like Booker T. Washington, sometimes referred to as an “accommodationist,” and others like W.E.B. Du Bois, who more vocally affirmed the rights of Black people to political and legal equality.

TLS: Many groups and individuals ultimately had the same goal: they wanted to see Black advancement and equality after the Civil War. They just had different approaches for getting there. Region has a lot to do with this as well.

People have called Booker T. Washington an “accommodationist,” but if you ever go to Tuskegee, Alabama, it’s a rural place, far from any city. We have to think about the difference between someone like Du Bois, who spent almost all his life in urban America, and someone like Washington, whose school is in a rural place where there was so much racial violence against any Black person who tried to vote or own something autonomously.

A history class at the Tuskegee Institute, 1902 (Public Domain)

My first book was on Houston, and what I found was that in the 1920s, Black activists were not pushing for integration, but autonomy. The Houston NAACP figured there were enough Black Houstonians and enough of an economic base to support Black entertainment and commercial districts across the city.

If we’re ever going to figure out how to get rid of white supremacy and racism, it can’t just be about making everyone love one another. We have to look at the economic roots.

With the Black town movement that emerges after the Civil War, there’s something similar, where people figure they can have their own communities and not even need to think about white supremacy. If it’s a Black county, you can elect a Black sheriff and have the law enforcement be Black, too. In places where that’s plausible, people push for it. But in places where that’s not as realistic, you see other strategies.

LOA: In your introduction, you discuss how Black southerners moving to the urban north encountered Black populations from the Caribbean, giving rise to many important strains in Black thought during the era.

TLS: Regardless of where they came from, they all shared histories of enslavement. It just happened in different places under different contexts.

In Jamaica, for example, there was a lot of absentee slave-owning, where the enslavers who owned property were not physically there. This created a sense that the island, in terms of its population, was Black. Jamaicans bring that idea of a Black-majority nation with them to the United States. Meanwhile, a lot of Black folks in the United States have a history of being minoritized, even though you have, across the south, huge Black populations. Mississippi and South Carolina had a Black majority for a long time; the eastern part of Texas, Black majority; southern Louisiana. But as a whole, in the United States, the Black population has never been a majority.

At the same time, the United States has an economic base that these immigrant communities didn’t have in Black-majority places like the Caribbean. The question becomes: what if that majority-Black experience and American economic potential were put together, and Black populations began to think in a global way?

It’s an exciting moment around World War I, with growing sense of a worldwide Black population and the ways that people can help one another because they’re all living in some system of white supremacy. It might look different on the surface, but when you dig down, there’s a sense of Black debasement, regardless of whether you’re talking about Jamaica, which was still a British colony, or the colonized nations of Africa. All these people are making contact on the streets of Harlem and saying, “Wait a minute, we’re calling it different things, but this is all the same. What if we started to think about how to fight them all simultaneously?”

The 15th Infantry Regiment, aka the Harlem Hellfighters, in France, 1917 (Public Domain)

LOA: In World War I, you have a large population of Black soldiers serving in the United States Army, some in quite famous units. Did the war represent a transition point for Black Americans?

TLS: It’s significant that this first volume ends in 1919, with the end of World War I representing a break. When I teach courses, World War I is either the beginning or the end of a unit, because it’s such a turning point, globally and for the United States.

For African Americans in particular, there’s so much that happens, even for those who didn’t serve in the military. The war reinvigorates the U.S. economy and recruiters from the Midwest and Northeast start actively recruiting Black men to come take industrial jobs in urban America. There are so many blues songs about going up north written around 1917, 1918. And when people get to the cities, they start building institutions and schools.

People also come out of the war with more money, because in some cases they’re leaving the rural south and sharecropping to take on wage labor. There is a moment of excitement and consumerism in the early 1920s as a result of the expansion of the economy during World War I.

Black soldiers were like Black celebrities during World War I. The NAACP’s newspaper, The Crisis, would talk about soldiers in practically every issue. When they return from Europe and march through the streets of New York, it is such a triumphant moment that it moves Du Bois to pen a short poem. The Harlem Hellfighters are perhaps the most decorated unit of the war. They take Black American music to Paris. They never retreat. Their exploits are in Black newspapers across the country.

This is a moment when there weren’t a lot of Black heroes that many people knew about and could point to. Just looking through mainstream newspapers of the time, even the comic strips managed to have degrading images of Black life and Black people. To have these men who fought in the war, who come back looking bold—that’s a huge moment for people feeling pride in Blackness.

The Harlem Hellfighters parade through New York City, 1918 (Public Domain)

Also—and this is important—they’re armed! There’s a sense of fearlessness that some come home with. You see this in cases like the Houston Rebellion, in 1917, where Black soldiers responded to violent white supremacy in the form of police brutality by taking up arms and marching on the city. In many cases, so-called “race riots” can come to seem like an overly simplified term for talking about the rise in armed self-defense among Black people during this period.

LOA: Alongside the many instances of Black self-assertion in the anthology, we see cases where Black self-defense was treated by white supremacists as grounds for even greater repression. Can you discuss the racist backlash to Black advancement during the era of Jim Crow?

TLS: In a lot of ways, Jim Crow was a cash grab. It guarantees that people have to pay full price for substandard service. Keeping Black folks economically dependent is one of the ways that white supremacy was able to function, and it makes sense when you think about the institution of enslavement. But how do you keep that going after slavery is legally over? Keeping folks economically tied down—through the sharecropping system, or paying Black workers less—is in part how you can subjugate those groups. And there’s a reason why Black businesses were so often targeted with violence.

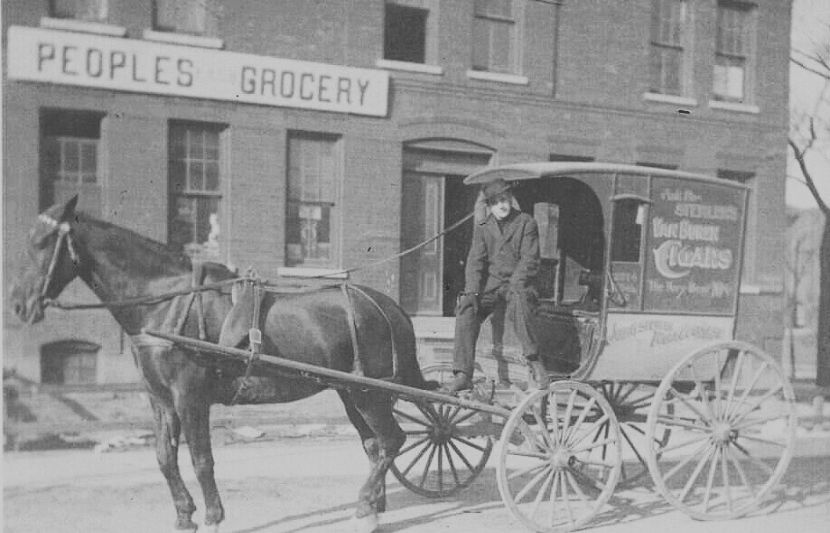

In the case of Ida B. Wells, she became an anti-lynching crusader because her friends had a successful business that competed with a white-owned business, and the Black owners and workers wound up dead at the hands of a lynch mob. We find this pattern again and again where any sign of Black economic achievement directly challenges white supremacy.

This economic tension makes the period of World War I an era of intense violence at home. We see this in East St. Louis, where many Black men had moved from the south. Black workers flooding into the city then becomes attached to white social anxieties: “It sure is a lot of Black men coming up here. Are they’re dating our daughters?”

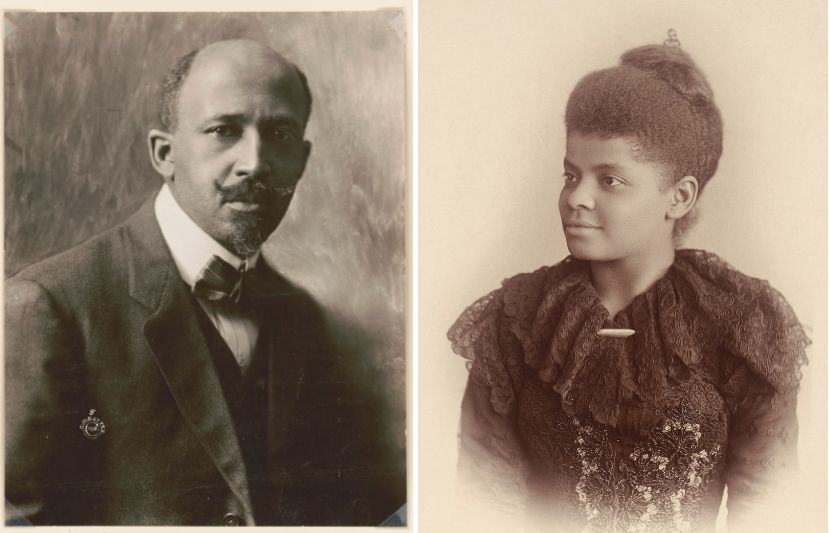

W.E.B. Du Bois and Ida B. Wells (Public Domain)

LOA: You mentioned Ida B. Wells, who is a central figure of the anthology. Can you talk about her and her understanding of Jim Crow along lines of sex and gender?

TLS: Wells ends up being one of the major figures of this era. I have my classes read her pamphlet on lynching and every time I end up with students who are angry—not at me, but because they haven’t heard of her before. U.S. history professors often frame Black leadership in the Jim Crow era as a matter of Du Bois versus Washington, but if we squeeze Wells in there, things start to look different. She captures so much of the arc of this book, beginning with her being one of the women who challenged Jim Crow on the railways.

When we talk about Jim Crow, we can’t just talk about race. Race and gender come together, and Wells is a great example of that. When she’s kicked off a train, it’s because she bought a first-class ticket for what was called “the ladies car” and she refused to move. A lot of railroad companies would not allow Black passengers in the ladies car. Then someone like Wells says, “I’m a lady, I bought a first-class ticket to be in this car,” and she’s kicked out because of her race. Race and gender are converging to shape her experience of segregation. Because of this, she’s one of the people who really saw the ways that segregation was classed, the ways it was racial, and the ways it was gendered.

You see this in her anti-lynching activism as well. She talks about how many lynch mobs accused Black men of raping white women, when her research showed it was often consensual: a Black man and a white woman who’d fallen in love or had a relationship that led to a child. At the same time, what wasn’t being talked about that she highlighted was the rape of Black women by white men—something that began during slavery and colonization. She winds up having to leave the south because she was writing so boldly and naming names.

The People’s Grocery in Memphis, Tennessee, whose Black owners were lynched by a mob in 1892 (Public Domain)

Wells inspired me to include the voices of segregationists and white supremacists in the volume so we could really see what people like her were fighting against. A lot of people, especially today, make racism synonymous with hatred: this person hates people of other races and that’s why they’re creating segregation. But race hatred is too simplistic. We have to look at what these folks were trying to uphold, and part of white supremacy was upholding economic control over the United States. If we’re ever going to figure out how to get rid of white supremacy and racism, it can’t just be about making everyone love one another. We have to look at the economic roots.

Especially with white southerners who had grown up around Black folks, they didn’t think they hated Black people. They thought that everyone had a place and they should stay in it. White supremacists erected statues that glorified the “Mammy” figure with inscriptions like, “They raised us all.” But even as they say they love these women, she’s a servant. It’s a version of Blackness that’s palatable to white supremacy because it’s still economically debased. It takes a lot more than changing people’s hearts to get us out of this system.

Illustration of the Jim Crow character and photo of a sculptor posing with a proposal for a “mammy memorial” (Public Domain)

LOA: The figure of Jim Crow himself is emblematic of this: an object of mockery that’s also held up as an idealized white supremacist version of what Blackness and racial hierarchy should look like.

TLS: The people who went to see minstrel performances thought that Black people were entertaining as long as they’re kept in a derogatory position. There was another minstrel figure named Zip Coon: he was the urban dandy with these sophisticated aspirations who could never quite get it right. So you’re mocking a free Black man who wants to live in Philadelphia, wants to live in New York, and be part of a modern urban society, but he fails at it constantly, and the failure is what makes it funny. White audiences can enjoy that because it fits within the biased idea of Black life.

LOA: Could you speak to the challenges of teaching this material? Is there important context that you feel is helpful for engaging with it?

TLS: One challenge is that anything with “Jim Crow” in the title is probably going to be brutal. I spent so long gathering the documents, and I also teach and write about this material, so there can be a numbing that comes from that. It just becomes part of what you do when you’re at work. I forget what it felt like to learn about this history for the first time, and working on this book made me think about it again.

It’s unfortunate that some people don’t know this happened in our nation’s history. People have a sense that things were bad back then, but they don’t always know how brutal it was, the public nature of the violence. That’s why I try to find figures we can latch on to, who will be our guides. We meet Ida B. Wells, a young schoolteacher biting the hand of a train conductor. That’s a cool story! She seems badass, right? Then later, her friends are killed and she starts writing about lynching. But we know her and her story by the time she starts to describe these horrible things.

As an editor and a writer, I’m always thinking about how to bring people into this world, a world that in some ways sounds like the one we know, and in others is nothing like it.

Child convicts leased for fieldwork, 1903 (Public Domain)

Tyina L. Steptoe is associate professor of history at the University of Arizona and the author of Houston Bound: Culture and Color in a Jim Crow City (2015). Her writing has appeared in Time, American Quarterly, Journal of African American History, and Oxford American, and she is the host of Soul Stories, a weekly radio program on KXCI Tucson that explores “the roots and branches” of rhythm and blues music.