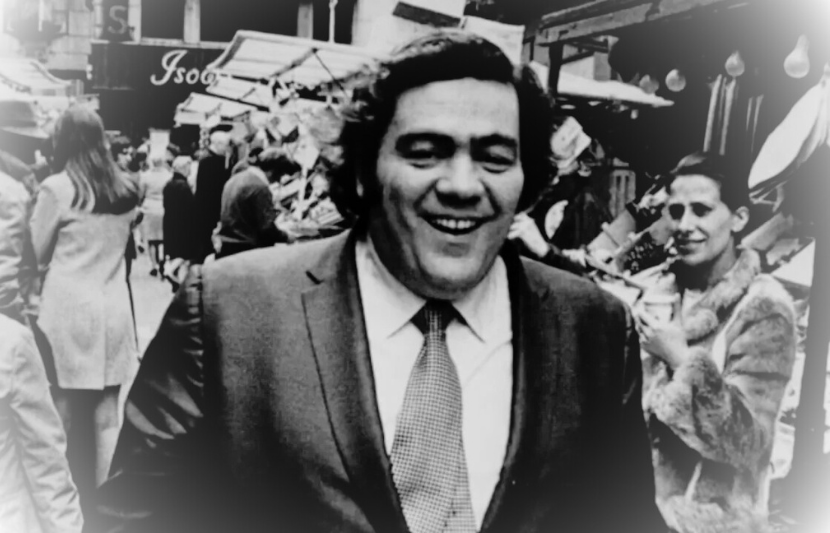

Still of Jimmy Breslin from the 2019 documentary Breslin and Hamill: Deadline Artists (HBO)

On the night John Lennon was killed, Jimmy Breslin rocketed out of bed in Forest Hills, Queens, at 11:20 p.m., journeyed into Manhattan to report the story, and made a 1:30 a.m. deadline for that day’s issue of the New York Daily News. “I don’t think there is anybody else who can do this kind of work this quickly,” he commented, with characteristic humility, in a headnote when the column was reprinted in 1984’s The World According to Breslin.

But if reportorial speed was a point of pride for the Pulitzer-winning journalist, it was the astounding power, panache, and precision of his writing that cemented his reputation as one of America’s most influential and revered newsmen. An old-school shoe-leather investigator who climbed tenement stairs and hounded public officials in search of the stories he knew existed in every nook and cranny of New York City, Breslin was also a consummate artist, a reader of Dostoevsky, and a moral force who championed the underdog while shredding the glitzy facades of the monied and corrupt.

In the recently published Jimmy Breslin: Essential Writings, acclaimed New York Times columnist Dan Barry selects seventy-three of the legendary writer’s pieces and two book-length works to create, as the Wall Street Journal calls it, “a pocket history of our times” spanning the assassination of JFK, the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, the AIDS crisis, and the ascent of Donald Trump.

Below, Barry discusses Breslin’s profound impact, the bygone world of NYC print journalism he came up in, and how he never failed to find the hidden human element in history as it unfolded.

LOA: At last month’s LOA Live event, you told a fantastic story about the first time you met Jimmy Breslin. What was your relationship with him like?

Dan Barry: It was pretty friendly. He would check in on me every now and then, and I’d check in on him. I was a nominated finalist for the Pulitzer twice, which is a glorified way of saying I didn’t win, and the second time, he called me up and left this long message. He told me that awards mean nothing, that’s not why we’re in this business, just tell the story, you’re great, keep doing what you’re doing. It was a weird but deeply comforting pep talk by one of my journalistic heroes after having not won a Pulitzer.

In the final years, he was following the same routine of getting up and swimming and then writing. That’s just an indication of how his mind worked and how he navigated the world as a storyteller. He processed what was happening to him and what was happening in world affairs through story, trying to figure out how to put it in words, and he did that up until the day he died.

Watch: Dan Barry, Mike Barnicle, and Mike Lupica on the time they met Jimmy Breslin

LOA: The LOA volume gives you a sense of Breslin’s almost unbelievable level of output and dedication to the craft of journalism. What set his approach apart from other reporters?

DB: One of the things that distinguished Breslin was that he insisted on witnessing the story himself, going to the tenement building where there had been a police shooting or to the scene of a riot. He would witness the squalid conditions of someone living in public housing because the housing authority wasn’t providing services properly, and he would write about it with both grace and rage. He would go to these events and back to the newsroom and then write the column in almost short story form.

After that, he would go home and get into bed because he was so overwhelmed by what he had witnessed, what he had felt. I think that one of the reasons his work stands out is that the empathy comes off the page. He understood loss, he understood abandonment. His father had skipped out on the family when he was four or five. He understood suffering and was able to convey that through his writing. And then he would basically have to call a timeout.

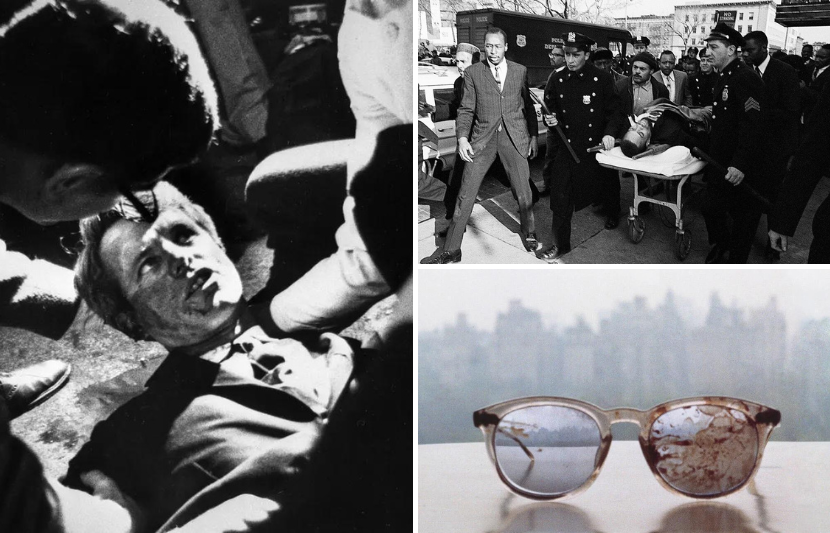

After RFK’s assassination, he went through a bout of depression. I think that really rocked his world. He would struggle with processing the human condition that he witnessed.

Robert F. Kennedy after being shot in Los Angeles in 1968 (Boris Yaro / Los Angeles Times), Malcolm X on a stretcher following his assassination in New York in 1965 (Public Domain), and John Lennon’s blood-smattered glasses (Yoko Ono)

LOA: There’s a great headnote at the top of the article about John Lennon’s assassination where he talks about the speed at which he pulls stories together in these moments of crisis. I’m also thinking of the article about Donald Trump, which is on the one hand a criticism of Trump, but also a criticism of journalists who sit in their cubicles and don’t do the work of hitting the streets and going into the tenements and coming face to face with their subjects.

DB: What he was saying back then—and I think it winds up being rather prophetic—is that Trump was a creation of the media. The guy, to Breslin’s lights, was an empty suit and a bit of a con artist. Breslin was saying that all these reporters were being bought because The Donald called them up and flattered them, and Breslin was having none of it.

Also, to your point, implied in that column is that these journalists are in the newsroom rather than out on the field, waiting for a call from The Donald about Marla Maples or some other nonsense and thinking that’s news. Breslin was absolutely scathing on that score, not only in his assessment of Trump, but also in his assessment of others in newsrooms, including the newsroom of The New York Times.

1931 photo of a signpost at the corner of Queens Boulevard and Grand Avenue pointing the way to Ridgewood, Brooklyn, Maspeth, Corona, and Jamaica, where Breslin was born in 1928 (NYC Municipal Archives)

LOA: Breslin came up in New York City journalism and had remarkable access to sources from all walks of life. How did being so embedded in the city’s culture and society inform or propel his career?

DB: He was authentically New York. But also, because he came from Queens, he had the clear-eyed vision of the outsider, the ability to look at the human circus of Manhattan and all its power elites and public officials and celebrities and assess it clearly and properly and with wit. He refused to accept any nonsense. He had a great bullshit detector.

By the same score, he was a creation of his own making. There was Jimmy Breslin, and then there was the person behind Jimmy Breslin. It was Jimmy Breslin, the character, the sloppily dressed guy who drank a lot and hung around saloons with barflies and half-assed wise guys. He was a guy who might take a swing at you. There was that persona, but there were also other kinds of Jimmy Breslins, too.

At some point he said there were so many different versions of himself that he couldn’t always know who he was. I think the truth was that the Jimmy Breslin persona that was featured in, say, Piels commercials and late-night talk shows was distinctly different. It served him well to have this kind of persona.

He was a quote, unquote, “character.” But the truth of the matter was that he stopped drinking for the last forty years of his life. He swam every day. He read voraciously and knew the classics. That’s different than the persona of the guy at the end of the bar at Pep McGuire’s off Queens Boulevard.

The reason he became so well known is because there was no one writing like Jimmy Breslin in the early ’60s and through the ’70s. He had an entirely different style, a distinct style, and he was a champion of the people. He was the guy sticking up for people living in tenements and people working day jobs at an hourly wage. He was the guy who recognized the heroism in their everyday lives.

That built up over the years to where Breslin became so famous that there’s a line about him in When Harry Met Sally. If the reference had been to, say, Mike Royko, you’d be taking a chance. But at that time, everyone knew who Jimmy Breslin was.

LOA: Breslin came from an Irish American background and wrote a lot about race and ethnicity as political and social vectors in New York City, perhaps most notably in The Short Sweet Dream of Eduardo Gutiérrez, the nonfiction manuscript where he tells the story of a Mexican immigrant who dies at a construction site in Brooklyn. Did he see parallels between his own upbringing and the experiences of newer groups of immigrants in the city?

DB: In the Irish America that he grew up in during the 1930s and ’40s, there were still memories of discrimination, of bigotry and targeting the Irish. People whose grandmother had fled Ireland because of the famine. People directly affected by the Irish Rebellion and fight for independence, which began in 1916. This was all part of the Irish American zeitgeist during Breslin’s childhood. Then in the 1940s and ’50s and ’60s in New York City, oftentimes Irish Americans were doing the civil service jobs: they’re the cops, they’re the firefighters, they’re the guys working for the transit authority. I think it’s natural for a guy growing up in that kind of environment to focus on the next wave of immigrants, the next wave of the underprivileged or the ignored or the exploited.

And Breslin was so harsh on the Irish America of later, the Ronald Reagan Irish America, where Irish Americans were leaving the Democratic Party and going to the Republican Party. He thought that they were betraying their roots. They were forgetting where they came from, which he believed was a cardinal sin. He would use these phrases—I use one of them in the obituary I wrote of him for The New York Times—about the Irish with “shopping-center faces” who are so materialistic and wrapped up in new values that they’ve forgotten where they came from. For him, there would have been nothing worse than an Irish American racist. Like, are you kidding me? Do you know anything about your heritage?

President Ronald Reagan attending a St. Patrick’s Day luncheon hosted by speaker of the House Tip O’Neill in 1983 (Public Domain)

LOA: Breslin’s sportswriting intersects with his work on politics and culture in so many fascinating ways. Could you talk about Breslin as a sportswriter and how that phase of his career led to the columns and journalism?

DB: Beginning in the late 1940s, and through the 1950s, he was working at a variety of New York City newspapers and Long Island and Queens newspapers, almost all of which are no longer in existence. He was a sportswriter and a sports editor then. He was very well versed in boxing, in baseball, in horse racing.

When Tom Wolfe and others were talking about New Journalism and they would include Breslin, he was both flattered—I’m sure he would have been annoyed if he had been left out—but he also called bullshit. He was saying, you can call it New Journalism, but what we’re doing is pretty much what sportswriters have been doing forever.

He talked a lot about the sportswriter sensibility of seeing a game as an unfolding human drama. One example would be when Bobby Thomson hit the Shot Heard ‘Round the World in 1951 to send the New York Giants to the World Series. Thomson is rightly surrounded by a bunch of sportswriters, but the smart sportswriter would go to the loser’s locker room and there would be the pitcher, Ralph Branca, who now for the rest of his life will be known as the guy who gave up the home run to Bobby Thomson.

So where is the story? Is the story seeing Bobby Thomson receiving adulation or is it more identifiable to be with a guy who threw one pitch and is forever remembered for failure? That sensibility is what Breslin applied every day. He would talk about sportswriting as definitive for the kind of reporting he would do.

You can see that famously when he went to John F. Kennedy’s funeral and he’s standing where all the dignitaries were gathering. He saw Haile Selassie dressed in some kind of military uniform, and he saw three thousand reporters and cameras, and he said, “There’s no story here for me.” Actually, what he told a classroom in a recording I heard recently was, “For me, that is death.” He did a gut check with [Washington Post columnist] Art Buchwald and said he was thinking of going to Arlington National Cemetery and seeing who was digging Kennedy’s grave, and Buchwald said that sounded like a good idea.

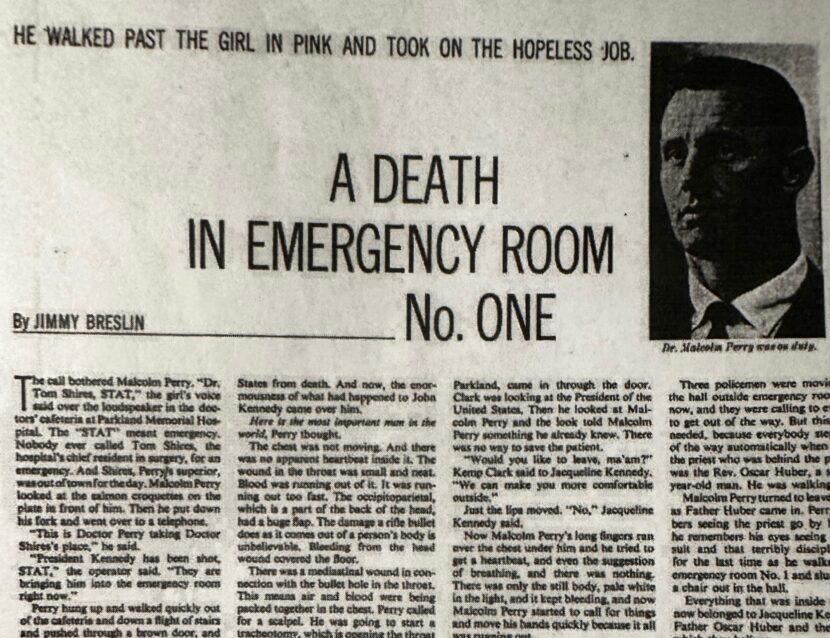

“A Death in Emergency Room No. One” by Jimmy Breslin (The Saturday Evening Post, December 14, 1963)

What he is basically doing—it’s a little bit of a mixed metaphor—was going to the loser’s locker room. He was going away from the crowd. The crowd is death.

That’s where the sportswriting background and sensibility followed through all his life. Who is talking to AIDS patients in 1985 and really listening to them? Well, it’s this guy who’s known for being brash and boisterous and getting into it with the Son of Sam and doing beer commercials: Jimmy Breslin. He’s the one sitting at the bedside of David Camacho, who’s succumbing to AIDS, and he’s listening to the stories and putting humanity to something that everyone else was averting their eyes from.

LOA: Could you point readers to a few less-known columns or works by Breslin that you think deserve attention?

DB: There are many. If you want to see his breadth of knowledge about sports, there’s a book review of The Baseball Encyclopedia that’s wonderful. Then I’d recommend the Donald Trump piece because of how prescient it is. But there are two others I’d mention.

In the early 1960s, there were Mafia wars going on in New York, and there were these brothers known as the Gallos. They came from what is now called Carroll Gardens and they were, to use the technical term, nuts. Joey Gallo used to keep a lion on a leash in Brooklyn. Just imagine that!

Mugshot of Joey Gallo from 1961 (Public Domain)

Everyone knew who the Gallos were; they were always jammed up and getting into shootouts. One of the pieces in the volume has Breslin going up to Gallo’s grandmother’s house. It was basically the Gallo homestead, an apartment on the third or fourth floor of someplace in South Brooklyn. He sits with their grandmother and she talks to him, saying outrageous things, and you get the sense that her grandchildren’s comfort with violence comes from her.

You come away amazed that Breslin had the audacity to knock on this woman’s door, managed to do this on deadline, and he describes it beautifully and with great humor. And you still feel like this woman has her dignity intact.

He was the guy sticking up for people living in tenements and people working day jobs at an hourly wage. He was the guy who recognized the heroism in their everyday lives.

I mentioned the famous piece about the man who dug JFK’s grave, but I’d also call attention to the story Breslin did right before that, where he spent time with Malcolm Perry, the emergency room doctor presented with the case of the President of the United States being wheeled in. I think he was eating a sandwich and then he’s called to the next case and it’s John F. Kennedy right in front of him. Breslin’s description of that is unbelievable.

Kennedy gets shot, Breslin goes down to Dallas, he does the story about Malcolm Perry, then he does the gravedigger column, and then he eventually returns to New York.

And what does he do? He comes back from writing one of the most famous newspaper columns, if not the most famous newspaper column of all time, and on Thanksgiving, just a few days after Kennedy’s assassination, he goes to an automat on 8th Avenue and 34th Street. He describes these lonely men sitting there drinking cups of coffee and putting their cigarettes out in ashtrays and crumpling their napkins as they’re trying to kill time. And he ends that column by saying, in essence, this is right, this is how it should be today: people sitting there quiet, with a waiter in white coming to pick up the crumpled napkins.

To me, that’s about the nation in shock, the nation in mourning. Breslin is describing a nation in grief through the automat without ever mentioning the assassination, without ever mentioning the surname Kennedy. He’s just describing a gray, somber day in the wake of this cataclysmic event. To me, it’s like poetry.

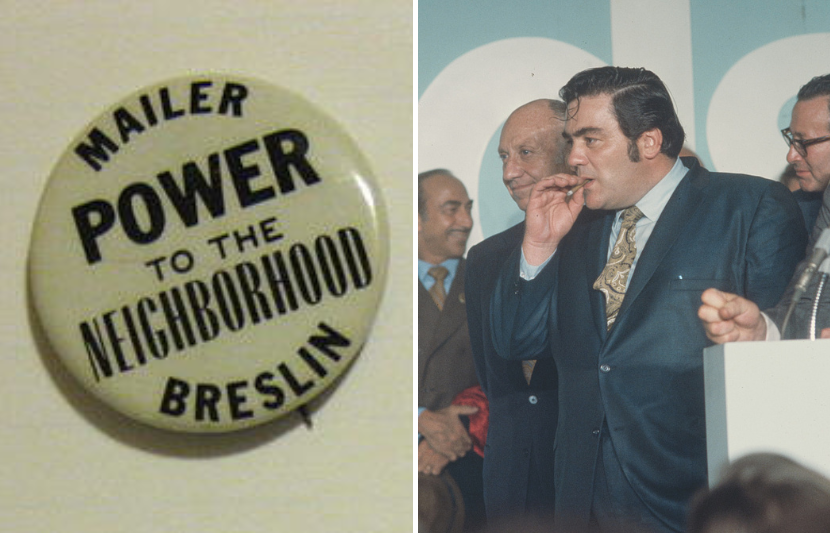

Campaign button for the Norman Mailer–Jimmy Breslin 51st State ticket in 1969 (CC BY 3.0) and Breslin at an event for New York City mayor John Lindsay circa 1970 (Bernard Gotfryd / Library of Congress)

Dan Barry is a reporter and columnist for The New York Times. His awards include the Best American Newspaper Narrative Award in 2015; the Meyer “Mike” Berger Award from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism in 2005; and the American Society of Newspaper Editors Award for deadline reporting in 2003. He is the author of several books, including This Land: America, Lost and Found (2018), a collection of his “This Land” columns first published in the Times.