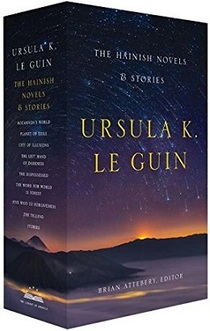

Major works:

The Left Hand of Darkness • The Word for World Is Forest • The Dispossessed • The Earthsea series

Ursula K. Le Guin was born in Berkeley, California, the daughter of a pioneering anthropologist, Alfred L. Kroeber, and a best-selling biographer, Theodora Kroeber. Le Guin’s career as novelist, poet, essayist, translator, and children’s book writer spanned more than half a century, and earned her five Nebulas and five Hugos, among many other awards, and in 2014 she was awarded the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. Her books, whether science fiction, fantasy, or historical fiction, challenge our ideas of what’s natural and inevitable in human relations—and celebrate courage, endurance, risk-taking, and above all, freedom. Best known for her science fiction Hainish novels and stories, which include The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) and The Dispossessed (1974), as well as for her fantasy series Earthsea, her work has influenced a host of modern writers, including Neil Gaiman, Terry Pratchett, David Mitchell, Salman Rushdie, Zadie Smith, and Algis Budrys. Michael Chabon has said that Le Guin’s writing “helped shape my way of thinking about men and women, love and war. She was and remains a central figure for me.”

Malafrena

Ursula K. Le GuinHe left the pleasant dinner party somewhat depressed in spirit. The marchioness had placed several darts in him with exquisite accuracy. She had reminded him that his cause had been defeated time and time again; she had reminded him that the Paludeskars were very curious companions for a revolutionary; she had reminded him of the ambiguity of his own position. And yet she had done all this not, he admitted, in enmity to his cause, but in support of it. She had as good as asked, Where is our revolution? What are you doing about it?

He walked restlessly about his room in the Arrioskar house, then went to the window that overlooked the garden, opened it, and leaned out. The fountain lilted in its stone basin, a thin silvery sound in the night. A fountain at the street crossing a few doors down interwove a faint counterpoint. The wind was down. It was profoundly still, the stillness of the long fields that stretched on from the city on every side. A few stars burned humidly bright in the sky washed blue with moonlight. Beauty, balance, harmony. . . . Sick of himself, Itale tried to lose himself in the moonlight, the quiet, but could not; in this germinant darkness, this moment between March and April, between sleep and wakening, he found only anger, uncertainty, and fear.

Turned back upon himself he tried to face himself, demanding the source of the trouble. When had his work become, not an end, but a mere distraction from—or means toward?—some different and obscurer end? What necessity was he shirking, with what angel must he wrestle? In asking the questions, it seemed to him that the trouble lay in his presence here, now, in this house. All his uncertainties of the last months might clarify themselves if he could simply answer the question, What am I doing here?