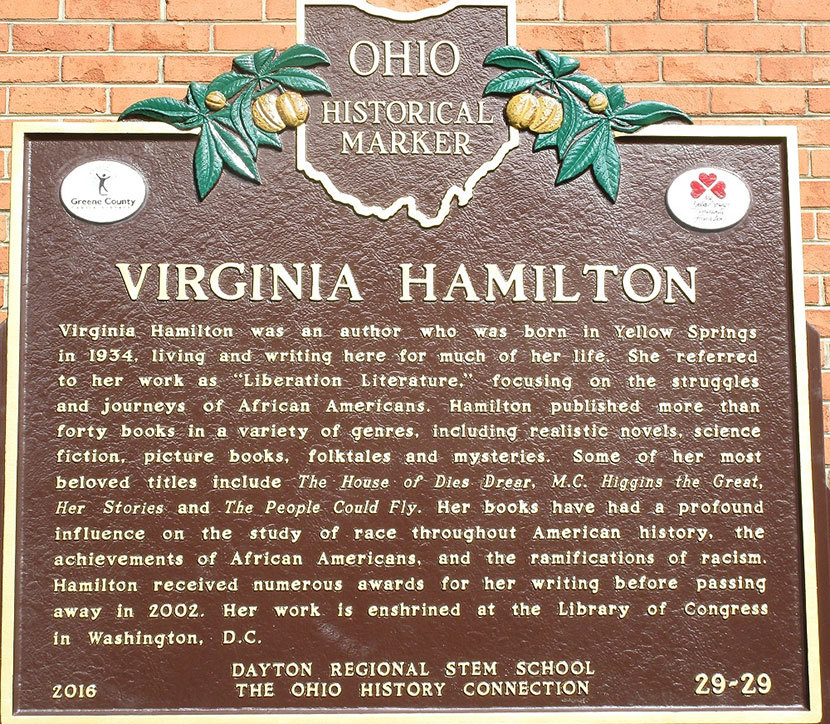

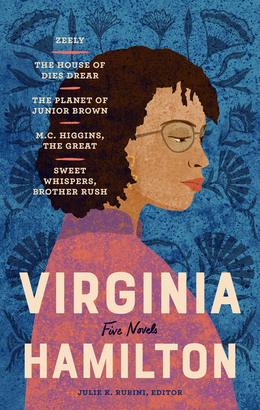

A multiple-award-winning twentieth-century writer makes her Library of America series debut with Virginia Hamilton: Five Novels, which gathers together five celebrated books—Zeely; The House of Dies Drear; The Planet of Junior Brown; M.C. Higgins, the Great; and Sweet Whispers, Brother Rush—that initially appeared between 1967 and 1982 and were foundational in establishing a multicultural children’s literature in the United States.

Reviewing Virginia Hamilton: Five Novels for the Wall Street Journal, Meghan Cox Gurdon said that it “reminds us why she was so lauded and provides a wonderful excuse, if one were needed, to revisit her striking prose and singular vision.”

The new volume’s editor is Julie K. Rubini, author of a biography for young readers, Virginia Hamilton: America’s Storyteller (Ohio University Press, 2017), which received a Kirkus starred review and was listed on Bank Street College of Education’s Best Children’s Books, Outstanding Merit. Rubini is also the founder of Claire’s Day, an Ohio children’s book festival held each year in honor of her late daughter.

Over Zoom, Rubini spoke with Library of America about the sources of Hamilton’s creativity, the traits that made her a groundbreaking author, and her timeless appeal. This conversation has been edited for clarity and concision.

Library of America: Who was Virginia Hamilton, and why is she important?

Julie K. Rubini: Virginia Hamilton is the most honored author of children’s literature ever. She was born and raised in Yellow Springs, Ohio, among family who told stories that flew around her like fireflies in the Yellow Springs summer nights. She often said that her writings were a combination of memories and re-creations of all the elements that her family passed on verbally in stories. And yet Hamilton didn’t have that gift—to share those stories orally. So at a young age she began writing them down in a notebook.

Sadly, she lost the notebook and, as her husband Arnold Adoff shared, mourned that loss of her earliest writings for the rest of her days.

Virginia continued to write and eventually attended Antioch College on scholarship. She studied writing there for three years. A professor at Antioch suggested she study under a professor at Ohio State University. That writing instructor felt Virginia was ready to move forward as a writer and suggested that if she truly wanted to be published, as one did back in the mid- to late-’50s, that she move to New York City. So she moved to New York and began her writing journey. Ultimately, Virginia was the author of forty-one works for children and adults that we know and love today.

LOA: What were some of those stories that were passed on in her family that became important to her work?

Rubini: The original story, as she says, is the story of her grandfather, Levi Perry. Levi’s mother, Mary Cloud, escaped from slavery in Virginia and brought Levi to family in the Yellow Springs area, and then disappeared mysteriously, never to be seen again. But Levi was raised in the safety and the warmth of family and would sit down his ten children (including Hamilton’s mother, Etta Belle) every year and tell them that in saving him his mother saved the rest of them, perhaps changing their lives and ultimately letting them know that they were free—and freedom was never to be taken for granted.

Grandfather Levi, who was instrumental in Hamilton’s early life, would share this original story, and from there they would tell stories about aunts and uncles doing crazy things—like her Aunt Leah, who was so worked up when Orson Welles broadcast War of the Worlds that she was outside for hours on end with her shotgun shooting anything in sight. Another uncle caught some bank robbers in the act, chased them into a well, and apparently fell into the well after them.

How many of these stories are true or how many are “re-memory,” as she called them? These fantastical stories created a thread throughout her childhood that stirred her imagination and helped her become the storyteller that we know.

LOA: Can you tell us about the five books in the collection?

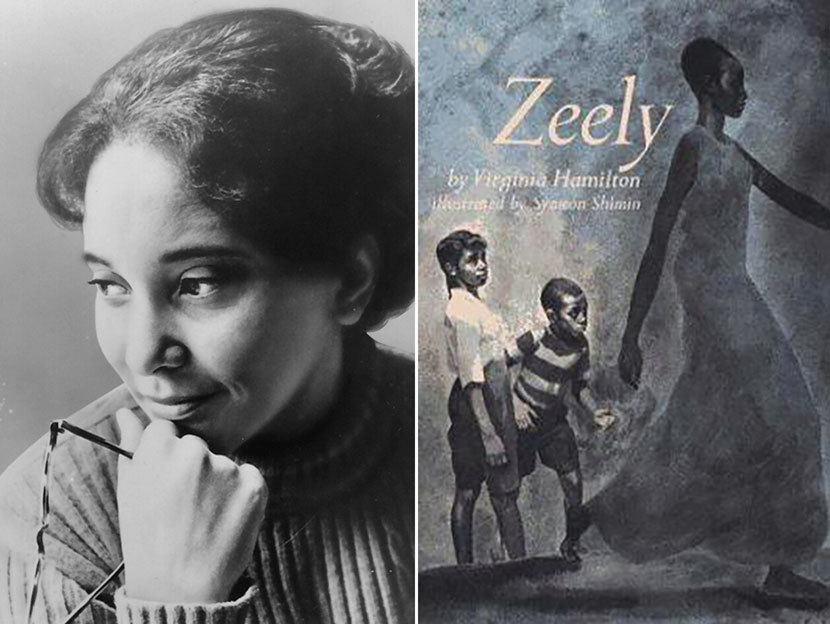

Rubini: The first is Zeely, her first published work. Originally it was a short story that she was working on at Antioch, where she had befriended a woman named Janet Schutz who went on to work for Macmillan, in New York City. When Hamilton moved to New York, Janet suggested that this story could be a children’s story. Hamilton was also working on a novel for adults; she never envisioned herself as being an author of children’s works, and there’s a great interview with her on YouTube where she admits that she didn’t really understand the complexities or the structure of children’s books. But she figured it out quickly and obviously did quite well with it.

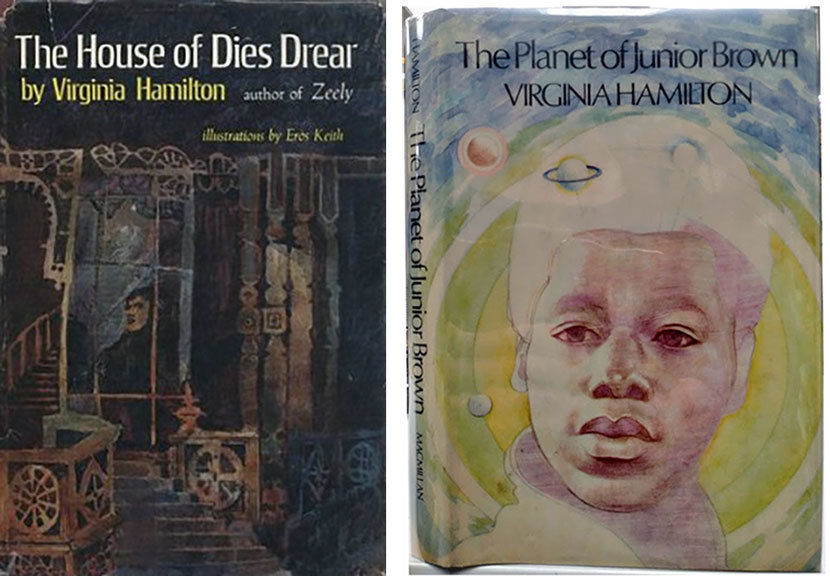

Zeely was followed by The House of Dies Drear, which was one of Arnold’s favorites because he loved mysteries. The home that serves as the story’s setting is inspired by one that was actually part of the Underground Railroad. Then we have The Planet of Junior Brown, the story of a homeless boy. It is really an incredible, unusual tale, one that sheds light on situations that are occurring today where we have so many homeless children.

My personal favorite is M.C. Higgins, The Great. While conducting my research for my biography of Hamilton, I discovered a story of her sitting in editor Susan Hirschman’s office, telling Hirschman that she had the image in her head of a boy with lettuce leaves wrapped around his wrists. Hirschman said, you just need to follow this boy and the story will reveal itself. That became the story of M.C., whose family lives on Sarah’s Mountain, which is to be his family home but is being strip mined. So there’s the concern of whether this mountain will remain, and what it will be like: themes of wanting to remain where you are, at home, and yet the promise of maybe a better life somewhere else.

And then we have Sweet Whispers, Brother Rush, which, as I offered, touches on death. There’s a ghost. You can see a trajectory in Hamilton’s writings where it had been more middle grade as far as themes and characters and then with Sweet Whispers, Brother Rush she delves into deeper subjects and for an older audience. The collection reflects her growth as a writer and the depth in which she explores various themes.

LOA: What’s in these novels for adult readers?

Rubini: Hamilton is such a fantastic storyteller that it’s hard to put her stories down.

But these novels center on the themes that are prevalent in all her works: families and love and challenges, and conflicts and mystery and so many subjects that are still relevant to us as adult readers. Particularly with Sweet Whispers, Brother Rush, the themes of death and grief that are addressed there are ones we can learn from as adults. The same goes for the empathy we have with her characters.

For all the realism and all the magic in her stories, the work is much deeper than it seems at first glance. As I worked with the Library of America in putting together this collection, I discovered new messages and imagery that I hadn’t the first time around, when I was writing her biography.

LOA: How does the world of children’s literature look different after Hamilton than it did before?

Rubini: From my awareness and reading of Hamilton’s works and understanding what types of work there were before she came along, her writing voice was so unique and complex that it opened avenues for authors and readers alike to explore themes and situations and stories unlike any there had ever been before. Virginia referred to her work as “liberation literature.”

She changed the landscape in creating an awareness of African American characters and families and bringing an understanding of the fact that we all want the same things in our stories even though our characters may look different. That’s as important today as it was yesterday.

She was the first African American, male or female, to win the Newbery Medal, in 1975. The fact that that it didn’t happen before then is in some degree sad, but you see the trajectory as far as the awareness and recognition of these significant Black authors and illustrators for children’s work today. Hamilton paved the way.

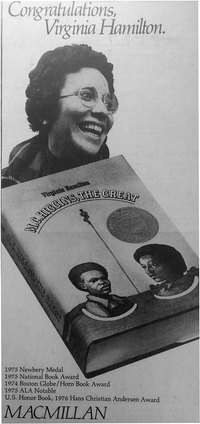

Her work has been recognized through every major award for children’s literature, from the Newbery Medal, the National Book Award, the Boston Globe-Horn Book Award (all three for M.C. Higgins, the Great), the International Hans Christian Andersen Medal for her body of work, multiple Coretta Scott King Awards, and the MacArthur Fellowship (the “genius grant”).

LOA: Can you talk about Hamilton’s partnership with Arnold?

Rubini: On school visits, when children ask me, what did I enjoy most about telling Hamilton’s story? I would answer that the love, that partnership between Virginia and Arnold, is my favorite part of her story.

Here was a young woman in New York City, working several jobs, trying to make her way, and still writing, with the ultimate goal of getting published, and then meeting Arnold in New York City. Sometimes she would borrow money from him, and it was just a friendly relationship until one night at the Five Spot Café, where Charlie Mingus was playing (Arnold was Charlie’s manager). Hamilton came in and amid the sounds of the cool jazz bouncing off the roof and Charlie working away at his bass, she saw Arnold in a different light than she had before. Charlie offered Arnold a ride home and in turn Arnold offered Virginia a ride home and then quietly asked for her phone number. As I share in my biography of Hamilton, back then it wasn’t as easy, phone numbers were a series of digits and letters, so Arnold was trying to remember Hamilton’s phone number all the way home because he didn’t have pen and paper, and all the while Charlie was talking to him.

Arnold got home and called Hamilton right away. And they talked nearly all night long. He said that during that conversation, while he was reading poetry to her and they were exchanging stories, he realized he needed to spend the rest of his life with her. Their love story began at a time (1960) when there were over twenty states where it was still illegal for a Black person to marry a white person. Even in their relationship, as a Black woman from Yellow Springs, Ohio, and a white Jewish man from the Bronx, they paved the way for others.

Ultimately Arnold became her agent, and made some groundbreaking moves as far as being with multiple publishers, which really wasn’t something that was done back then. Even today, authors will align themselves with an editor and a publisher and won’t venture to other publishers for other works. Arnold helped that process happen with Virginia because he was such a staunch supporter of her work. He was quite an accomplished poet himself (and author and teacher), but there wasn’t any power struggle—he just believed in her work.

It was ever so sad when we lost Arnold this last year because he was indeed a great friend. I’m sad that he didn’t live to see this collection, which he supported and was proud of.

LOA: How does Virginia Hamilton’s legacy live on?

It lives on through her incredible body of work, through the Virginia Hamilton Conference on Multicultural Literature for Youth, held annually at Kent State University, and, most importantly, through the many educators I’ve met over the years who continue to teach and share Virginia’s work in their classrooms. Just as those fireflies continue to swirl every summer in Yellow Springs, so too do Hamilton’s stories swirl in the imagination of young readers.

LOA: Is there anything else that you’d like to add?

Rubini: When I first met Arnold, he took me to Hamilton’s gravestone. It reflects what she was very proud of, which was the many labels that she wore. To the outside world she was the incredible author of a variety of works, and she would present herself in her speeches as comfortable and confident, and yet she was a very shy person. She preferred nothing more than to be sitting in her office, working away on her manuscripts and, even more, spending time with Arnold, and even more perhaps than that, being with her children.

They had a daughter, Leah, and a son, Jamie. Their reflections depict Hamilton as a mother who would drop everything in a heartbeat to take Leah to soccer practice or help Jamie get to a band recital. She was incredibly supportive and loving as a mom and a very loving and kind person. I think that it’s important to know Virginia as an author, but just as important to know her as the incredible human being that she was.

At the beginning of Chapter 10 of my biography, I quote her words:

For children, reading is the discovery of new worlds of color and texture. For me, writing for children is the creation of worlds of darkness and light. There is an essential line between us, a line of thoughts and ultimately of communication. Each book must speak: “This is what I have to say,” in the hope that each reader will answer: “That is what I wanted to know.”

I think that summarizes Virginia and her work perfectly.