In connection with the publication in September 2009 of Thornton Wilder: The Bridge of San Luis Rey and Other Novels 1926–1948, edited by J. D. McClatchy, Rich Kelley conducted this exclusive interview for The Library of America e-Newsletter.

Library of America: You have now edited two Library of America volumes of Thornton Wilder’s works: Thornton Wilder: The Bridge of San Luis Rey and Other Novels 1926–1948 and Thornton Wilder: Collected Plays and Writings on Theater. The new volume collects five of his seven novels, six stories, and four essays. You once wrote that you prefer Wilder’s novels to his plays. Why?

J. D. McClatchy: I realize that, for someone who has worked both sides of the street, declaring a preference for one side isn’t fair. In part, I prefer the novels because they are undervalued. Wilder’s celebrity has always derived mainly from his plays, yet his novels have more amplitude and variety, more cunning and power, and certainly more style than his other work.

But I also prefer them for this reason: I am moved by them—I mean entranced, puzzled, laughing, or close to tears—after reading them again and again. I am moved when I see Our Town, but more on the stage than on the page. Wilder brings all his gifts as a playwright to the writing of novels. I think it’s correct to say he had a dramatic imagination. His novels are obviously written by a theatrically canny author. The way their scenes are composed, the way the characters interact—there is a remarkable intimacy and vividness. But the novels also give Wilder the chance to engage his moral imagination more fully. These novels are exceptionally wise excursions into the motives and desires of a breathtaking array of men and women.

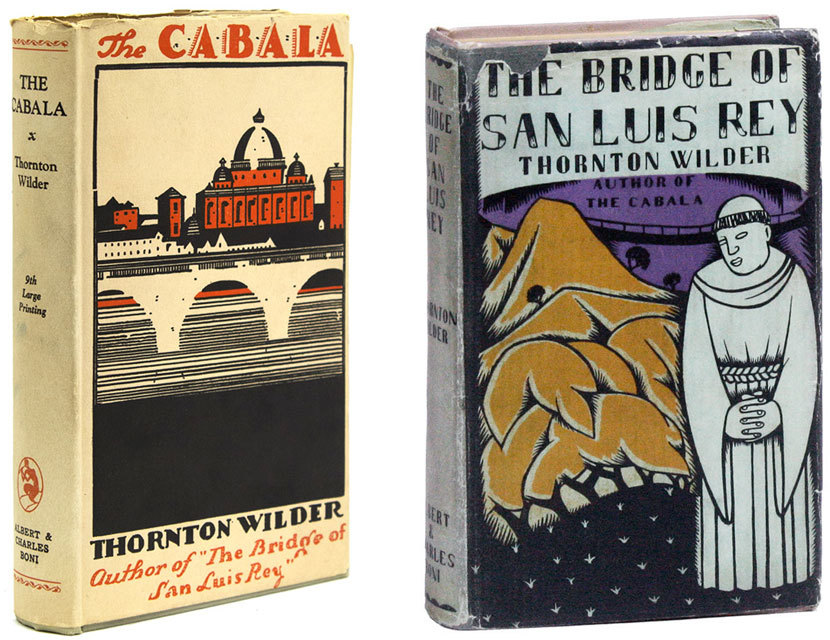

LOA: Wilder enjoyed success from his first published effort. The New York Times hailed his first novel, The Cabala, written when he was 29, as “a magnificent literary event” and “the debut of a new stylist.” Does that acclaim stand the test of time?

McClatchy: It does, though—in the wake of High Modernism and the wackier excesses of Postmodernism—“style” is no longer the measure by which a novel is judged. (Alas.) But when The Cabala appeared in 1926, the literary scene was dominated by heavy social realism or by fluff. (That year’s best-selling novel was Sorrell and Son by Warwick Deeping.) And though today Wilder’s stylization may seem retro, in its day it was both enameled and spiky. Its polish was bright, its irony pointed. Waugh’s Decline and Fall, say, was still two years in the future. Wilder’s style in The Cabala is much closer to Hemingway’s than to anything older, stuffier. (The Sun Also Rises was published this same year.) Its modernism may not be apparent today, but when you consider its collage-like construction, its precise and lean phrasing, his interest in historical pastiche (even, dare I say, deconstructivist pastiche), his dramatization of repressed feelings, and much else that literary scholars will be exploring, it’s a safe call to place The Cabala among the best novels of its time. And it reads marvelously today. It was the book of Wilder’s that first made me sit up straight in my reading chair. It was— and remains—whole, surprising, elegant . . . delicious. From the start, Wilder was a natural stylist, with an instinct for both epigram and architecture, a writer for whom the heart is a baroque court and the mind a classical academy.

LOA: Wilder published his second novel, The Bridge of San Luis Rey, just a year later and it won the Pulitzer Prize while he was still teaching French at Lawrenceville. That must have been quite a heady event for such a young writer. How did the Pulitzer change his life?

McClatchy: Prizes change a writer’s public life, not his private tasks. The notoriety results in increased sales, requests to give lectures, a better publishing deal the next time around . . . and gives newspaper obituary writers a headline for the column-on-file. Wilder’s reaction? He went on a hike in the Alps. I think that, in general, Wilder knew his worth and didn’t much care for the tin medals.

LOA: The Bridge of San Luis Rey has become the prototype for the modern “disaster story” in which the lives of the characters involved in a catastrophic event are examined through flashbacks. Do you think our familiarity with the form diminishes our appreciation for what he achieves here?

McClatchy: About a year after The Bridge came out Wilder wrote to a friend: “It seems to me that my books are about: what is the worst thing that the world can do to you, and what are the last resources one has to oppose it. In other words: when a human being is made to bear more than human beings can bear—what then? . . . The Bridge asked the question whether the intention that lies behind love was sufficient to justify the desperation of living.” That kind of inquiry transcends genre or period. What makes The Bridge the enduring novel it is has everything to do with the questions it poses about our purpose on Earth. It starts out as a book about the truth, and ends up as a book about love. Both of those can be “disasters,” yet we have nothing else to live by.

LOA: Five of the six stories collected here date from before Wilder’s first novel. What criteria did you use in selecting which stories to include?

McClatchy: I tried to pick the strongest examples of his apprentice work. I left out a couple of stories that were weaker or repetitious. Most writers, of course, would pay to have their earliest work destroyed, but readers are fascinated by an author’s early efforts. In Wilder’s case, it’s fascinating to watch him experiment with ironic situations and sophisticated dialogue. Just like the plays he was writing as a Yale undergraduate, these early stories show him becoming himself.

LOA: Wilder seems to have been conflicted about writing novels. Your chronology notes that in 1935, after he had published three novels, he vowed to abandon fiction because he believed the omniscient narrator was “out of gear with twentieth-century life.” Harry Levin once wrote that “he was more in his element as a dramatist than as a novelist.” Yet he went on to write four more novels. Did he work his way out of his dilemma?

McClatchy: Well, that was a remark made to reporters when he disembarked from a transatlantic crossing. One has to say something! But also, it was in the months before that remark that he had started work on what would a few years later become Our Town. The idea had taken powerful hold of his imagination, and it’s no wonder he was temporarily distracted from the novel. He knew he didn’t have to choose between being one sort of writer or another. Each required a different cast of mind, but drew on the same imagination.

LOA: The Cabala is set in Rome. Wilder based his third novel, The Woman of Andros, on the Roman playwright Terence’s Andria. His fifth novel, The Ides of March, tells the story of Caesar’s assassination through the letters of Catullus, Cicero, Cleopatra, and Caesar. Whence this obsession with Roman culture?

McClatchy: All his life, of course, Wilder had a scholar’s curiosity. He was a voracious reader, and even in his seventies he was boning up on advances in microbiology, studying Greek vase painting and the theories of Claude Lévi-Strauss. But that initial trip to Rome in 1920 and his stay at the American Academy there had a profound impact. He later wrote: “For a while in Rome I lived among archeologists, and ever since I find myself occasionally looking at the things around me as an archeologist will look at them a thousand years hence.” He was drawn to the historical novel in part, I think, because of its exotic appeal (how different everything was!) and eerie relevance (how much the same everything has always been!). I think, too, the Roman character appealed to his own: its stoicism, its discipline.

LOA: The Woman of Andros is set in pre-Christian Greece yet seems to argue that so-called pagan culture had realized, in the person of the Andrian woman, a courtesan, many of the values of Christianity. This theme of universal human values—outside religion—runs through many of Wilder’s works, novels and plays. Was this his great theme?

McClatchy: One of them, to be sure. “I am not interested,” he told an interviewer, “in the ephemeral—such subjects as the adulteries of dentists. I am interested in those things that repeat and repeat and repeat in the lives of the millions.” He meant, of course, the mysteries and marvels of the heart. Wilder once described Tolstoy as “a great eye, above the roof, above the town, above the planet, from which nothing is hid.” Wilder might as well have been describing his own talents as a novelist. He looked on life steadily, never blinking at its pain and incongruities. Whether it’s the broad picaresque comedy of Heaven’s My Destination or the philosophical poise of The Ides of March, he kept his writing, in the words of a journal entry of his, “lyrical, diaphanous and tender.” I have always thought of Wilder as one of a special category of artists—Jane Austen, Ivan Turgenev, Jean Renoir, and Elizabeth Bishop are among them too—whose work refreshes our intelligence and deepens our understanding.

LOA: Wilder won three Pulitzers, one for The Bridge, one for the play Our Town ten years later, and one for The Skin of Our Teeth in 1943. Throughout his writing career he was actively teaching either high school or university students. How did Wilder view himself? As a novelist, a playwright, or a teacher?

McClatchy: As I think I’ve been hinting all along, he was that rare writer—playwright, novelist, and teacher in one. The characters in his plays have the quirkiness and depth of characters in novels; you feel you’ve known them forever and are implicated in their fates. His novels have the immediacy and intensity of plays; the lives of characters unfold slowly and unexpectedly before your eyes. And everywhere, he balances lives, ambitions, desires, and sorrows in a moral scale. The best kind of teacher is the one who asks the right kind of questions. Is there a better example of that anywhere than The Bridge of San Luis Rey?

LOA: Two of the four essays in the book concern James Joyce. Wilder had a lifelong fascination with Joyce and with Finnegans Wake in particular yet none of his novels seems very Joycean. Edmund Wilson wrote in 1928 that Wilder was “the first American novelist who has been influenced deeply by Proust.” Which writers did influence Wilder’s writing?

McClatchy: As a schoolboy he read Shakespeare, Dickens, Henry James, and Walter Scott. As a novice writer, he read Proust, Flaubert, Saint-Simon, and Madame de Sévigné. He was always drawn to the German classics, and to the theater of many cultures. It’s clear he had studied Noh drama, Spanish tragedy, as well as Austrian farce. He had an astounding capacity to absorb the lessons of the masters, and it’s said he was a mesmerizing teacher at the University of Chicago, where one day he would be lecturing on Don Quixote and the next day on Molière. He was obsessed with Joyce and fascinated by Stein, but neither, as you say, had a direct influence on his own writing. Myself, I think Wilder was fortunate in that regard.

LOA: Heaven’s My Destination—a comic romp following a traveling salesman through Depression-era America—was quite a departure from Wilder’s other novels. Henry Seidel Canby said it was what Voltaire would have written “if he had been sent to Hollywood and going by bus through Illinois and Kansas had tried his hand at Candide rewritten in terms of the farm belt, the Bible, a closed mind and a well-intentioned heart.” Was this Wilder’s response to Michael Gold’s slashing attack on The Woman of Andros in The New Republic as “a daydream of homosexual figures in graceful gowns moving archaically among the lilies?”

McClatchy: Michael Gold’s attack on Wilder as an effete writer out of touch with his own country was particularly mean-spirited, and meant to cause hurt. In private Wilder’s feelings were bruised—whose would not be?—but he refused to respond in kind. Clearly, though, Heaven’s My Destination was written in reaction to Gold’s diatribe. It is his first distinctly “American” novel. It sets itself down in the Mississippi Valley and points west during the Depression, offers an array of social types, analyzes their living conditions and legal system, and probes both the country’s beliefs and its true religion, business. It was enough to warm any Marxist’s heart. In a letter to John Dos Passos, Edmund Wilson wrote: “Thornton Wilder has taken up the challenge flung down by Mike Gold and written the best book of his life.”

It would be inaccurate to claim that Wilder had deliberately remade himself as a novelist––had gone native. (Though Our Town arrives just three years later.) The settings and characters of Heaven’s My Destination bear subtle affinities with Wilder’s other fiction, both earlier and later. And its hero, George Brush, shares the ardent loneliness of all of Wilder’s protagonists.

But it is fair to say that Wilder did turn from the exquisite cadences and lambent, layered textures of his first three novels. His style here is drier, flatter, jumpier. It’s the effort to create an “American speech” for his book, to give its narrative the clipped, moral tone of its cast and culture. It’s what might be called a Grant Wood style. Of course Wilder was not writing a satire, though he’s content to skewer pretensions and injustices. Instead, he’d set out to write a comedy, and he needed a light touch to capture the incongruities of American life, at once innocent and egotistical. It is a comedy in the highest sense, and moves easily from Corn Belt farce to superstitious magic (Father Pasziewski’s spoon) to moral argument (the concluding courtroom scene is the book’s masterstroke).

LOA: Unrequited love recurs as a theme in The Cabala, Bridge, and The Woman of Andros. While Wilder never made his sexual preference explicit during his lifetime, do you think that lines like “And at once he sacrificed everything to it, if it can be said we ever sacrifice anything save what we know we can never attain, or what some secret wisdom tells us it would be uncomfortable or saddening to possess” from The Bridge give us a clue?

McClatchy: I think Wilder’s sexual desires were largely a mystery to him—and they certainly are to us. He seems to have been baffled by his own homosexual desires and ashamed of his furtive attempts to act on them. As you suggest, that may very well have given him a sharper sense of exclusion, disappointment, and secrecy than other novelists have had. Sex and Sensibility . . . an endlessly intriguing and elusive connection.

*LOA:*_How did you first become involved with the work of Thornton Wilder? Did you discover new things about his work in putting the new volume together?_

McClatchy: I started reading Wilder’s novels in high school—The Bridge and The Ides of March. The others came later, as did my appreciation of those two familiar novels. This parallels the fate of Our Town: you first encounter it when you are old enough to be touched by it but still too young to understand its depths. And later you realize it is not the sentimental chestnut you’d remembered, but a dark, wrenching, overpowering work about human memory and loss. So too with these first five novels of his. Encountering them again, having oneself acquired the scars on the heart Wilder had set out to reveal, you feel you are at last reading them for the first time, in all their true freshness and wonder and gravity. I sit stunned, time and again, by their shimmer and tensile strength, their miraculous access to the soul’s secrets.