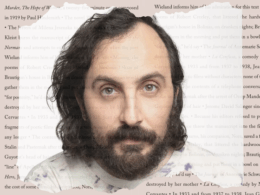

Our latest Influences post by a contemporary writer comes from Chicago-based Ling Ma, whose debut novel, Severance, is published this week by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

“The End begins before you are even aware of it,” begins Severance, and readers soon learn the reason for the novel’s emphatic capital letters. When a modern-day plague decimates New York City, millennial office worker Candace Chen is left to fend for herself in the hollowed-out metropolis before she joins a band of survivors who hope to start a new society in a midwestern refuge they call The Facility. In Ma’s hands, this post-apocalyptic scenario is just the starting point for a satiric vision that takes in late capitalism, the immigrant experience, and the anomie of early adulthood.

Recommending Severance on the New Yorker website, Emily Witt hails “a mix of humor and pathos that reminded me a little of _Infinite Jest and a little of George Saunders,” and on Twitter novelist J. Robert Lennon called it “a corker. Dry, spare, haunting, and weirdly comic.”

In the following guest post, Ma discusses the inspiration she has found in two very different American writers.

William Maxwell, So Long, See You Tomorrow. This narrative takes a strange, magical form. It starts out as a first-person memoir about Maxwell’s childhood in Lincoln, Illinois, then somewhere in the middle of a later chapter decides to transform itself into a novel. But there’s no “trick” to this transformation. “The reader will have to do a certain amount of imagining,” Maxwell writes. He simply tells you exactly where the change occurs as it occurs. And even after we cross into this fictional territory, the transition happens so seamlessly that the narrative doesn’t lose any of its power. Despite the slim look of this book, and despite what some might characterize as Maxwell’s conservative prose and slow pacing, I found it audacious, confident, and urgent.

I first read So Long, See You Tomorrow for a college course on nonfiction writing (one that I was so unprepared for that I eventually had to withdraw), but this book has always stayed with me. We are all haunted by our pasts, and we circle around them, trying to figure out what happened—but ultimately, we are constrained by the limitations of memory. In this book, Maxwell breaks beyond these limitations. He utilizes fiction to inhabit the past more deeply. And I wonder if this isn’t what all fiction writers are doing, in some sense—attempting to re-inhabit our experiences more fully, even as those experiences warp and become something else in the fictionalizing. That Maxwell does this in such a direct, transparent way raises the hairs on the back of my neck. He’s giving away the trade and it doesn’t even matter.

Bret Easton Ellis, Lunar Park. The closest contemporary counterpart I can think of to So Long, See You Tomorrow is Bret Easton Ellis’s Lunar Park. It’s a 2005 novel that initially masquerades as an autobiography before shifting form into a supernatural thriller. The narrators of both break the fourth wall to appeal to the reader. Warning of ominous things to come, Ellis warns: “Regardless of how horrible the events described here might seem, there’s one thing you must remember as you hold this book in your hands: all of it really happened, every word is true.”

The first chapter gives us a seemingly straightforward rundown of Bret Easton Ellis’s life, most of which seems aligned with the Wikipedia version: His SoCal upbringing with an abusive father, the quick ascent to literary fame during the ’80s, his party reputation. After his father’s death, Ellis moves in with his ex-girlfriend (a fictitious Hollywood star, Jayne Martin) and her children in the suburbs. At which point, strange occurrences take place in Jayne’s house. The furniture rearranges itself. A tombstone bearing Bret’s father’s name is found in the backyard. A serial killer, whose murders seem styled after those in American Psycho, is on the loose. A Furby-like toy comes to life. A cream-colored Mercedes 450 SL, the same make and model of his father’s car, speeds through the neighborhood. In short, Ellis literalizes how he is haunted by his past, in the guise of a haunted-house story.

I bought a copy of Lunar Park on a whim at the San Francisco airport. I was revisiting the Bay Area, where I used to live, under the guise of research for a novel, but really, I liked being in the Bay and derived assurance that everything was still where it used to be: the same coffee places, the same grocery stores. My Airbnb was located on the next block from my old apartment, which was still occupied by my ex-boyfriend. I liked to walk through the Mission, especially down this particular street, bisected by palm trees, that I used to see in my dreams after leaving the Bay. So I walked around there too. At some point, I felt like a specter haunting a past I had left behind.

As a writer, I often ask myself this question: Does it have to be fiction? If I’m going to go the route of fiction, then it has to do something that nonfiction isn’t able to do. Otherwise, why invest in creating all this fictitious scaffolding? I’ve found that, at its best, fiction is able to confront our nightmares more directly, as in Lunar Park. It can also inhabit fantasies more viscerally, such as the wish to revisit and live in the inaccessible past, as in So Long, See You Tomorrow. In short, it can do what we lack the ability to do in our own lives.

Ling Ma was born in Sanming, China, and grew up in Utah, Nebraska, and Kansas. She attended the University of Chicago and received an MFA from Cornell University. Her writing has been published in Granta, VICE, and the Chicago Reader, and an excerpt from Severance won the 2015 Graywolf SLS Prize, which Graywolf Press awards annually to the best novel excerpt from an emerging writer. Ma lives in Chicago.