Exactly one hundred years ago today, U.S. Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby certified documentation making the Nineteenth Amendment part of the Constitution — thereby guaranteeing American women the right to vote.

Library of America commemorates the anniversary with its latest anthology, American Women’s Suffrage: Voices from the Long Struggle for the Vote 1776–1965 which recounts, through ninety pieces by over seventy writers, the campaign for women’s suffrage in all its diversity.

Earlier this month, the book’s editor, historian and biographer Susan Ware, shared some insights into her selection process for American Women’s Suffrage. In the special guest blog post below, she expands on the earlier interview with further thoughts on the significance of this month’s centennial.

By Susan Ware

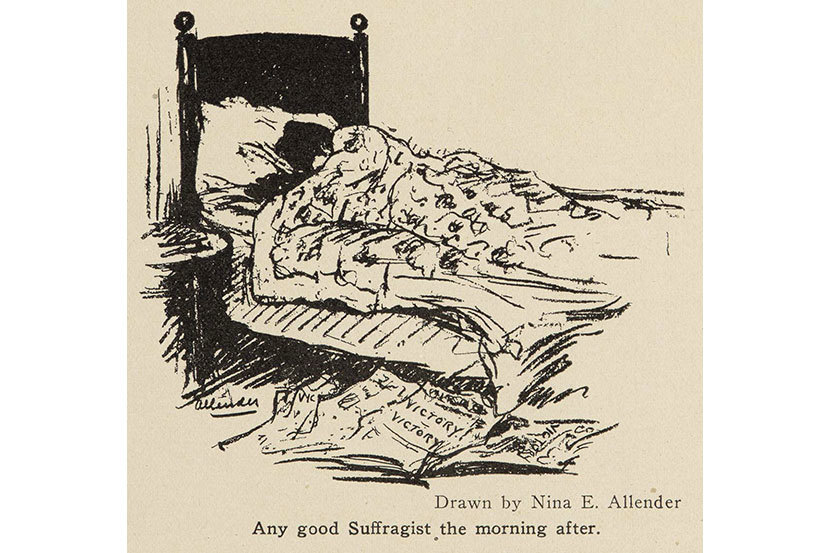

One of my favorite suffrage cartoons is that of an exhausted suffragist fast asleep under a comforter, surrounded by newspapers proclaiming victory littering the floor. The creator, Nina Allender, captioned the cartoon “Any good Suffragist the morning after.” After all the events I have been doing leading up to the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment on August 26, 2020, I will probably want to roll over and go back to sleep the morning after too. But like the suffragists, I will rouse myself from under the covers and get back to work. There is still much to do.

Journalist Emma Bugbee observed, as women prepared to go to the polls for the first time after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, “There are about twenty-six million women voters, but no woman voter. Much less is there a woman vote.” Women collectively won the vote, but they exercised that right as individuals. Then and now women are far too diverse a group to function as single-issue voters solely on the basis of sex.

But it is wrong to conclude that suffrage did not matter or that women beat a hasty retreat from politics after 1920. Rather than remaining united around a single goal like the vote, politically engaged women embraced a wide variety of causes in the postsuffrage era. A similar insight applies to antisuffragists once the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified. No matter where they stood on the political spectrum, women were saying forcefully, “We have come to stay.”

Women had to learn how to be voters, which was the rationale behind the founding of the League of Women Voters in 1920. It was not always easy for newly enfranchised women to march confidently into polling places, which may help to explain why only one-third of eligible women voters went to the polls in the 1920 presidential election. The proportion of eligible women who voted rose steadily from then on, and by 1980 it exceeded the proportion of eligible men, as it has in every presidential election since. Even if women don’t vote as a bloc, politicians ignore women voters at their peril.

When assessing the impact of the Nineteenth Amendment, it is always important to look at the big picture and remember that change does not happen overnight. Rather than positioning 1920 as the end of the story, it is far more fruitful to see it as initiating the next stage in the history of women’s political activism, a story that is still unfolding. If we think of suffragists as the voting rights activists of their day, we see how the suffrage movement fits into this larger story.

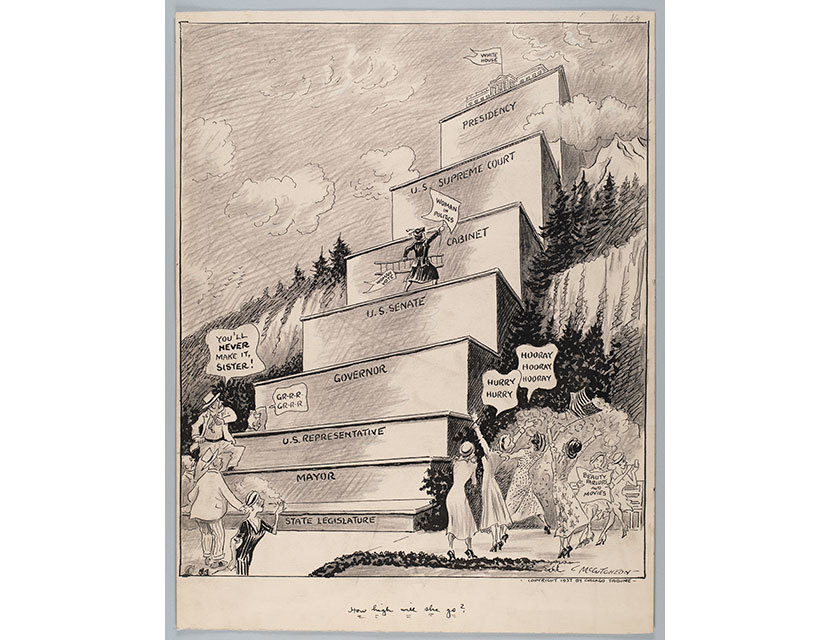

Despite the political energy that suffragists devoted to winning the vote, getting women elected to office was not a high priority at first. Yet it was a logical next step, as political cartoonist John T. McCutcheon depicted in a 1922 cartoon in the Chicago Tribune captioned “How high will she go?” The above version from 1937 features a slightly different set of steps, but both renditions build from local and state officeholding to the White House as the ultimate goal for women in politics.

One hundred years after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, the goal of a woman president remains unfulfilled, although 2020 features Kamala Harris on the Democratic ticket as Joe Biden’s running mate. Even though women candidates continue to be subjected to stereotypes and discrimination that limit their acceptance (as Harris will no doubt find out), there is no question that the political climate has changed for the better. The results for the 2018 election were especially striking: 106 women in the House of Representatives and 25 women in the Senate, one-quarter of the upper chamber. Those numbers were a definite improvement over the 19 serving in 1960, and the 5 in 1928, but still far from gender equity. As a political scientist sagely pointed out after the 2018 election, “We are not going to see, in one cycle, an end to the underrepresentation of women in American politics that we’ve seen for 250 years. . . . This is a marathon, not a sprint.”

Why does the Nineteenth Amendment matter? The women’s suffrage movement stands out as one of the most significant and wide-ranging moments of political mobilization in all of American history. By the early twentieth century, women had already moved far beyond the domestic sphere, yet a fundamental responsibility of citizenship was still arbitrarily denied to half the population. The Nineteenth Amendment changed that increasingly untenable situation, representing a breakthrough for American women as well as a major step forward for American democracy, producing the largest one-time increase in voters ever. Three generations of women honed their political skills in the women’s suffrage movement, and those skills were put to good use after the vote was won. In their new roles as women citizens, women made a difference, which is another way of saying that women’s history matters.

| EDITED BY SUSAN WARE |

|

| American Women’s Suffrage: Voices from the Long Struggle for the Vote 1776–1965 |

Historian Anne Firor Scott provided an especially evocative image of how winning the vote was part of larger changes in women’s lives and in American society more broadly: “Suffrage was a tributary flowing into the rich and turbulent river of American social development. That river is enriched by the waters of each tributary, but with the passage of time it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish the special contributions of any one of the tributaries.” Think of the contributions of individual suffragists, as well as the speeches, articles, cartoons, handbills and fliers they left behind, as the tributaries that make up suffrage history. Each distinctive element flows into the larger stream, creating something stronger and more powerful than the individual voices. And then think of suffrage history as a powerful strand in the larger stream of U.S. history, which is richer and stronger because it heeded Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s prescient statement at Seneca Falls that it is a self-evident truth that all men and women are created equal.

The United States still lacks truly universal suffrage, but the Nineteenth Amendment represented a giant step towards that goal. Whenever you exercise your right to vote, remember that you are standing on the shoulders of the suffragists.

Susan Ware is the author of Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote, American Women’s History: A Very Short Introduction, and Letter to the World: Seven Women Who Shaped the American Century, among other books. She is Honorary Women’s Suffrage Centennial Historian at the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, and General Editor of American National Biography. Her commentary is featured in The Vote, this year’s multipart PBS American Experience documentary on the suffrage movement.