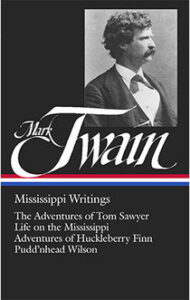

Cover of James (Doubleday, 2024) and portrait of Percival Everett (Michael Avedon)

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn isn’t just Mark Twain’s masterpiece. This picaresque novel set up and down the banks of the Mississippi in the era of the antebellum South has become so central to our national mythology that it sometimes seems more like a projection of the collective American psyche than the literary work of one author. Endlessly reexamined and reinterpreted, Huck Finn is remarkable not only for what it relates—a young boy’s flight from familial abuse and stultifying domesticity, the friendship of necessity between him and the runaway slave Jim—but for the wider, more complicated world of racism, violence, and human darkness it intimates.

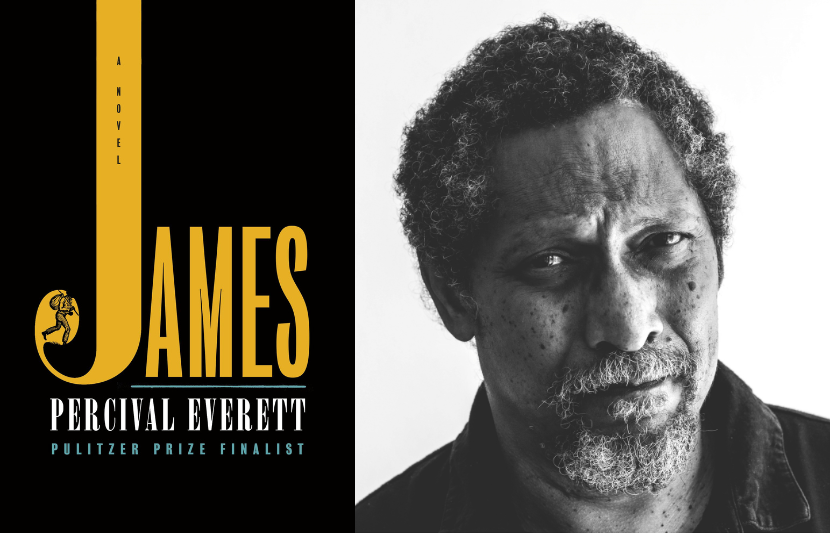

In James (Doubleday, 2024), acclaimed novelist Percival Everett takes readers into regions of Huck Finn that Twain, for all his skill, could neither see nor navigate. Told from the analytical, deep-feeling, and justifiably enraged perspective of Jim, the novel is less a retelling of Twain’s Adventures than an act of liberation for its protagonist. Writing in his own words, adamant in his full humanity, and bearing witness to the nightmare of slavery, Jim seizes a double freedom: first an escape from physical bondage, then the emancipation of his language from the caricatured vernacular of the original. The result is revelatory, unflinching, and hilarious, breathing new life into Twain’s classic even as it lays bare its most damning blindnesses.

Below, Everett speaks with LOA’s online content manager Ben Lasman about his abiding love of Twain, the idea of “adventure,” and how humor and irony function as tools of survival.

Illustration of Jim and Huck from 1884 edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (E. W. Kemble / Public Domain)

LOA: Who is Jim in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, who is James in your novel, and what is the link between them? How do you connect these characters who share so much but also have quite different experiences across the two books?

Percival Everett: First of all, I have to say that my decision to write this novel is in no way a reflection of any kind of dissatisfaction or deficiency I find with Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. That’s a great work, though I don’t think reading it is necessary for understanding James, partly because the whole business of Huckleberry Finn is so embedded in our culture that we sort of know what it is without even knowing it. That I get to participate in this discourse with Twain, that’s the exciting part for me.

The Jim in Twain’s novel is an important character, and a symbolic character representing slavery, though Twain cautions us not to find any deeper meaning than an adventure story in it. I think that is being coy. Twain would not have been and was not capable of rendering Jim’s story. It was far removed from his experience, though he could have stood witness and did stand witness to many people like Jim. The Huck character suffers familial oppression, which in its way is no different from any other kind of oppression, but it’s still not the same thing as slavery. Huck doesn’t have to worry that when he runs, he will be murdered.

When I started thinking about the novel, about the fact that Jim’s lack of agency was not a failure but an impossibility, I decided that I needed to give this character some agency.

LOA: Can you recall any early encounters with Twain’s original? How did you approach writing within that pre-existing textual world?

PE: I think my first experience with it was in an abridged version, a kids’ version. I don’t remember when I was introduced to an unabridged Huck Finn. I loved Twain before I read Huck Finn, because I loved Roughing It and Life on the Mississippi. That’s where I encountered his sense of humor and who I recognize as Twain.

Mark Twain in 1907 (A.F. Bradley / Public Domain)

I wouldn’t say that my reading of Huck Finn was so profound. What’s profound is the fact that Jim exists in this novel as an emblem of something that is necessary to the American psyche, which is dealing with this life in American history of slavery, and that we really in this country cannot escape it. Every story echoes that tragedy.

When I decided to write James, I read Huckleberry Finn some fourteen to fifteen times in a row. And I mean nonstop: I would finish the last page and go back to the beginning. I needed to do that so I wouldn’t be rehashing the story. I did it and then I never looked back at the text. I did it until it was all nonsense, until none of it fit together, much in the way that when you repeat a word over and over again, it starts to sound strange.

That allowed me to own the material, and also to come to terms with a failing of Huckleberry Finn, which is that the novel is uneven. Twain stopped midway through and paused for several years and then came back to it with a different mission. He returned to it in a mercenary way; he wanted to sell this thing and make some money. That explains to me the reintroduction of Tom Sawyer toward the end and weighing so heavily on the adventure part of the story. That’s also the part where Jim becomes more of a pawn. The relationship between Jim and Huck falls away at the expense of the adventure. But again, that’s just something that is there, and not a mark on the impression that the novel makes on the culture or on me.

At the base of everything I write is an interest in the construction of language and how language actually works: how it is that these marks and sounds that we make convey meaning to someone else.

LOA: Huckleberry Finn opens with a note claiming that the book is full of accurate representations of regional dialect. And then James starts with an explanation of the hidden world of language, in which vernacular speech operates very differently for Black and white characters for reasons of safety, secrecy, and signification.

PE: The use of the vernacular is obviously really important in Huck Finn, culturally. The fact of the matter is—and I think we lose sight of it when we talk about things like “standard” English—all language is dynamic and fluid and constantly changing.

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, first edition (Charles L. Webster and Company, 1884)

In any conflict or war, the first casualty is always language, in that someone takes over. At risk of being too political here, you see it in the situation in Palestine, where there’s been a conflating of anti-Semitism with anti–Israeli government, and that’s an unfortunate trend in language. Like all attempts to control language, it blunts dialogue and is meant to put someone at a disadvantage.

That’s what happens with the expectations slave owners had of how slaves were going to speak. To expect that kind of thing is not only infantilizing, but it also reinforces preexisting conditions: one is for comfort and one is for control.

All that aside, at the base of everything I write is an interest in the construction of language and how language actually works: how it is that these marks and sounds that we make convey meaning to someone else.

Postcard of Mississippi steamboat circa 1909 (collection of Peter Clericuzio / CC BY-SA 3.0)

LOA: What you say makes me think about language both as a tool, something used for political or survival purposes, and also something more ineffable or sublime—the sonorousness of language, for example. Those two things might seem contradictory, but they also might complement or amplify each other.

PE: It can’t work one way without the other. The language works as poetry because of the importance of language in other situations.

LOA: Let’s talk about the relationship between Jim and James and Huck. What allows their bond to exist other than pure necessity? Or is it simply that these two characters are thrown together and forced to be reliant on each other?

PE: Theirs is a friendship. And friendships are complicated and messy, and in true friendships there is a bond which is often not understood.

Certainly in Huck Finn, I think they are thrown together, as characters are in novels. They do have a relationship, in that they know each other, but it’s the circumstances that create the bond. Whereas in James, there are other factors involved that, without ruining anything, contribute to a need on the part of James to stay with Huck and look after him.

LOA: Twain’s novel is called Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and yours is called James. Would you consider James’s story an “adventure,” too? How do you think about that term and its relation to the two texts?

PE: James is a Black man in America; calling it an “adventure” would be redundant. Even the choice of title for Huck Finn, “The Adventures of,” is an articulation of Twain’s desire to make a marketable product. Tom Sawyer was an adventure, and that’s where he made his money.

Illustration of Jim from 1884 edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (E. W. Kemble / Public Domain)

I’ve never understood Huck Finn being—except in the abridged versions—a kids’ book. I think it most strikingly is not a children’s book, and I wonder if that’s where some of the flak around the novel actually comes from in the culture. It’s sad that the presence of the word “nigger” should be enough to have some reactionary folks want to ban the book. But that’s obviously from people who have not read it, and if they have read it, they don’t understand the book and they can’t get past that word. It’s the 1830s United States. Not only was the word used, but it was used freely and with abandon. To not understand the period and the kind of hostility that was just extant on a daily level would be to misrepresent the place, the time, and the lives that were being lived.

LOA: One thing I found so striking in James was the interposition of this other iconic American literary form, the narrative of the escaped slave. There’s a reference to Venture Smith, to William Brown’s manuscript, and James sees himself as writing into that tradition.

PE: Tautologically, that’s exactly what it is, because he’s an escaped slave. But he’s also writing against that tradition, in that he is resistant to the idea that he would have to relate his story through a white vehicle to be heard. It’s important to James that he writes his own story and doesn’t just tell it. That’s where full agency will exist and where he can’t be infantilized by a pernicious white presence.

LOA: Huckleberry Finn is rife with irony, and James similarly takes a very ironic view of the world. There is the simultaneous presence of so much humor but also so much darkness and horror around that humor. How does levity and laughter play against the brutal reality in which these books take place?

PE: I think I’m pathologically ironic, and anything funny I say issues from that perspective. I don’t really write jokes. It’s all situations.

First of all, humor is a disarming tool that allows a writer to put a reader at ease and then do other bad things to him. If you can relax your audience, then the serious stuff will actually have more gravity, because the reader has made a decision that it’s serious instead of having me express to them that it’s serious.

Irony is something that everyone in the world who has been oppressed as a group finds in order to survive the situation. There is so much irony and humor in the death camps during World War II. And Black humor didn’t start with Richard Pryor. Slaves told each other jokes, and more importantly, they told each other jokes that their oppressors could neither hear nor understand. They did this with their own particular sense of irony, expressed with their own particular language.

Really, the most important part of this work is stressing that everything comes back to language—not only our understanding of the world, but our ability to survive it and to rise above it.

Percival Everett is a Distinguished Professor of English at USC. His most recent books include Dr. No (finalist for the NBCC Award for Fiction and winner of the PEN/ Jean Stein Book Award), The Trees (finalist for the Booker Prize and the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction), Telephone (finalist for the Pulitzer Prize), So Much Blue, Erasure, and I Am Not Sidney Poitier. He has received the NBCC Ivan Sandrof Life Achievement Award and The Windham Campbell Prize from Yale University. American Fiction, the feature film based on his novel Erasure, was released in 2023. He lives in Los Angeles with his wife, the writer Danzy Senna, and their children.