Band performing in Texas for Emancipation Day in 1900 (Public Domain)

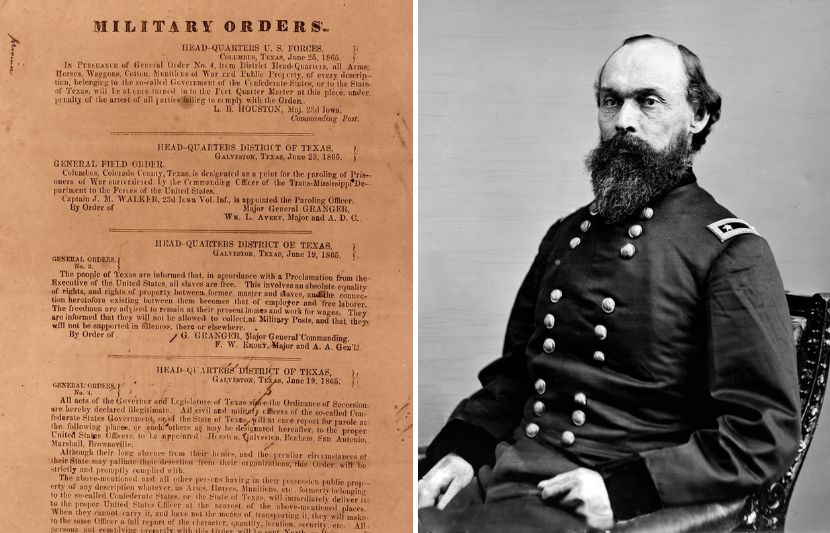

On June 18, 1865, Union Major General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, to take command of the state and the federal soldiers stationed there. The following day, he issued General Order No. 3, enforcing the Emancipation Proclamation and declaring the quarter-million enslaved people remaining in Texas free. While the definitive abolition of slavery in the United States wouldn’t come until the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment in December, Juneteenth represents the end of the institution in the former Confederacy and a culmination of decades of antislavery activism.

From the early days of the antislavery movement, American abolitionists, both white and Black, drew on ideals enshrined in the Declaration of Independence to criticize the slave trade and involuntary servitude. Anthony Benzenet, a tireless campaigner for abolition, points out the hypocrisy of slavery in an essay included in LOA’s American Antislavery Writings:

It becomes a matter of utmost weight to the Americans. . . to consider how far they can justify a conduct so abhorrent from these sacred truths as that of dragging these oppressed strangers from their native land. . . . How inconsistent is this abhorrent practice with every idea of Liberty, every principle of humanity.

General Order No. 3, declaring all enslaved people in Texas free, and Major General Gordon Granger (Public Domain)

Other writers led a theological crusade against slavery, using Christian ethics to attack the institution. Lemuel Haynes, the first ordained Black American minister, writes in Liberty Further Extended, featured in LOA’s recently published Black Writers of the Founding Era volume:

It hath pleased God to make of one Blood all nations of men, for to dwell upon the face of the Earth. Acts 17, 26. . . those privileges that are granted to us By the Divine Being, no one has the Least right to take them from us without our consent.

Criticism of slavery was not limited to reasoned arguments. In the earliest known American satire against slavery, also featured in American Antislavery Writings, John Trumbull mocked contemporary defenses of human bondage:

Is not the enslaving of these people the most charitable act in the world?. . . . We endure the greatest fatigues of body, and much unavoidable trouble of conscience, in carrying on this pious design; we deprive them of their liberty, we force them from their friends, their country, and everything dear to them in the world. . . so much are we filled with disinterested benevolence!

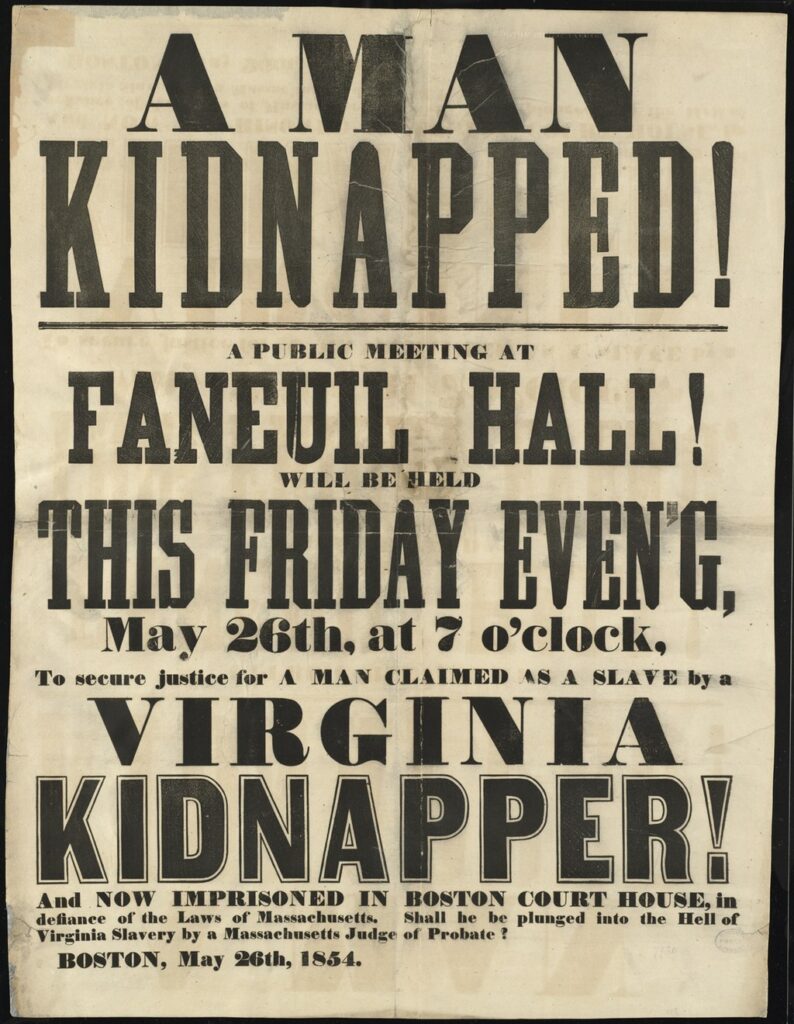

Broadside publicizing the arrest of the fugitive slave Anthony Burns (Boston Public Library / CC BY 2.0)

As the continued existence of slavery further polarized American society, ultimately leading to the Civil War, antislavery writers advanced the cause by ramping up moral pressure. After the conviction of fugitive slave Anthony Burns in Boston, Henry David Thoreau called on Americans to take up the cause of abolition in an 1854 speech:

The law will never make men free; it is men who have got to make the law free. They are the lovers of law and order who observe the law when the government breaks it.

As the war raged on, abolitionists became increasingly unsatisfied with Lincoln’s perceived acceptance of slavery. In “The Prayer of Twenty Millions,” Horace Greeley, the famed newspaper editor and publisher, urged the president to embrace emancipation and turn the Civil War into a fight for abolition:

On the face of this wide earth, Mr. President, there is not one disinterested, determined, intelligent champion of the Union cause who does not feel that all attempts to put down the Rebellion and at the same time uphold its inciting cause are preposterous and futile. . . and that every hour of deference to Slavery is an hour of added and deepened peril to the Union.

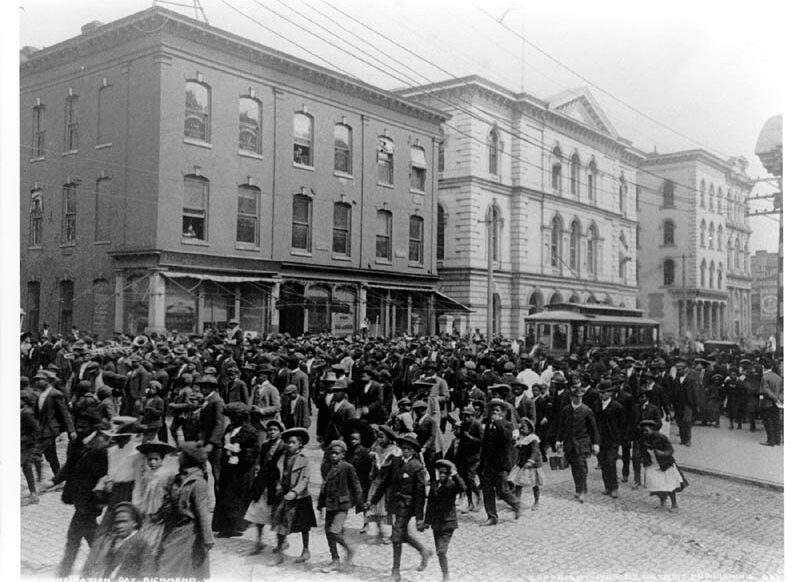

Emancipation Day, Richmond Virginia, 1905 (Public Domain)

On Juneteenth, we not only commemorate the broken chains of bondage of millions of Black Americans, but also remember the contributions of the righteous activists, writers, and politicians who bent the moral arc of the United States toward justice.