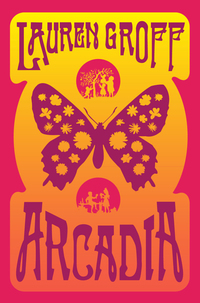

Lauren Groff, who has just published her second novel, Arcadia, joins our continuing series of guest blog posts by writers of fiction, poetry, essays, and history with an appreciation of the “deeply sensual, deeply stunning” writing of James Salter.

Like most passionate readers, I have a private catalogue of favoritehood, a floating list of twenty writers who make me want to genuflect when I think of them. The rules are simple for my secular saints: I have to respect the writer’s entire oeuvre, deeply love a few of her books, and feel as if at least one of the bunch has been written directly upon my heart. Marilynne Robinson is one of my saints, and Housekeeping is the book of hers that is tattooed on the very center of me. Vladimir Nabokov is another, and Speak, Memory is it. Marguerite Duras’s The Lover, George Eliot’s Middlemarch, John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Shirley Hazzard’s The Transit of Venus, Mavis Gallant’s Paris Stories, Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian; there are more, but not so many I couldn’t tell you about them all, if given a few hours. I feel suffused with joy just writing the titles.

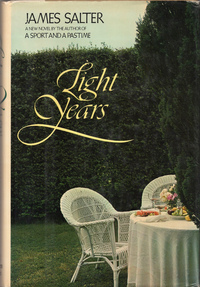

When I say that I love James Salter, then, I mean that I like all of his books, and love Dusk and Other Stories and A Sport and a Pastime. But Light Years, his 1975 novel, glows in a holy way. I buy it in multiples because I press it into the hands of practically everyone who enters my house, and I reread it a few times a year to reset my expectations of what a great novel looks like. Those nights, I stay up alone in the quiet house, hearing my babies’ sleeping breath in the monitors, and open Light Years to let myself feel the beauty, and the ache of sadness that I’m so careful to modulate in my own domestic sphere. To function, I need my ecstatic experiences controlled, limited to the time it takes to read a book. Light Years sits beside me like a good friend during those sleepless nights, and together we watch the morning dawn with its just-bearable brightness.

The description of the book belies its power: Light Years traces the unexceptional marriage of Nedra and Viri, a well-off couple with a house on the Hudson, two little girls, a pony, a bunny, a dog, all the accoutrements of a comfortable bourgeois life. They love each other, have lovers, fall apart. But the true story of Light Years is more mysterious and far colder, found in the way it is told, in brief, vivid scenes strung like pearls on a filament of decades. The book has been called impressionistic, but I think that’s false, because impressionism implies a blurred close-view and a cohesive long-view, and every sentence and scene in Light Years is cut by diamonds. It’s more like a series of careful explosions, strobing one after another through the darkness of years. Or it is a deep river glinting in the sun. Salter at times comments on his project, while ostensibly talking about his characters’ lives. He writes of Nedra and Viri:

Their life is mysterious, it is like a forest; from far off it seems a unity, it can be comprehended, described, but closer it begins to separate, to break into light and shadow, the density blinds one. Within there is no form, only prodigious detail that reaches everywhere: exotic sounds, spills of sunlight, foliage, fallen trees, small beasts that flee at the sound of a twig-snap, insects, silence, flowers.

In his Paris Review interview in 1993, Salter said, “I’m a frotteur, someone who likes to rub words in his hand, to turn them around and feel them, to wonder if that really is the best word possible.” It’s true; Salter’s phrases are deeply sensual, deeply stunning. “We dash the black river, its flats smooth as stone. Not a ship, not a dinghy, not one cry of white,” he writes in his first lines. And later:

She was beautiful, she knew it, her neck, her wide mouth, she felt it as one feels strength. She had been swimming aimlessly, resigned to vanishing in the sea, and suddenly she was at a sunlit meal, the light occasionally gleaming on his glasses.

When the reader is not being tenderized by the sophisticated undercurrents of emotion in this book, she is being seduced by Salter’s language. His dialogue hides more than it reveals; the sudden darts into his characters’ points of view uncover the author’s profound generosity toward them, even when they’re acting terribly. It is this wild generosity that is James Salter’s greatest gift to a reader, the ability to hold within a single character or scene or sentence the precise and the deeply mysterious, the admirable and the dirty, the flesh and the spirit. To look upon it all with clear and warm eye, without judgment or false sentiment. To offer it up in a way as aesthetically devastating as anybody ever has in the history of novels. If such kindness to we hungry, sleepless, aching readers of the world isn’t saintly, I don’t know what is.

Reviewing Lauren Groff’s first novel in The Boston Globe, Karen Campbell wrote, “As The Monsters of Templeton bounds back and forth in time, Willie and her ancestors tell stories rich in history, painful with deceit and misery, and triumphant in salvation.” “I was sorry to see this rich and wonderful novel come to an end,” commented Stephen King, “and there is no higher success than that.” It was a New York Times and Book Sense bestseller. Delicate Edible Birds (2009), a collection of nine stories, followed, which Joanne Wilkinson in Booklist found “richly conceived” and “finely detailed” from “a young writer who continues to surprise.”

Richard Russo describes her new novel as “Richly peopled and ambitious and oh, so lovely, Lauren Groff’s Arcadia is one of the most moving and satisfying novels I’ve read in a long time. It’s not possible to write any better without showing off.”

Groff lives in Gainesville, Florida with her husband and two sons.

The Library of America anthology Into the Blue: American Writing on Aviation and Spaceflight includes an excerpt from James Salter’s novel The Hunters.