Constance Fenimore Woolson (1840–1894)

From Constance Fenimore Woolson: Collected Stories

When the name Constance Fenimore Woolson comes up in literary conversation (and to our way of thinking, it doesn’t come up nearly often enough), she is usually mentioned in the same breath as such writers as Henry James, George Eliot, Sarah Orne Jewett, or even her great uncle James Fenimore Cooper. What might surprise modern readers is that when her stories began appearing in national magazines, many (and perhaps most) critics compared her to Bret Harte, the Californian author famous for such Western stories as “The Outcasts of Poker Flat.”

When Woolson decided to become a full-time writer, she purposefully chose subjects and locales that would distinguish herself from the “sentimental” female authors scorned by most male critics. Thus, inspired by Harte’s fiction set in the frontier of California’s gold country, she wrote stories about the residents of the lumber and trapping camps on the Great Lakes islands, where she had spent her summers as a child, or the remote rural communities of Ohio, where she vacationed as a young woman, or the exotic new resort town of St. Augustine, Florida, where she wintered in the 1870s.

One of the more popular of her early stories, “The Lady of Little Fishing,” is basically a rewrite of (and response to) “The Luck of Roaring Camp,” the story that made Bret Harte famous. While Harte imagined what might happen when an infant boy is stranded among the gruff, filthy men of a mining outpost, Woolson adapted the idea by introducing a lone woman, rather than a baby, into an all-male camp on an island in the Great Lakes region. Like the infant, the “lady” radically changes the men—but not necessarily for the better.

We present “The Lady of Little Fishing” as our Story of the Week selection, with an introduction that examines more fully the links between the careers and stories of Harte and Woolson.

Read “The Lady of Little Fishing” by Constance Fenimore Woolson

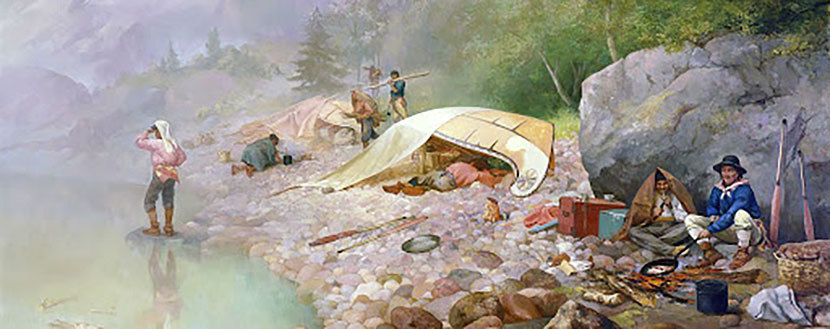

Image, above:

From 1858 to 1870, Frances Anne Hopkins lived in Québec with her husband, a Hudson’s Bay Company administrator soon promoted to superintendent of the Montréal department, and she accompanied him on many of his journeys to HBC stations, expeditions that took them as far as Thunder Bay on Lake Superior’s northern shore and Marquette in upper Michigan. Like the Lady in Woolson’s story, she was often the only woman at an outpost, and she made sketches of trappers, traders, and voyageurs—the French Canadian boatmen who transported furs. She transformed many of these drawings into paintings after she and her husband returned to London in 1870.