Robert Frost in 1943 (Eric Schaal / The LIFE Picture Collection / Getty Images)

More so than with almost any other American poet, Robert Frost’s lines have a way of getting stuck in your head. Whether encountered in a school assignment or a dramatic reading in a movie, his voice strikes your ear with the familiar sound of vernacular speech, then burrows deeper, becoming stranger and more complex the more you mull it. Months or years later, his words might bubble up in your mind unbidden, somehow richer and more meaningful than you remember.

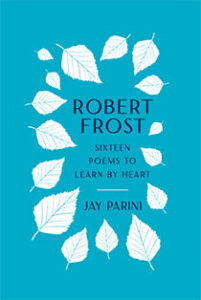

As Jay Parini, Frost biographer and author of the recently published Robert Frost: Sixteen Poems to Learn by Heart, noted in a recent LOA LIVE event, “Frost gives us a language that’s appropriate to our experience again and again.” Not just the grandfatherly figure of a bygone pastoral New England that he cultivated in his public persona, Frost was also a writer of immense but understated wisdom and intricacy, equally capable of rendering sublime scenes of nature and humbler portraits of human grief in his poems. Even his shortest works are worlds within worlds, spinning out fresh revelations with each re-reading and encouraging us to make them a permanent part of our inner lives.

Below, Parini talks about the benefits of memorizing verse, why one critic famously called Frost “a terrifying poet,” and where to turn next once you’ve committed your first sixteen poems to heart.

LOA: Many readers encounter Frost for the first time as students through works such as “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” and “The Road Less Traveled.” What makes his poetry worth returning to?

Jay Parini: Frost always thrills attentive readers with his gorgeous phrasing and perfect timing in the poems. I find myself dazzled and surprised by even the old chestnuts again and again. There are depths that keep yielding new insights. I never get to the bottom of a Frost poem. He claimed to have an “ulteriority complex,” and that is what makes the work so strangely open to new readings.

LOA: You’ve taught Frost for many years. What has that been like?

JP: I’ve taught Frost to thousands of students over fifty years of college teaching. They’re almost always hooked, impressed by his memorable language, his deeply human way of engaging a reader. “Home Burial,” for instance, always shocks students. But especially “Out, Out—” never fails to elicit a gasp from first-time readers. That ending shakes them to the core: “No more to build on there. / And they, who were not the ones dead / Turned to their affairs.”

Watch: How to Memorize a Robert Frost Poem

LOA: In your introduction, you speak about the value of memorizing a poem. “A good poem is a prayer,” you say, “and—like prayer itself—it brings us into conversation with eternity.”

JP: Memorization is what brings me to the language of the poems in the middle of the night, on a long drive, on a run through the woods. You don’t want the interference of a cell phone. You want to possess the words, to own them. Only memorizing a poem will offer that.

Think about actors. They get used to memorizing vast passages. It’s not hard. You just read it aloud again and again, then—like an actor in rehearsal—you go “off-book,” recite. You fail, then try again. It only takes a few times and you have it.

Robert Frost in 1941 (Library of Congress)

LOA: Frost did not achieve public recognition until he was almost forty, and yet today he is among the most well-known and widely read poets in English. How would you summarize Frost’s literary trajectory?

JP: Frost isn’t a poet who has much of an arc. From start to last, he’s Frost. Maybe during the Great Depression you get a few poems keyed to the era: “Two Tramps,” “Provide, Provide,” “New Hampshire.” For the most part, there isn’t a lot of development, although a late poem, “Directive,” is a kind of summary work, one that brings all his gifts to bear in one long poem of extraordinary depth.

Memorization is what brings me to the language of the poems in the middle of the night, on a long drive, on a run through the woods.

I don’t like much of the very late work: it’s often jokey and not like the great poems. But he started with such a bang, with North of Boston. Hard to beat that.

Frost is one of the three great modern American poets: Eliot, Stevens, and Frost. Frost is the most American of them all, focused on the speech and people of New England. I think you’d find that Frost’s voice has quietly rippled through poets of great strength, such as Richard Wilbur or Seamus Heaney. Heaney was a close friend of mine, and he told me that Frost was probably his main influence.

Watch: Jay Parini and Tracy K. Smith Discuss Frost on LOA LIVE

LOA: Speaking at Frost’s eighty-fifth birthday celebration, the critic Lionel Trilling said (to Frost’s surprise and displeasure), “I regard Robert Frost as a terrifying poet.” It’s an often-quoted observation. What did Trilling mean by that, and why did Frost take offense?

JP: I think Frost was afraid of his dark side. He waited a long time for the acclaim that came in abundance in his later years. He was a wisecracking, avuncular figure on the platform, and he gave endless readings to large crowds. They didn’t want to be frightened by poetry. As a result, he never read aloud certain amazing poems, such as “The Subverted Flower.” He tended to read more cozy poems, such as “Mending Wall” and “The Road Not Taken” or “Birches.”

But it’s hard to go very far into Frost without seeing the dark side, as in “Acquainted with the Night,” “Provide, Provide,” or “Design,” which contains the line: “What but design of darkness to appall?” His best work is chilling. There’s not much comfort in Frost, although nature does speak to him, and to us, through him. And there is some assurance there.

LOA: It must have been difficult whittling down Frost’s oeuvre to sixteen poems to present in this book. What narrowly missed the cut?

JP: Frost left behind fifty or so great poems. I hated to lose “Provide, Provide,” “The Subverted Flower,” “The Most of It,” “The Silken Tent,” and so forth. All great poems. But I went with the most obvious and most popular of his poems. The essential poems.

Readers looking for more should simply see Library of America’s collected Frost edition and live in the pages, even the letters and essays. Frost was a splendid writer of essays. “The Figure a Poem Makes” needs to be read.

Jay Parini, the D. E. Axinn Professor of English and Creative Writing at Middlebury College, is a poet, novelist, biographer, and critic. He is the author of Robert Frost: A Life, Why Poetry Matters, and Borges and Me: An Encounter, among many other works of nonfiction. His books of poetry include New and Collected Poems, 1975–2015 and The Art of Subtraction.