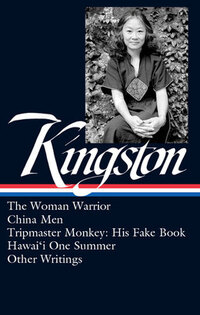

Commentary on the Birds by Jed Munson (Rescue Press, 2023)

For our first Influences column of 2024, essayist and poet (and former Library of America editorial fellow) Jed Munson reflects on how the works of two LOA series-members—Maxine Hong Kingston and Aldo Leopold—influenced his debut essay collection, Commentary on the Birds (Rescue Press, 2023). Exploring the ecology and complex human geography of the Korean Demilitarized Zone through a hybrid of prose and imagery, Munson deftly blends memoir, criticism, poetry, and field notes from his time studying the DMZ as a Fulbright scholar to create a multifarious portrait of this politically and personally contested site.

“As a biracial Korean American, Munson’s navigation route to and from the DMZ on the Korean peninsula is often disjointed and disparate, yet such migratory pattern may be one of many identities and languages of diaspora itself,” writes the poet Don Mee Choi. “Munson has constructed a deeply felt and thought-provoking multi-dimensional diorama of the DMZ—its internal and external geography of pains and mines. This brilliant book can also be read as a field guide to seeking and observing diasporic self and birds.”

Read on for Munson’s reflections on two writers who, for very different reasons, impacted his craft.

Tracing one’s steps, especially where the footprints have disappeared, is one of the motifs around which my essays converge. Everything influences everything, eventually, right? So the question of literary influences has been an especially interesting one to consider in the wake of publishing my collection, which has done multitudes for me personally while, unsurprisingly, doing nothing to resolve the contradictions in my writing. I’m still in the world, on more than one timeline.

I’m about to teach, for the third consecutive semester, Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior. Reading it as an undergraduate, I remember not quite knowing what was happening to me but recognizing something exciting and familiar about the dizziness she made me feel. Sometimes when my extended family comes over it feels like a burglary—emotionally, I’m saying. Possibly a rapture. Similarly, Kingston’s swirling family accounts are so emphatic and exuberant that one feels almost powerless in the current of her prose.

More than anything, I’m drawn to the beautiful bifurcation inside her mother’s voice: it’s at once Kingston’s reproduction, an homage, and a force outside her control. From the book’s opening provocation, the gossip junkie in me sits up: “‘You must not tell anyone,’ my mother said, ‘what I am about to tell you . . . ’”

Throughout The Woman Warrior, the tropes of hearsay, myth, and dreams put pressure on the notion of memory as a private bank or stable palette for the memoirist to draw on. Kingston’s renditions and refractions of memories prove to be the most honest modes available; through literary portraiture, her mother becomes a larger-than-life haunting. The daughter-memoirist’s anxiety about her mother is conflated with the reader’s own slightly morbid anxiety about whether it’s OK to be overhearing (and enjoying) these conversations at all. Of course, these questions are not shortcomings, but one source of the book’s music.

I’m someone who is always seeking ways of addressing legacies in my blood while trying to still honor the variability of my so-called individual person, and The Woman Warrior continues to serve as a model of fearless, adventurous, and wildly awake writing. By fearless, I do not mean mere irreverence or boldness; I mean courage derived from honesty. In my view, the confessional is a crucial valve of Kingston’s instrument; the confessional is a methodical and inquisitive rhetorical mode, not just a spew.

WATCH: Maxine Hong Kingston speaks on Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson at LOA’s 40th anniversary gala reception in 2023

Recognition of love for someone, of desire to know someone—especially someone I may think I already know—is in my experience nearly concurrent, even synonymous, with the recognition of their total unknowability, engendering a reverence for their mystery. An aspect of this paradox, which has been my (non)stance on relationships and writing lately, can productively expand to involve one’s larger social and environmental community—a notion I fatefully encountered almost ten years ago in Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac.

How could Leopold’s outdoors, his rural Wisconsin, be so lovely and expansive? How was his inside so assured? Was his ease of diction deserved? It frustrated me.

As a Wisconsinite, I grew up hearing Leopold’s name in school, but I didn’t read anything by him until I took a course in wildlife ecology as a first-year college student. At the time, my father was mourning the ash trees that had once lined our boulevard. After they were taken out by the emerald ash borer (or, rather, preemptively cut down by the city in anticipation of the bug), I remember wondering if the trees’ fate was natural, if my father’s grief was, if my wondering these kinds of things was.

Leopold’s “land ethic” was a stimulant to my thinking then, an irritant. I struggled with what I perceived as his leisurely descriptions of a yard (it was actually bigger than that, a plot of land) through the changing seasons of a Gregorian calendar year (hence “almanac”): a portrait of privilege tinged with boredom, I couldn’t help but think. The vignettes of each month, clearly mindful as they were, seemed so unafflicted by the pensiveness that plagued my desperate, daily walks as a teenager.

How could Leopold’s outdoors, his rural Wisconsin, be so lovely and expansive? How was his inside so assured? Was his ease of diction deserved? It frustrated me. My landscape, only a county away from his, was bleak, suburban. My fits of prose only seemed to enclose me. And at the same time I was so compelled by Leopold’s serious and dexterous attention, his gentle but firm assertion of idealistic ecological frames in Western philosophical terms: organisms have a “biotic right” to exist; the land as a categorical conception ought to expand to include all the networks of life an ecology entails.

Of course my real frustration with the text was a suspicion that something was being overlooked in what were otherwise persuasive claims. Something erased and so not apparent, one could argue, to a white man on a stroll. It was a problem not with Leopold’s writing or thinking, which is lovely in its humble, methodological approach, but his status as a revered pioneer. Leopold is hailed as the father of wildlife ecology, technically a fine claim, since the field is just a field. But I doubted that he was the first to be awestruck by lightning, to see a goose and see therein the prophet of spring, to look at a row of white pines standing “rank upon rank” in winter, “when the hush of elemental sadness lies heavy upon every living thing” and feel “a curious transfusion of courage.” If even I had had similar stirrings, surely people long before Leopold had conceptualized their inner workings.

Yet originality was never Leopold’s claim or the point: nowhere to my knowledge does the writer say he’s the first to observe or record his Wisconsin habitat. That said, his take on the task has a unique, understated fervor that has not left my mind. I’m certain Leopold didn’t consider his landscape a microcosm of the world, but neither did he view it as fully contained within the world. “Sand County” isn’t fictitious, but neither is there an actual county in Wisconsin by that name. It’s both a nickname and the proposition of a new coalition around forms of attentiveness that writing can mediate. Among many things, Leopold’s “almanac” models attention to connection, insists on it as part of its form. I find myself in regular, urgent need of such an example.

Aldo Leopold in 1942 (Courtesy of the Aldo Leopold Foundation, www.aldoleopold.org)

Jed Munson is the author of the book of essays Commentary on the Birds (Rescue Press, 2023), as well as four chapbooks of poetry, including Minesweeper, winner of the 2022 New Michigan Press/DIAGRAM prize. He was a Fulbright scholar to South Korea in 2021 and a fellow at Library of America in 2022-23. His work can be found in journals such as Full Stop, Conjunctions, Poetry Northwest, and Image, among others.