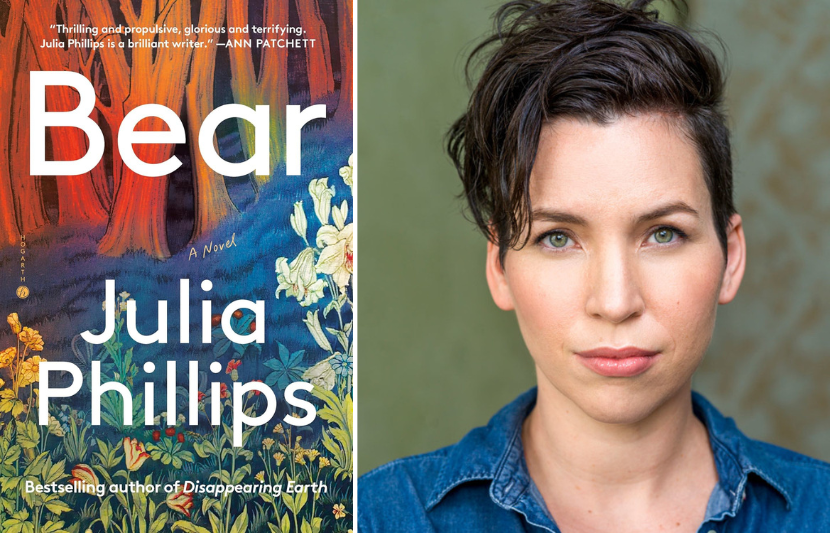

Bear by Julia Phillips (Hogarth 2024)

“Animals do neither good nor evil,” wrote Ursula K. Le Guin in her Earthsea saga. “They do as they must do. We may call what they do harmful or useful, but good and evil belong to us.” Companions and portents, helpers and adversaries, sources of strength and fear, our fellow inhabitants of the planet, despite their wordlessness, remain an indelible part of our social and symbolic fabric.

In novelist Julia Phillips’s Bear, out this week from Hogarth, the sudden interposition of the title creature in the lives of two sisters struggling to make ends meet on an island off the coast of Washington exposes a slippery gradient of diverging desires and buried resentments. What fuels one sibling’s longing to escape her childhood home for good only strengthens the other’s need to stay. The result is scintillating modern mythmaking about the inability of people to fully control their destinies—not to mention the beasts that lurk within us all.

“Julia Phillips’s rare and marvelous new novel weaves fairy-tale magic into a story of sisterhood, daughterhood, care, and devotion,” writes author Jessamine Chan. “Building with quiet fury to its astonishing ending, Bear will capture your heart and mind. I read in a state of wonder.”

Below, Phillips discusses the inherent problems with being a “good reader” and how they led her to imagine a more personal literary canon.

When I was in second grade, my older brother, an impossibly grown-seeming sixth-grader, brought home Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird as his assigned reading from school. When he complained about the task, our father protested. “This is one of the greatest American novels ever,” he told us at the dinner table, while my brother rolled his eyes. “You have to read it. Everybody should.”

As soon as the meal ended, I snuck the book out of my brother’s backpack. It was assigned reading for me, now, too, I decided; I was so smart, I was the one they should discuss books with, they’d see.

For a week straight, I turned the pages, taking in as best I could the story of Scout, her neighbors, and her lawyer father defending Tom Robinson from accusations of something . . . the vicious mob coming for Tom over something . . . the courtroom scenes all centered around something . . . a lot of talk of something not totally legible to me at the time, but generally, I felt, I got the gist. Finally, back at the dinner table, I announced to my family that I’d finished reading To Kill a Mockingbird. “You did?” my dad said. “Huh. What’d you think?”

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee (J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1960)

“I liked it,” I said. Confident, of course, that that was the right opinion. “I just have a question about a word. What’s ‘rape’?”

This was my young reading life, summed up. Aspiring and confused. A “good reader,” which meant, in those days, voracious and eager to impress, I read anything I could get my hands on, mostly with the aim of showing off about it later. I would settle for the text on the backs of cereal boxes and the wrinkled old paperbacks brought home from church book swaps (I gobbled up a ton of Erma Bombeck that way), but what I fought toward were the great books, the right ones, the ones that would pull the attention of the adults in my life.

Prioritizing my own pleasure in reading taught me how to do the same when I wrote.

Which meant, in practice, that I worked at reading all the authors that aligned with those adults’ tastes. Their names paint the picture of the world in which I grew up: John Steinbeck, Ernest Hemingway, Philip Roth, John Updike, John Cheever (“the Chekhov of the suburbs,” he’s called—ideal for this Chekhov-admiring suburban child). At a certain point of my teenagehood, I believe I would even tell people that my reading taste was “the canon.” The canon! The canon, to me, consisted of what grown-ups said I ought to imbibe. Even when I didn’t understand it. Even as I failed to connect.

Cujo by Stephen King (Viking, 1981)

I read these books in the hope that they would shape my own writing into great work that would stand alongside them. Meanwhile, though, I was sneaking different stories in and out of my own bags.

I stayed up late, in my violet-painted childhood bedroom, to read Cujo by Stephen King, which absolutely horrified me. The way King wrote about the body. Its visceral details. The tongue thick in Tad’s mouth. I got every book ever put out by Anne Rice, which was no small feat, and sank deep into the world of Interview with the Vampire. The sex, the drama, the imagination! I couldn’t get enough!

Interview with the Vampire by Anne Rice (Knopf, 1976)

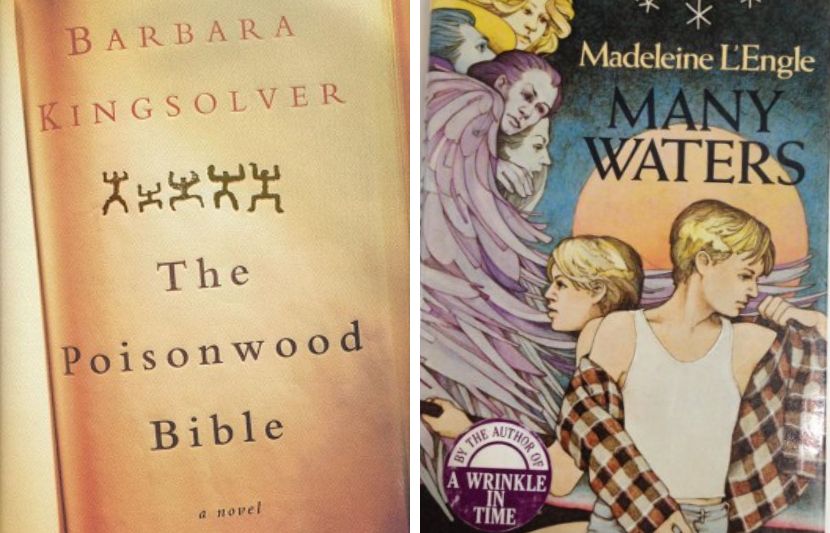

I devoured The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver, which was written by a woman, contemporary, and selling well, so couldn’t possibly, in my paradigm at the time, be a great work of art, but astounded me, wrecked me, with its ambition and depth and beauty. And Many Waters by Madeleine L’Engle, which was for kids, you know, so it couldn’t be serious, and yet it was rich, resonant, and gorgeous, and when I reached its end, I wept.

King’s shocking specificity. Rice’s dark sensuality. Kingsolver’s extraordinary sentence craft and moral clarity, L’Engle’s perception and curiosity. These four writers were some of the first to form my personal canon, the program of great American novels tailored to my taste. As that list of books grew, my own work developed in new, thrilling directions. Prioritizing my own pleasure in reading taught me how to do the same when I wrote.

The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver (Harper, 1998) and Many Waters by Madeleine L’Engle (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1986)

For many years, I’d worked to have the proper influences: literary role models hand-picked by the people I wished to emulate. This was a self-imposed task, and often a baffling one. Eventually it turned out that the stories I most loved didn’t align with the ones I first imagined were impressive to others—the ones I used to announce at the dinner table, the ones that had made a “good reader” of me. My writing has been formed not by the books I believed I ought to read but by books I actually longed to. They spoke directly to me: thrillers, suspense, mysteries, YA, fairy tales, true crime, tell-all celebrity memoirs . . . and Cheever, too, honestly. He’s brilliant. These are the books that still keep me up late reading. The ones that nobody assigned.

Julia Phillips is the best-selling author of the novel Disappearing Earth, which was a finalist for the National Book Award and one of The New York Times Book Review’s 10 Best Books of the Year. A 2024 Guggenheim fellow, she lives with her family in Brooklyn.